Gothic Survival

The Gothic Revival in America began in 1788 with the building of the second Trinity Church in New York City (figure 2). However there are a few gothic churches that survive from earlier times. These are considered Gothic Survival rather than Gothic Revival because they were part of an architectural tradition surviving from the middle ages. The earliest and best example of Gothic Survival in America is St. Luke’s Smithfield, VA built sometime after 1632. It contains a large traceried window, wall buttresses on its side, and a tower. It also has a Flemish crow-stepped gable not associated with Gothic architecture, but popularized by Dutch settlers. Another example of Gothic Survival is Yeocomico Church VA (1706), which contains a south porch entrance attached to its side, decorated with a rudimentary gothic trefoil. South porches of this kind were ubiquitous in English medieval parish church architecture where they frequently housed baptismal fonts.

Drawings of the lost 1698 Trinity Church in New Amsterdam (now NYC) show a Gothic Survival structure with an eastern apse, a pinnacled tower, and traceried windows. Although this building was destroyed by a fire in 1776, its original gothic style likely influenced the decision to rebuild it in the new Gothic Revival style.

Gothick

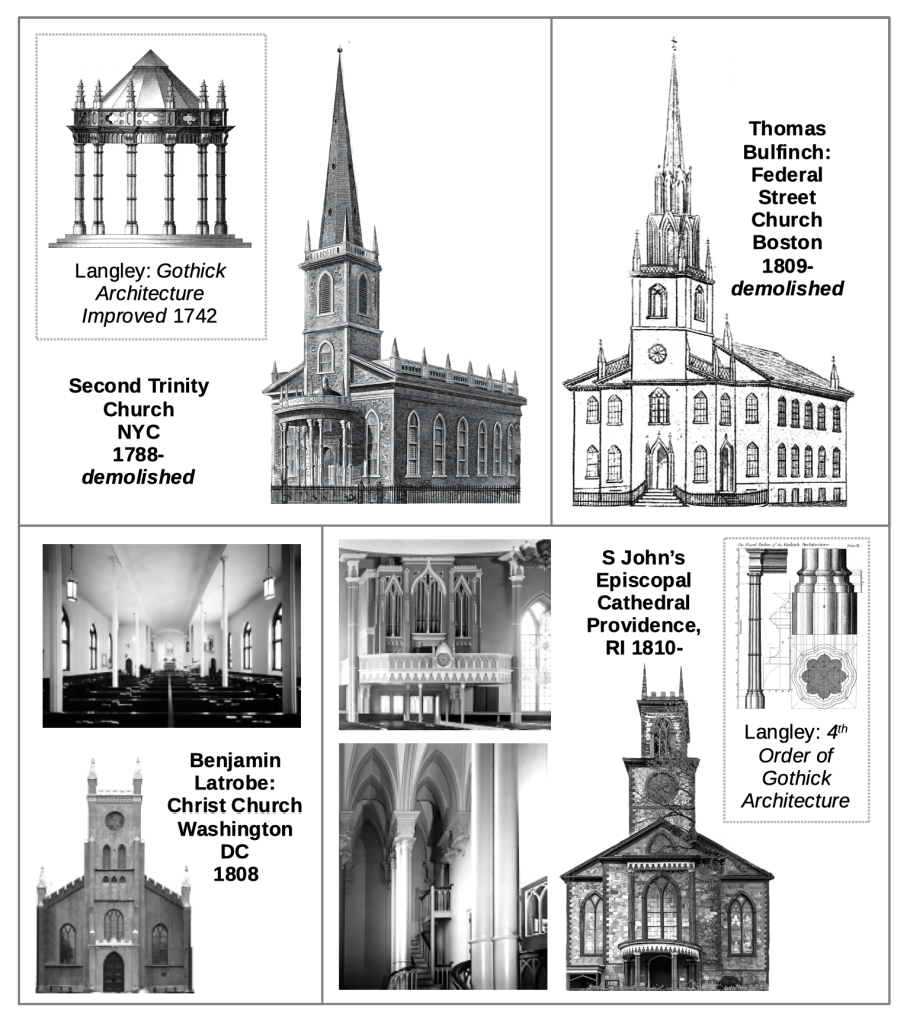

Late 18th and early 19th century Gothic architecture is often called “Gothick” to distinguish it from the more academically correct Gothic Revival style of the mid-19th century. Gothick motifs were popularized in pattern books written by an English architect named Batty Langley (1696-1751), who recommended the Gothick style for auxiliary structures like garden gazebos (figure 2). The architect of the Second Trinity Church (1788) used Langley’s gazebo illustration as the model for the portico.

America’s first two great architects, Thomas Bulfinch and Benjamin Latrobe both dabbled in the gothick style. Bulfinch’s Federal Street Church Boston (1809) is a prototypical steepled meeting house which substitutes the usual classical details for gothick ones. Latrobe’s Christ Church in Washington DC (1808) adheres to a similar meeting house plan but adds castellated elements such as crenellations and a heavily buttressed tower.

St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral in Providence (1810) contains a wealth of gothick motifs, including Langley’s gazebo/portico first seen at Trinity Church. St. John’s interior contains columns and entablatures taken directly from the “Fourth Order of Gothick Architecture,” which was Langley’s attempt to classify Gothic motifs into a series of orders similar to the classifications of Greek and Roman columns and capitals.

Neoclassical Gothic

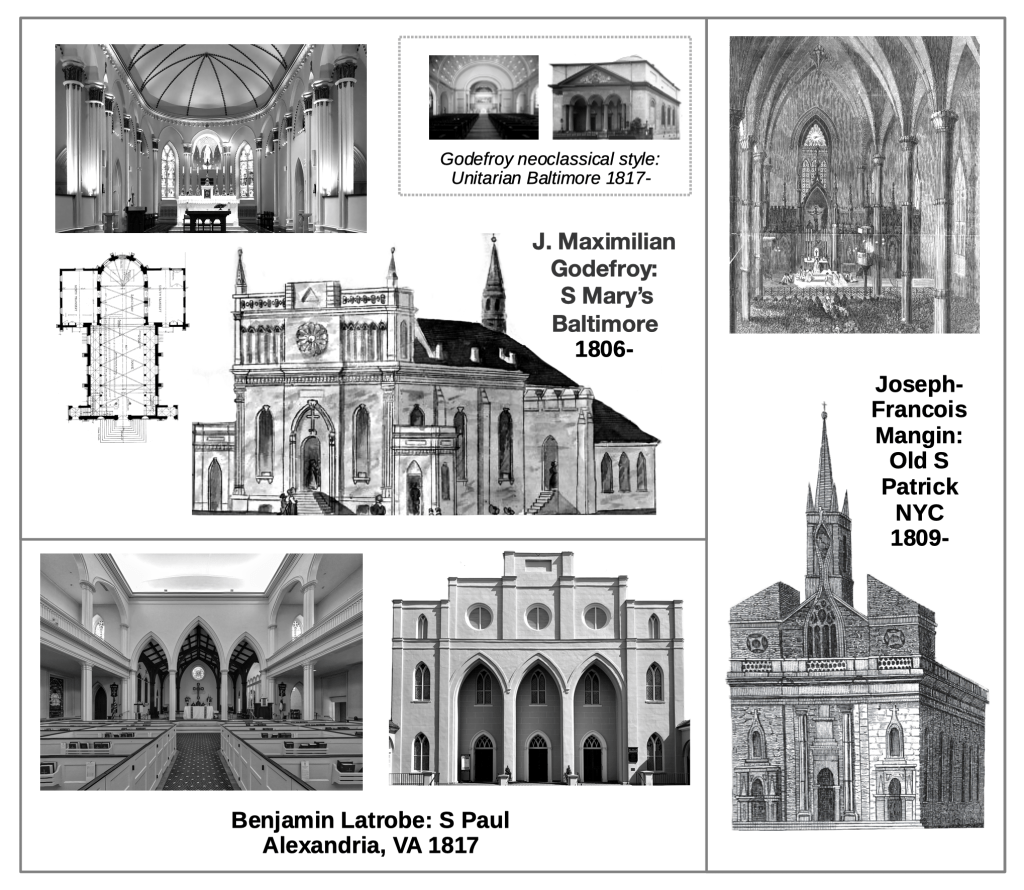

In the early 19th century, American architects began experimenting with a new, more monumental style of architecture called “neoclassical.” J. Maximilian Godefroy’s Unitarian Church in Baltimore, inspired by the Roman Pantheon, is a typical example. Godefroy applied this neoclassical aesthetic to St. Mary’s in Baltimore, only with gothic detailing. St. Mary’s includes an attic story set over a tripartite entrance, an arrangement derived from Roman triumphal arches. St. Paul’s Alexandria (1817) and Old St. Patrick’s NYC (1809) also contain triumphal arch arrangements in their facades.

Castellated Gothic

Castle-like designs with crenelations and pinnacled towers were typical of the early 19th century Gothic Revival, as seen in the examples of the churches and masonic halls from Boston and Philadelphia (figure 4). Two of the finest examples in the castellated gothic style are the Old New York University Chapel (1835-) and Dwight Hall Chapel at Yale (1842). These buildings were important precursors to the Collegiate Gothic style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Old NYU Chapel was inspired by King’s College Cambridge (1446-) and featured an elaborate arrangement of pendant vaults inspired by the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court Palace (1530s). Tragically, this chapel was demolished in 1894. However, its architect Ithiel Town designed another important gothic church that still survives, and which gives us a taste of what the interior of NYU chapel looked like.

Ithiel Town

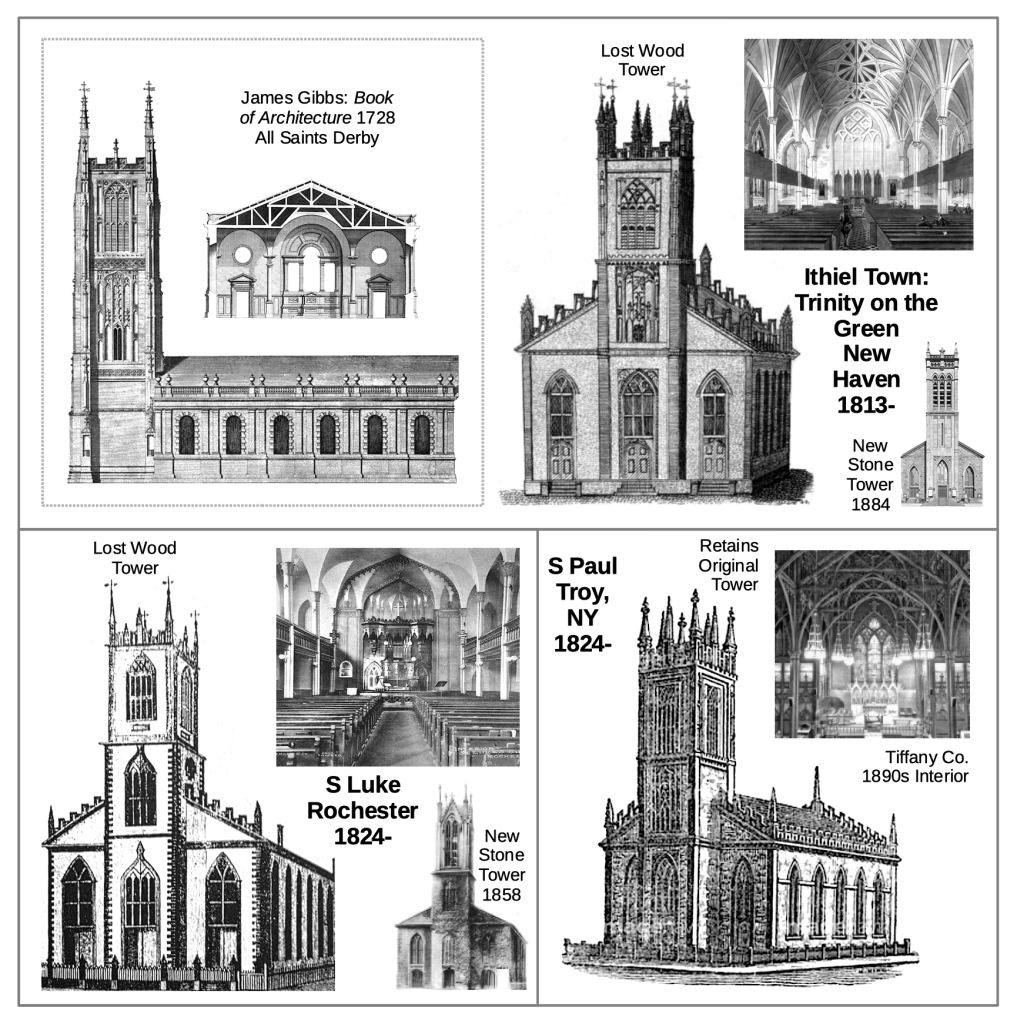

Ithiel Town’s Trinity Church on the Green in New Haven (1813-) marks an important turning point in the American Gothic Revival. Its tower was modeled on an actual Gothic structure built in the 1530s: All Saint’s Cathedral in Derbyshire, England. James Gibbs’ 1728 Book of Architecture contained a drawing of this tower as part of an illustration showcasing his classical renovation of the attached nave. The interior of Trinity Church is a gothicized version of Gibb’s classical nave, with elaborate wood paneling used to evoke gothic ribs. The original flat paneled ribs at Trinity have since been replaced with rounded ribs, but the interior still gives us an idea of what Ithiel Town’s lost chapel at NYU might have looked like, albeit without the pendant vaults.

Unfortunately, Trinity’s tower was made of wood and was replaced in 1884 with a stone tower in a completely different design. However, a stone version modeled on Trinity’s original tower survives at St. Paul’s in Troy NY (1824). St. Paul’s gives us an idea of what the exterior Trinity on the Green originally looked like, providing a link between the medieval gothic of All Saint’s Darbyshire and the American Gothic Revival. (St. Paul’s interior was famously remodeled by the Tiffany Company in the 1890s and remains the best surviving example of the Tiffany Company’s ornate style of interior decoration.)

St. Paul’s Troy was only one of many churches inspired by Trinity on the Green. St. Luke’s in Rochester is another notable copy, although its original wood tower has also been replaced. However it retains much of its original interior.

Richard Upjohn

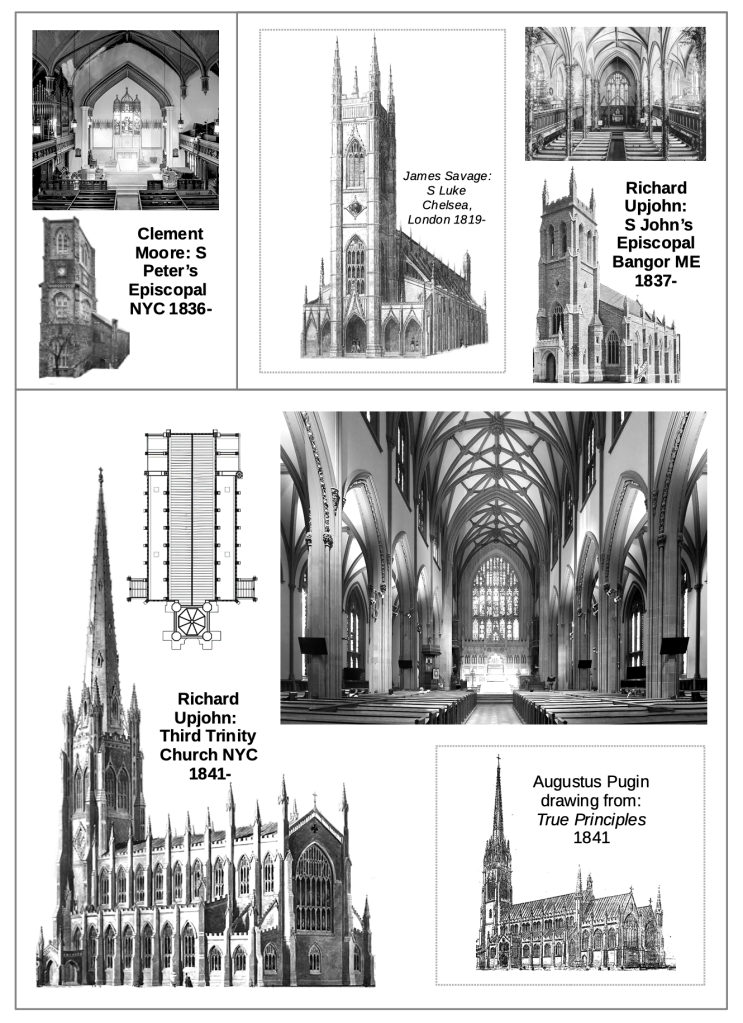

Amateur New York architect Clement Moore designed S. Peter’s (1836), a buttressed towered church informed by a study of real medieval churches. It marks the beginning of a more authentic stage of the Gothic Revival, although it’s interior still adhered to the Ithiel Town meeting house model, with a pendant vault similar to the one from the lost NYU Chapel (figure 4).

This new stage of the revival had previously started in England in 1819, when English architect James Savage introduced a more authentically Gothic floor plan at St. Luke’s Chelsea in London. It was the first Gothic Revival church to contain a nave with side aisles and a clerestory. Richard Upjohn, a young English architect, was most certainly aware of the importance of James Savage’s work at St. Luke’s. After Upjohn immigrated to the United States, he designed St. John’s in Bangor, ME (1837-) which, like St. Luke’s, was a gothic basilica with an aisled nave, albeit without the clerestory. However, St. John’s was even more convincingly Gothic than St. Luke’s. Upjohn added a beautifully designed set of stone buttresses surrounding the front tower, replacing the less-effective octagonal pinnacles surrounding St. Luke’s tower. The success of St. John’s brought Upjohn to the attention of the Episcopal authorities in New York, who hired him to design the third version of Trinity Church.

This third Trinity Church in New York (1841-) surpassed anything yet built during the American Gothic Revival. In part, it seems to have taken inspiration from a drawing published by the famous English gothicist Augustus Pugin in 1841. Like Pugin’s drawing, Trinity contained a space designated as a chancel at its east end. This chancel was defined by aisles of lower height and elevated on a raised floor. This was revolutionary for church architecture in the United States which had always rejected chancels as too “popish.” But times were changing and in the 19th century both Catholics and Protestants were rediscovering the beauty of medieval forms of liturgical worship.

Originally, Trinity Church was designed with a timber framed roof, rather than a faux stone vault made of wood and plaster. Upjohn disliked the idea of faux vaults. In this respect he was influenced by Pugin’s writings, and his advocacy of “authentic” gothic architecture. However he was forced to concede to the religious authorities in New York, who admired faux vaults like the fabulous one at New York University Chapel (figure 4). After Trinity, Upjohn never built another faux vault, opting instead for wooden framed roofs inspired by English parish prototypes.

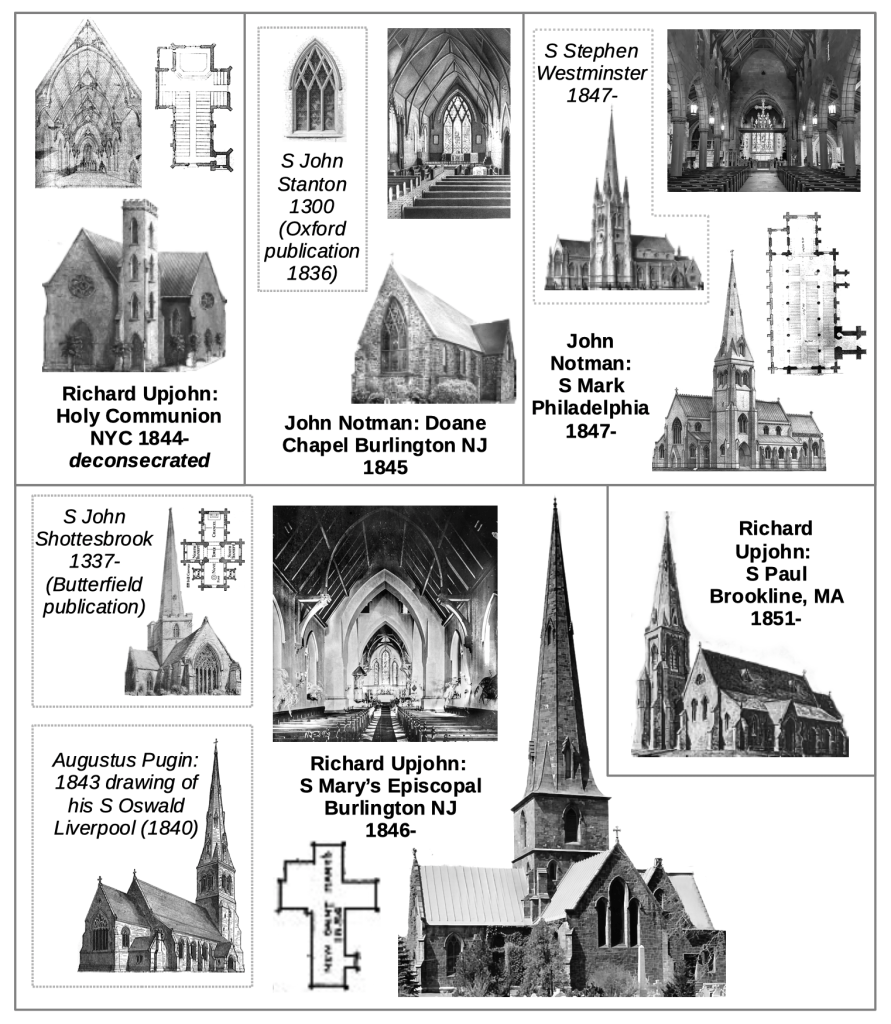

Cruciform and Asymmetrical Plans

The earliest American example of an authentic gothic wood roof was Upjohn’s Holy Communion Church (1844-). This roof has unfortunately been lost in repeated remodels, but another early wood framed roof designed by John Notman can be seen at the Doane School Chapel in Burlington NJ (1845). This chapel also contains a direct copy of a window from St. John Stanton in Oxfordshire (c. 1300), a drawing which had been published in 1836 by John Henry Parker. The Doane School Chapel, along with Holy Communion both contain the first cruciform floor plans of the American Gothic Revival.

In 1847, Notman designed St. Mark’s Philadelphia, which took Upjohn’s aisled-Trinity model and made it even more authentic by giving it a wooden roof and an unplastered, hammer-dressed stone wall. The chancel was deepened and separated from the nave by a rood screen, another ecclesiastically correct motif. As at Upjohn’s Holy Communion, Notman also added an asymmetrically attached tower, a design influenced by drawings he had seen of St. Stephen’s Westminster, which was currently being built. Asymmetrical plans soon proliferated.

Richard Upjohn’s St. Mary Burlington (1846-) highlights the increasing debt Gothic Revival architects owed to authentic medieval models, in this case, St. John’s Shottesbrook (1337-). In 1844, English Architect William Butterfield published detailed drawings of St. John’s which came into the possession of Upjohn. St. Mary takes its cruciform plan with crossing tower from St. John’s as well as many of its details such as the moldings of its doors, windows, and arcades. However, Upjohn also modified the design, lengthening the nave significantly, and substituting the castellated tower and spire for a “hooded” spire introduced by Pugin in his drawing of St. Oswald Liverpool (1840). Both Upjohn and Notman used this hooded-style spire at St. Mark’s Philadelphia, and St. Paul’s Brookline.

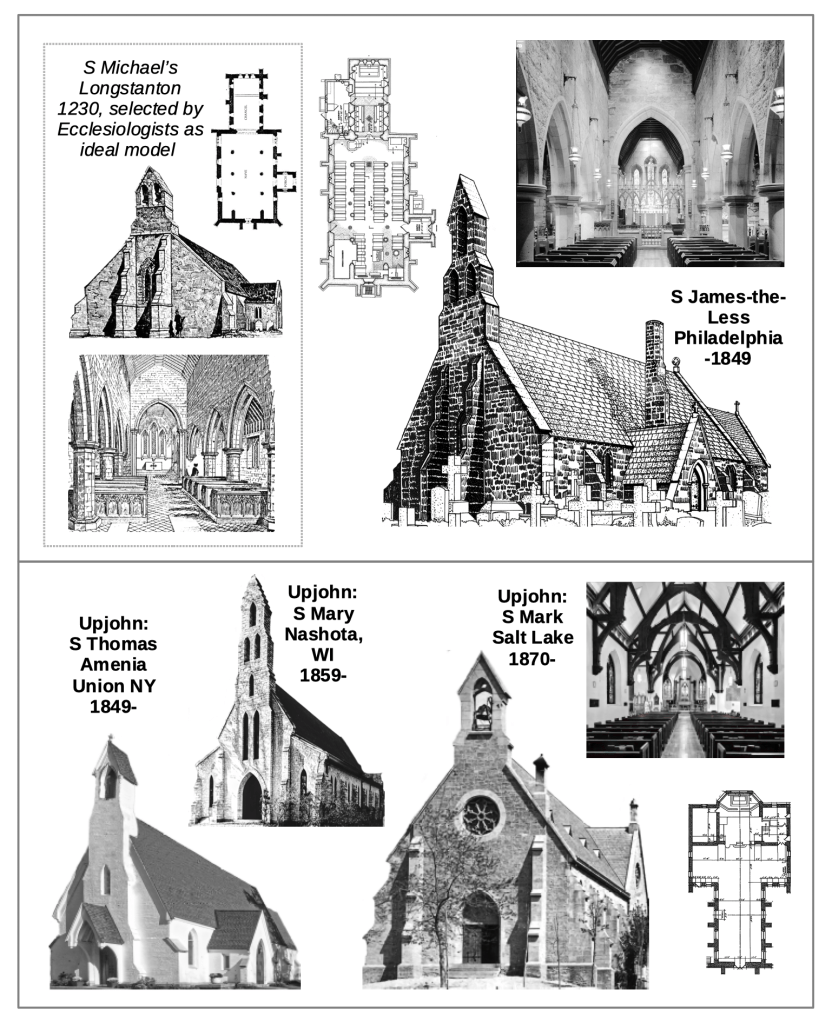

The Ecclesiologist’s Bell Cote Model

The increasing popularity of ecclesiastically correct religious architecture was sped along by a group of liturgical activists called The Ecclesiologists. They introduced an ideal parish church modeled on St. Michael’s Longstanton, Cambridgeshire (1230). This church was replicated at St. James-the-Less in Philadelphia (-1849). It featured a facade with a flat bell cote, a south portal, an arcaded nave with a steep wooden roof, side aisles, and a deep chancel separated by a prominent rood screen. Architects like Upjohn promoted the bell cote model throughout the United States. At St. Thomas Amenia Union (1849-), Upjohn created a brick version. At S. Mary Nashota (1859) he augmented the bell cote with a beautifully proportioned set of attentional arcades. The simplified, aisle-less example at St. Mark’s Salt Lake (1870) highlights the beauty of Upjohn’s hammer beamed roofs.

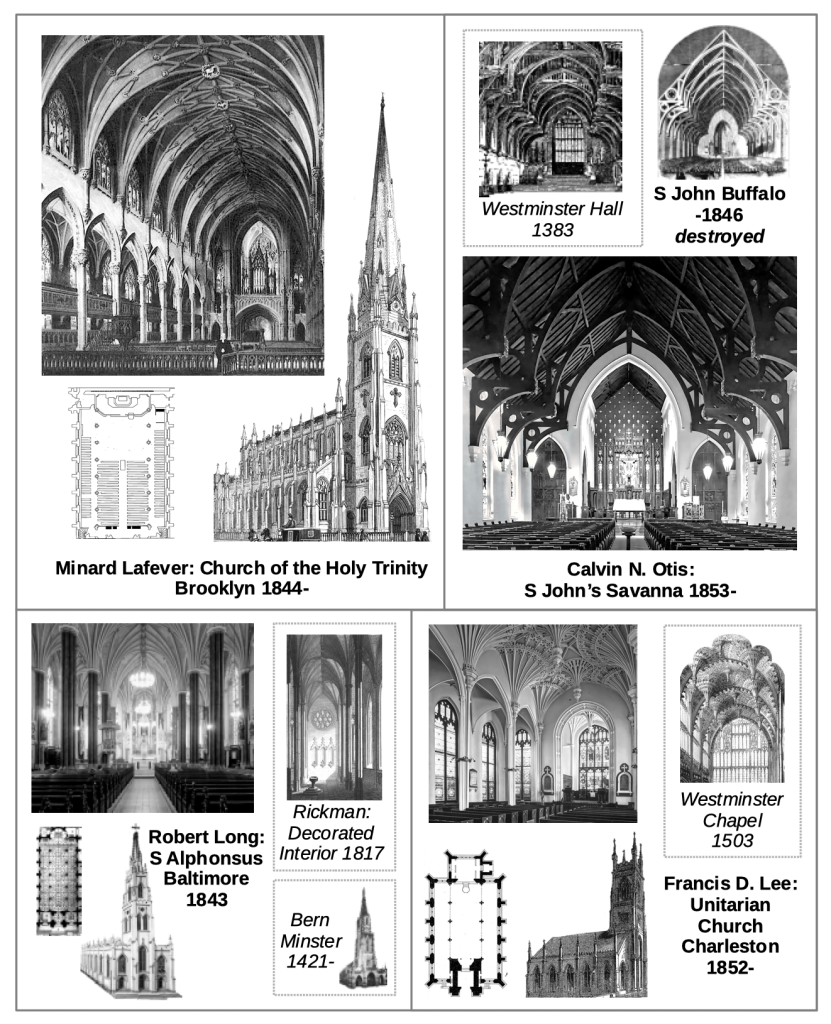

Midcentury Vaulting

Outside of the ecclesiastically correct architecture of Upjohn and Notman, architects like Minard LaFever were building ever more elaborate faux vaults, as seen at Holy Trinity Brooklyn (1844-). Most fantastic of all these faux vaults was Francis D. Lee’s pendant fan vault at the Unitarian Church of Charleston, modeled on Westminster Chapel (1503). In spite of its liberal Unitarian theology, this church also contained a chancel, showcasing just how deeply the Ecclesiologists influence had penetrated into Protestant America.

Architect Robert Long drew on German models for St. Alphonsus’ Baltimore (1843), perhaps Bern Minster or Old Trinity Leipzig, with their highly decorated ogee arched windows and spiky spires. He also built a German “hall type” interior, with aisles the same height as the nave. However, his vault seems to have been taken from an illustration in Thomas Rickman’s 1817 landmark treatise on historic English Gothic styles. St. Alphonsus adheres to Rickman’s description of the “Decorated” style. Long’s interior had the most beautiful vault yet designed in the United States. He defended his use of plaster vaults by noting that, unlike Upjohn’s Trinity, his church had no faux exterior buttresses, making his vaults theoretically valid. His defense was a sign that structural honesty was a growing preoccupation for mid-century Gothic Revival architects.

In 1846, Calvin N. Otis built an elaborate hammer beam roof at St. John’s Buffalo, inspired by the famed Westminster Hall of 1383. This church was unfortunately lost in a fire. However an early hammer beamed hall of this type survives at St. John’s Savanna (1853-). Hammer beamed halls were soon popping up at churches and universities throughout the United States.

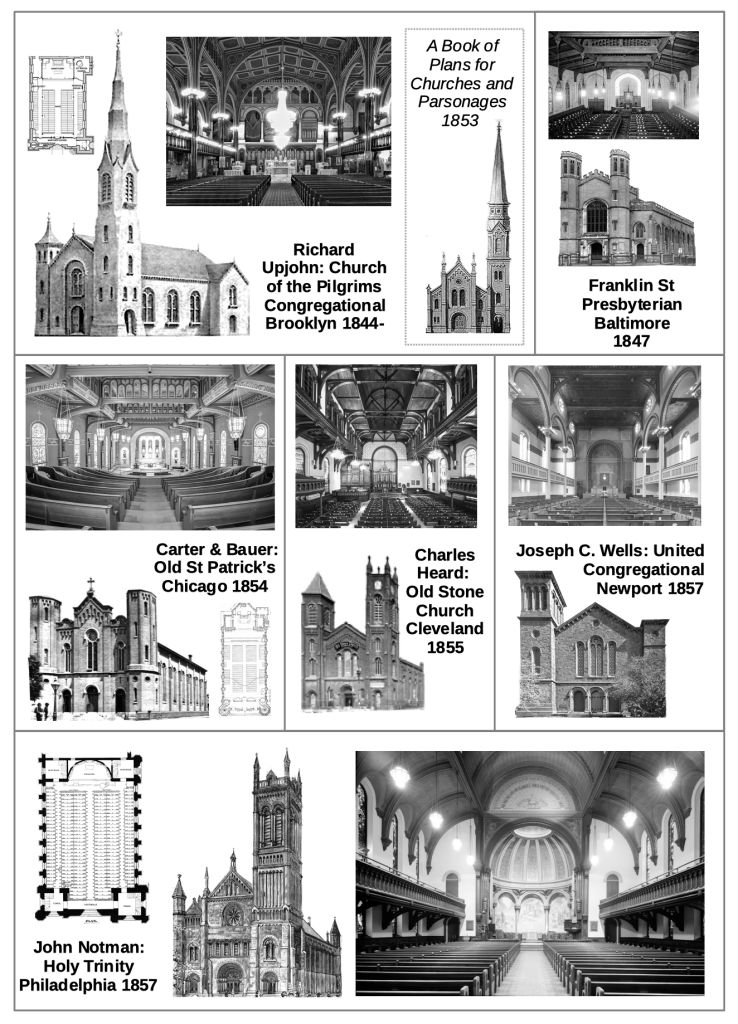

Midcentury Romanesque and Tudor Alternatives

By the middle of the 19th century, Gothic Revival styles dominated most new Episcopal and Catholic commissions. However some Protestant congregations still viewed the Gothic style with suspicion. They looked to Romanesque or Tudor alternatives. Richard Upjohn built the Congregational Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn (1844) in the Romanesque style. This church and other Romanesque designs were popularized in A Book of Plans for Churches and Parsonages published in 1853. The Presbyterians in Baltimore commissioned a church in the Tudor style in 1847, drawing architectural traditions from Protestant rather than Catholic England. In the 1850s, Romanesque plans proliferated among Protestant congregations. These churches typically contained wide halls with large galleries deriving from earlier American meeting house traditions. In many ways, the round-arched Romanesque style was perfect for the broad, open spaces demanded by Protestants. Even Episcopal and Catholic congregations sometimes abandoned their narrow, vertical Gothic spaces for open, horizontally oriented, round-arched ones, as seen at Old St. Patricks Chicago (1854) and Holy Trinity Philadelphia (1857).

Carpenter Gothic

By the mid-19th century, Gothic architecture was seen as acceptable, not just for ornate urban churches, but also for smaller scale rural churches built of wood. The earliest surviving “Carpenter Gothic” church is First Parish in Cambridge. It was a straight-forward Gothic structure built in the style of Ithiel Town that didn’t account for any particular special quality of the wood. However, at Winter Street Church in Bath Maine (1843) the unique potential of wood as a gothic form began to manifest itself. Winter Street’s facade contains beautifully carved gothic and classical motifs that seamlessly integrate into the structure as a whole.

The first masterpiece of Carpenter Gothic was Upjohn’s First Parish in Brunswick, Maine (1945-). A comparison of the exterior elevation Upjohn’s wooden Brunswick vs his stone St. Mary’s Burlington (1847) shows that Carpenter Gothic calls for a greater degree of vertical proportion. Upjohn understood that wood was an ideal material for a style of architecture that is essentially vertical, and that the verticality of wood demands proportionally greater attenuation. The interior ceiling at First Parish is also noteworthy. Upjohn extended the arrangement of hammer beamed trusses to the aisles and transept of the church, resulting in an inordinately elaborate, but nonetheless effective design.

A comparison between St. John’s Chrysostom (1851-) and Old Scotch Church (1876-) highlights the stylistic variety that Carpenter Gothic can effectively accommodate. St. John’s is decorative and playful while Old Scotch is compact, austere, and elevated. Yet both are masterpieces of woodwork. St. Luke’s Clermont (1857) showcases the gothic potential of jigsaw tracery which would go on to gain such popularity in domestic Victorian-era architecture.

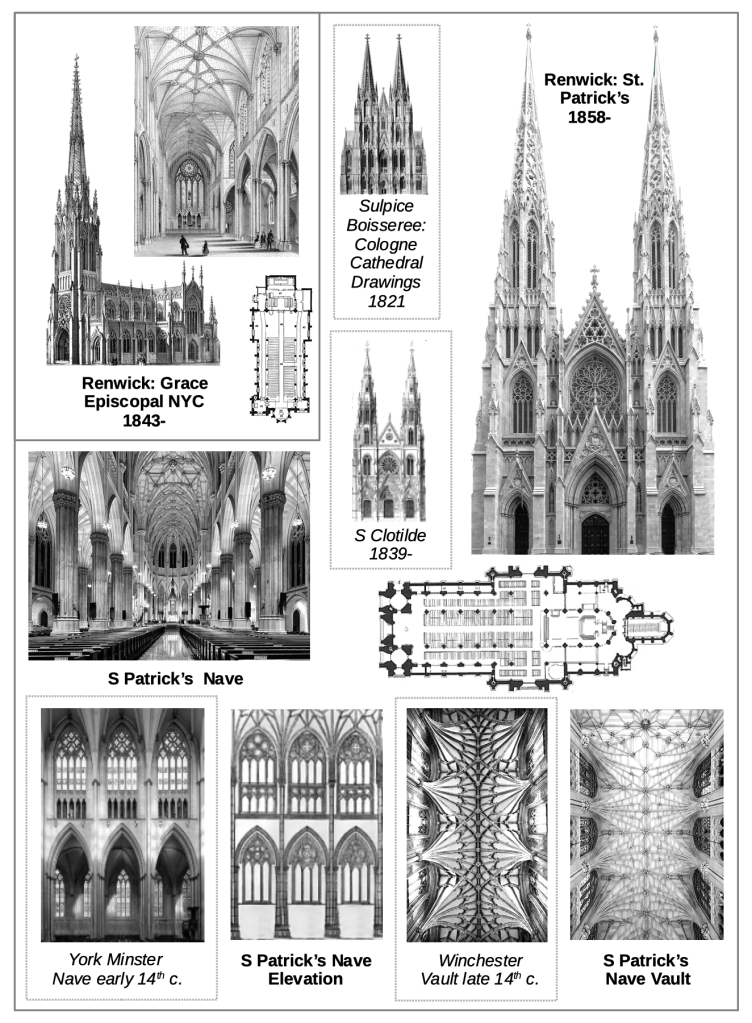

James Renwick Jr. and St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Two years after Upjohn’s Trinity was begun in 1941, American architect James Renwick Jr. created a similar design for Grace Episcopal in New York City. Unlike Trinity, Grace had prominent transepts and contained elements from the French Gothic tradition, such as gables over portals and curvilinear tracery. It also had a profusion of lace-like sculpture in the English Perpendicular Gothic style (15th c.), whereas Trinity adhered more closely to the earlier English Decorated Gothic style (14th c.). Renwick’s success at Grace won him the commission for St. Patricks’ Cathedral.

Renwick’s early designs for St. Patrick’s called for a single-towered church similar to Grace. But after a trip to Paris in 1855, he decided on a symmetrical two-towered plan similar to the new church of St. Clotilde in Paris (1839-). St. Clotilde was an academically-influenced attempt to recreate a High French Gothic Cathedral from the 13th century. However, unlike actual medieval Cathedrals, which had asymmetrical facades with towers of differing height, St. Clotilde was to have two identical towers. This decision was based on the fact that the original medieval designers intended their cathedrals to have symmetrically towered facades. Because construction of the medieval cathedrals spanned many centuries, plans were changed along the way, leading to asymmetry. A new symmetrical facade for Cologne Cathedral was also being built and detailed plans were published 1821, influencing the design of St. Clotilde and many other 19th century Gothic Revival structures.

Ruskin wanted St. Patrick’s to be built with an authentic stone vault, without resorting to modern materials like iron (as St. Clotilde had). However, the stone vault proved to be beyond the technical capabilities of American builders and the vault was eventually built in lathe and plaster. Without the stone vault, the planned flying buttresses were rendered irrelevant and had to be reduced so as not to collapse the nave in on itself.

The interior design of St. Patrick’s draws on a number of English models, including York Minster for the bay elevation and Winchester Cathedral for the vault. Nevertheless, Renwick’s final vault contains an original 8-point star design.

Another innovation was Renwick’s placement of the octagonal spire on the facade. Traditionally, octagonal spires were placed on square towers with four of their sides aligned with the fours sides of the square. However, Renwick placed the octagon so that four of its edges intersected with the center of each of the four sides of the square tower. This enhanced the vertical continuity between the tower and the spire.

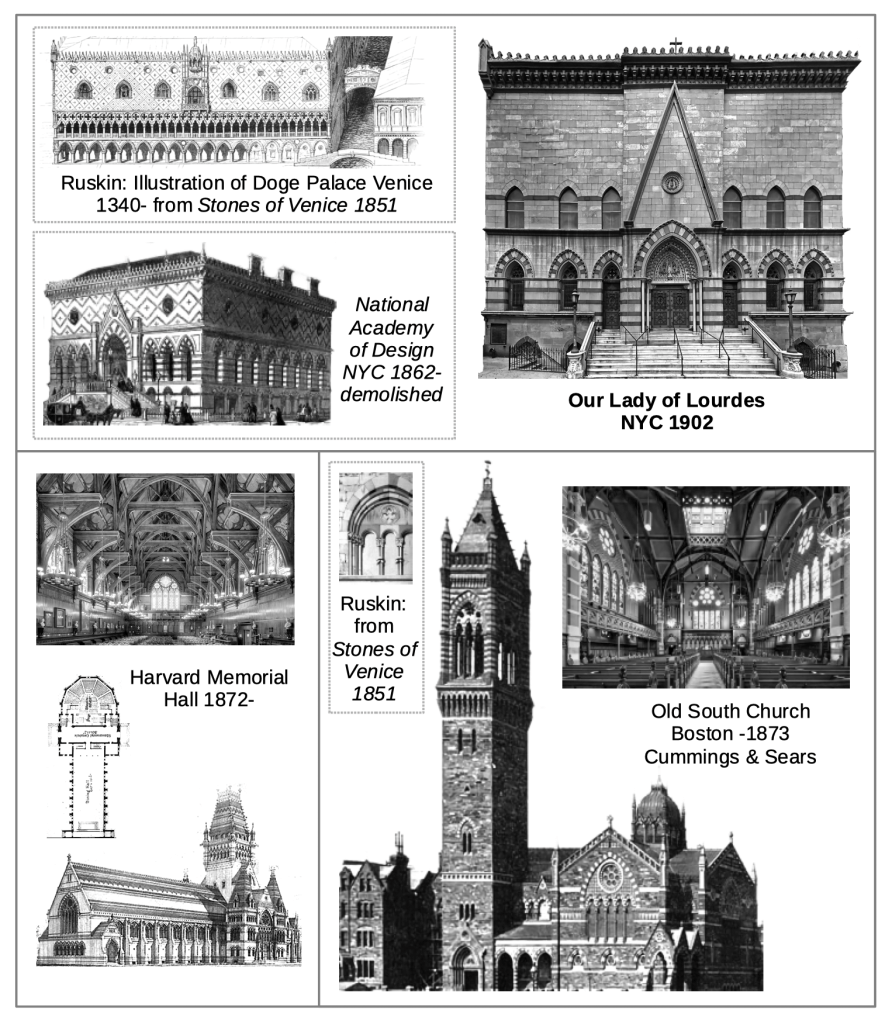

John Ruskin and High Victorian Gothic

As work on St. Patrick’s was progressing, the Gothic Revival took an Italian turn, influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and his championing of Venetian Gothic. The resulting style is often called “High Victorian Gothic” and is characterized by polychromatic masonry, Italian-style tracery and arcading, and a general sense of grandiosity. One of the most important works in this new style was the National Academy of Design in New York City (1862-) which was unfortunately demolished in 1901. However, many of its features were salvaged and placed on the facade of Our Lady of Lourdes NYC (1902).

Harvard Memorial Hall (1872-) and Old South Church in Boston (1873) were both built in the High Victorian Gothic style. Harvard Memorial Hall is included in this survey because it was built on a Gothic church plan, with a hammer beamed dining hall replacing the nave, a memorial to dead soldiers placed in the transept, and an amphitheater in the chancel based on Christopher Wren’s Sheldonian Theater in Oxford. Old South Church includes a wealth of High Victorian Gothic motifs, including the polychromatic tower based on St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice.

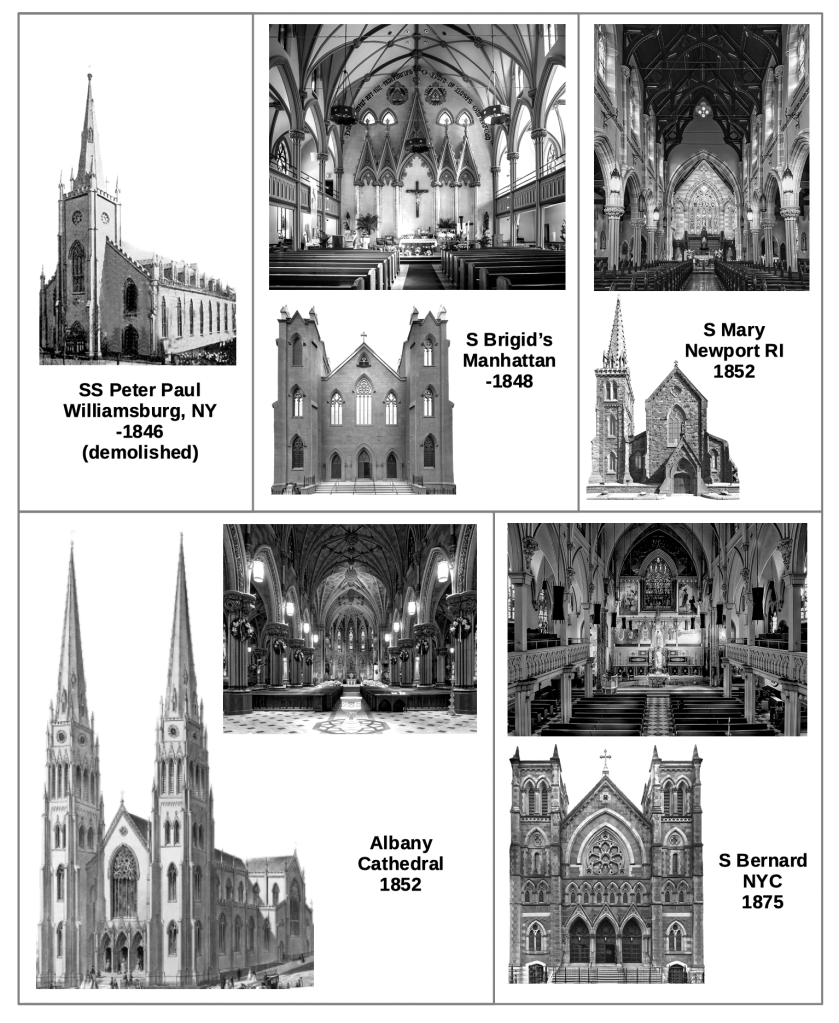

Patrick Keely and Catholic Gothic

Irish Architect Patrick Keely held a virtual monopoly on all the important Catholic commissions of the mid 19th century with the exception of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. His first church, S. S. Peter and Paul in Williamsburg (1846-) was built in the style of Ithiel Town’s Trinity on the Green (figure 5). The interior of his second church, S. Brigid’s Manhattan (1848) shows the influence of Batty Langley’s Gothick. By the time Keely built S. Mary’s Newport (1852), he had adopted the principles of the Episcopal ecclesiologists, including a nave with side aisles, a separate chancel, and steeply pitched wooden roofs. Albany Cathedral (1852) is Keely’s first masterpiece, with its enormous clustered piers topped by richly carved capitals in the English Decorated style championed by Pugin. Unlike Upjohn and Renwick, Keely had no issues with vaults built of lathe and plaster. By the time he built S. Bernard in New York City in 1875, Keely had abandoned the principles of the Ecclesiologists altogether, reverting to galleries, rejecting the chancel, and adopting flamboyant High Victorian polychromatic detailing. In each of these churches, Keely’s designs mirrored the broader trends of the Gothic Revival in America.

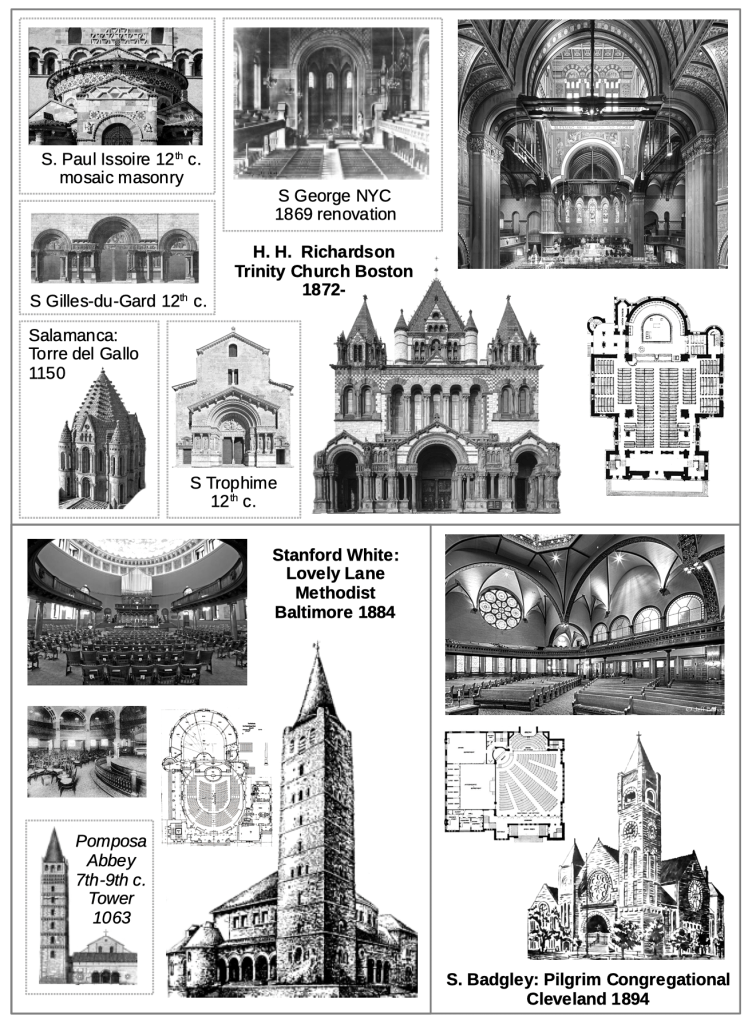

Richardsonian Romanesque

Architect Henry Hobson Richardson’s Trinity Church Boston (1872-) was so influential that it spawned its own style: “Richardsonian Romanesque.” Originally, Richardson had submitted a Gothic proposal for Trinity. However, with the growing popularity of Romanesque, Richardson switched styles and redesigned the crossing tower after the Romanesque Torre del Gallo at Salamanca Cathedral (1150). The chancel apse was an augmented version of S. George’s NYC (1869), a favorite preaching venue of Trinity’s charasmatic rector Phillip Brooks. The trefoil vault takes cues from Notman’s Holy Trinity Philadelphia (figure 10). Exterior detailing was inspired by the mosaic masonry of S. Paul Issoire and other Romanesque churches of the Auvergne in France. The portal is modeled on the French Provencal Romanesque of S. Gilles-du-Gard and S. Trophime, with their large sculptural programs.

Trinity was designed on a broad open plan preferred by Protestant congregations, even though it was built for a high-church Episcopal congregation (figure 10). While this choice was influenced by the celebrity of Phillip Brooks, it was also part of a broader trend in Protestant church architecture in the late 19th century which emphasized the theatrical dimensions of the church experience. The Richardsonian Romanesque churches Lovely Lane Methodist Baltimore and Pilgrim Congregational Cleveland were also built as vast, open amphitheaters with wrap-around galleries. Additionally, both these church plans included rows of Sunday School classrooms designed according to the “Akron Plan,” which was an attempt to reform religious education in late 19th century Protestant America. At Lovely Lane, these classrooms are aligned in a semi-circle resembling the chapels that radiated from the ambulatories of medieval churches. Lovely Lane’s tower takes its inspiration from the 11th century tower at Pomposa Abbey.

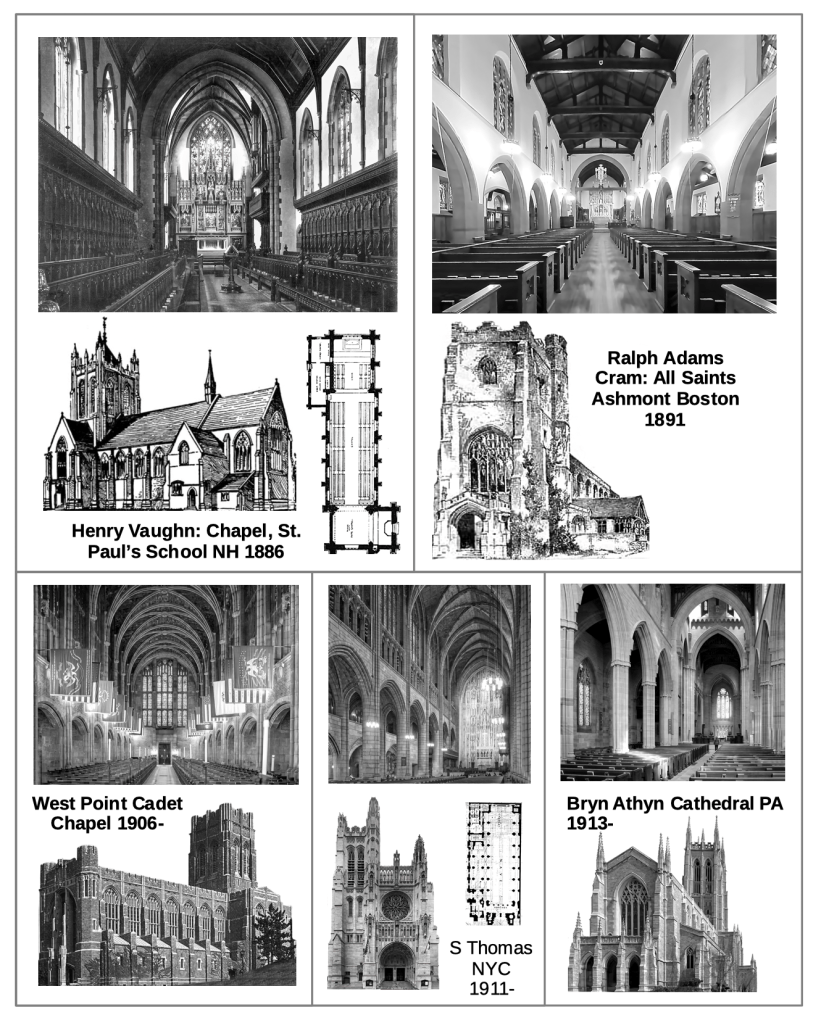

Ralph Adams Cram and the Perpendicular Gothic Revival

By the late 19th century, the Gothic Revival had gone into decline and was just one of many eclectic styles architects could choose from. Architect Ralph Adams Cram reawakened the Gothic Revival by revisiting the Perpendicular English Gothic style of the 15th century, which had been heretofore neglected in favor of the Decorated English style (14th c.) preferred by Pugin and the Ecclesiologists.

The Perpendicular Revival started in 1886, with Henry Vaughan’s Chapel at St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire. Ralph Adams Cram was so taken by the beauty of this chapel that he declared it to be the start of the “true” Gothic Revival. Cram’s first church commission was All Saints, Ashmont (1891) which showcased Cram’s emphasis on unity, bold massing, and elimination of extraneous details.

Cram’s beautiful West Point Cadet Chapel (1906-) solidified his reputation and he was soon given two important New York City Commissions: St. Thomas, and the completion of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, both of which featured vaults made entirely of stone. The medieval authenticity and constructional expertise of Cram’s firm was at its highest during the construction of Bryn Athyn Cathedral, where Cram formed a medieval style guild, bringing together craftsmen and grouping them into workshops and studios near the worksite. It was a laborious and expensive process, but resulted in a church that was perhaps more refined than any other built during the Gothic Revival.

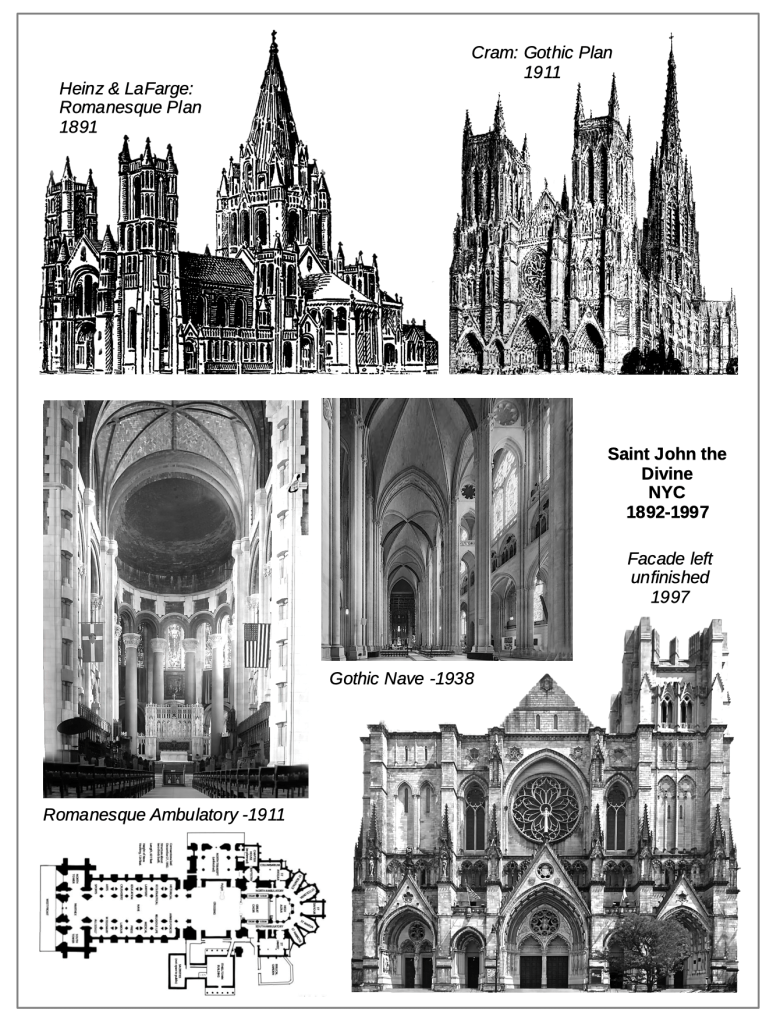

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine

The original 1891 plans for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine were made in the Romanesque style popular at the time. Its tower design resembled the Salamanca model used at Trinity Boston by H. H. Richardson (figure 15), likely due to the fact that John La Farge was one of the principal architects commissioned for St. John, and had worked closely with Richardson at Trinity. Construction progressed slowly, and by the time Ralph Adams Cram was called upon to take over the project in 1911, only the foundations of the nave and the eastern choir had been built. Cram redesigned the project in a French Gothic style and radically revised the nave. In most double aisled naves, the clerestory is placed over the main arcade facing the nave. But in Cram’s nave, the clerestory is placed over the second arcade, creating a highly original composition.

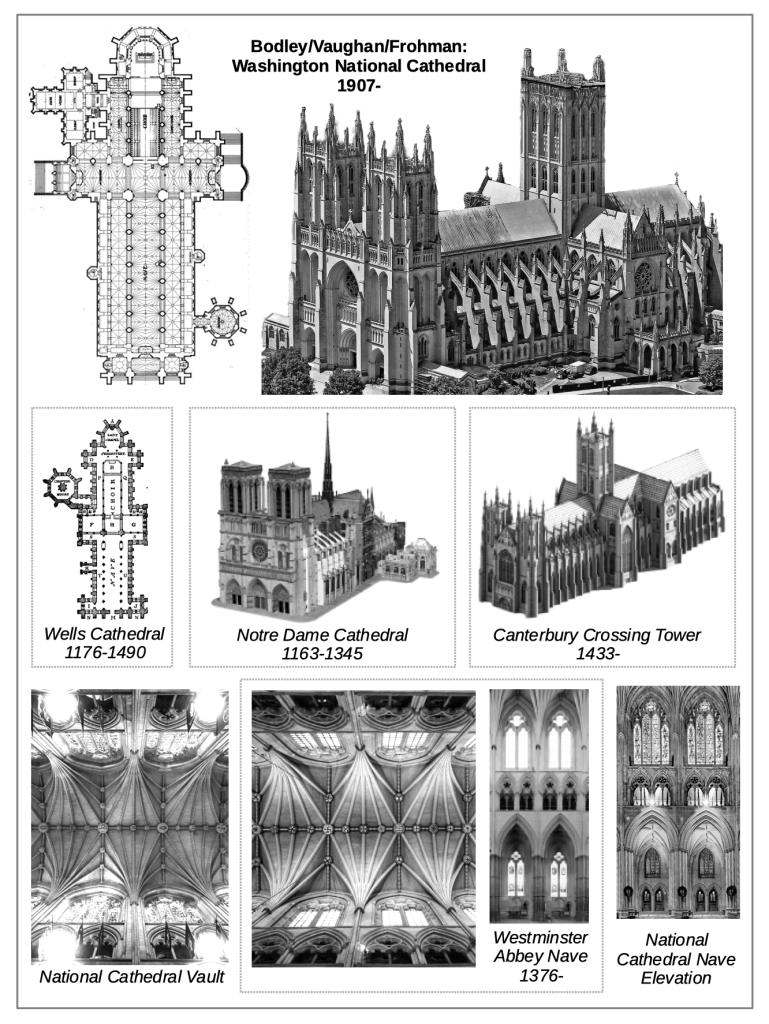

The National Cathedral

The National Cathedral in Washington D.C. is America’s third great Gothic Cathedral, along with St. John the Divine and St. Patrick’s. Designed by George Frederick Bodley, Henry Vaughan, and Philip Hubert Frohman, it takes inspiration from both French and English models. Its overall proportions are English, with a long transept and a relatively low nave elevation. Its crossing tower seems to have been inspired by the 15th century crossing tower at Canterbury. But the proportions of its facade are based on the Cathedral of Notre Dame, albeit with deeply recessed arcades characteristic of Decorated English Gothic (see the facade at Peterborough Cathedral for example). The dramatic flying buttresses were also designed in the French style. Its nave bay elevation and vault seem to have been derived from Westminster abbey, albeit with wider bays and four-light clerestory windows replacing Westminster’s two-light windows. The National Cathedral vault is very similar to Westminster’s but with an additional rib added to the clerestory portion of the vault.

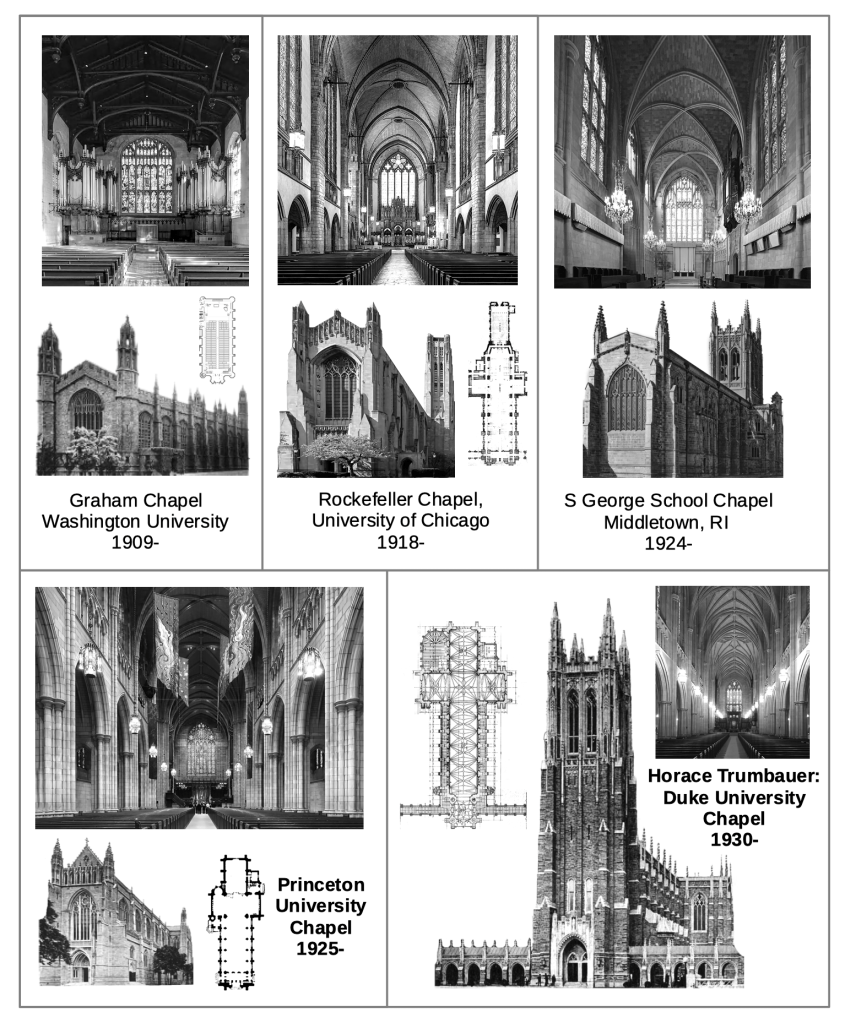

Collegiate Gothic Chapels

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many college campuses were built in a Perpendicular Collegiate Gothic style championed by Ralph Adams Cram, who was the principal architect of Princeton University. Most of the collegiate chapels shown above derive from the King’s College model first used by Ithiel Town at the Old New York University in 1835 (figure 4). Bertram Goodhue’s Rockefeller Chapel presents a dramatic version of this model, with deeply recessed windows, boldly massed buttresses, and a set of tall, narrow statue niches on its gable. St. George’s Chapel by Cram is perhaps the most refined of these school chapels, while Duke University’s Chapel is the grandest, with a tower as wide as both the nave and aisles, modeled on the crossing tower at Canterbury Cathedral (figure 18).

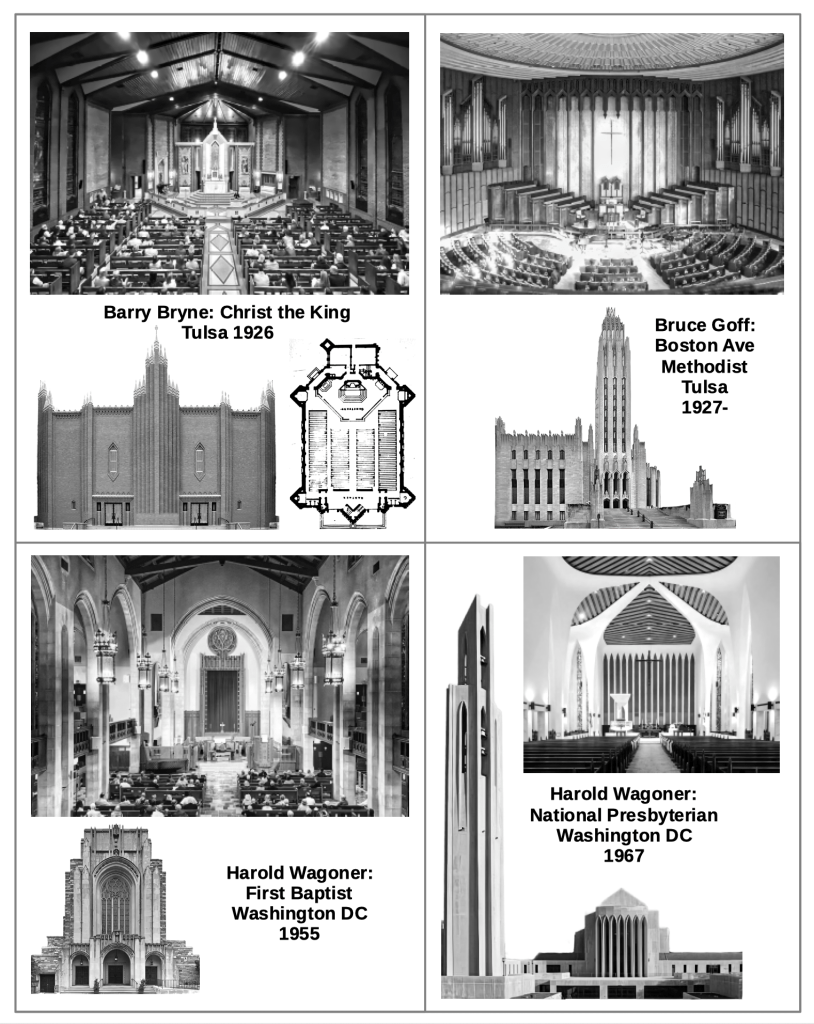

Art Deco and Modern Gothic

As the 20th century progressed, the Gothic ethos of verticality and monumentality became abstracted into Art Deco. Tulsa, Oklahoma is home to Art Deco’s two finest churches, Christ the King (1926) by Barry Byrne, and Boston Avenue Methodist (1927-) by Bruce Goff. Christ the King has a symmetrical facade and a traditional rectangular interior decorated in diamond shaped geometries. Boston Avenue Methodist is a sprawling, asymmetrical complex, like something out of Batman’s Gotham City, with a large amphitheater-like sanctuary glittering with ornamentation.

The Art Deco style was short lived but resurfaced in the mid-century “Modern Gothic” style of Harold Wagoner, whose National Presbyterian Church (1967) is a blend of Art Deco and mid-century minimalism. Wagoner’s First Baptist (1955) revisited the Collegiate Gothic of Bertram Goodhue’s Rockefeller Chapel (figure 19), albeit with a more minimalist interior. Wagoner’s mix of modernism, traditional Gothic, and Art Deco reflected the adventurous and experimental nature of mid -20th century church design.

New Classicist Gothic

Church architecture went into decline in the 1970s due to declining memberships and changing financial priorities. The post-modern styles of the late 20th century riffed on classical motifs, but rarely on Gothic ones. In the 21st century, a New Classicist movement has emerged, focusing on building in traditional styles. Most of these styles are classical, but there have been a few Gothic commissions as well.

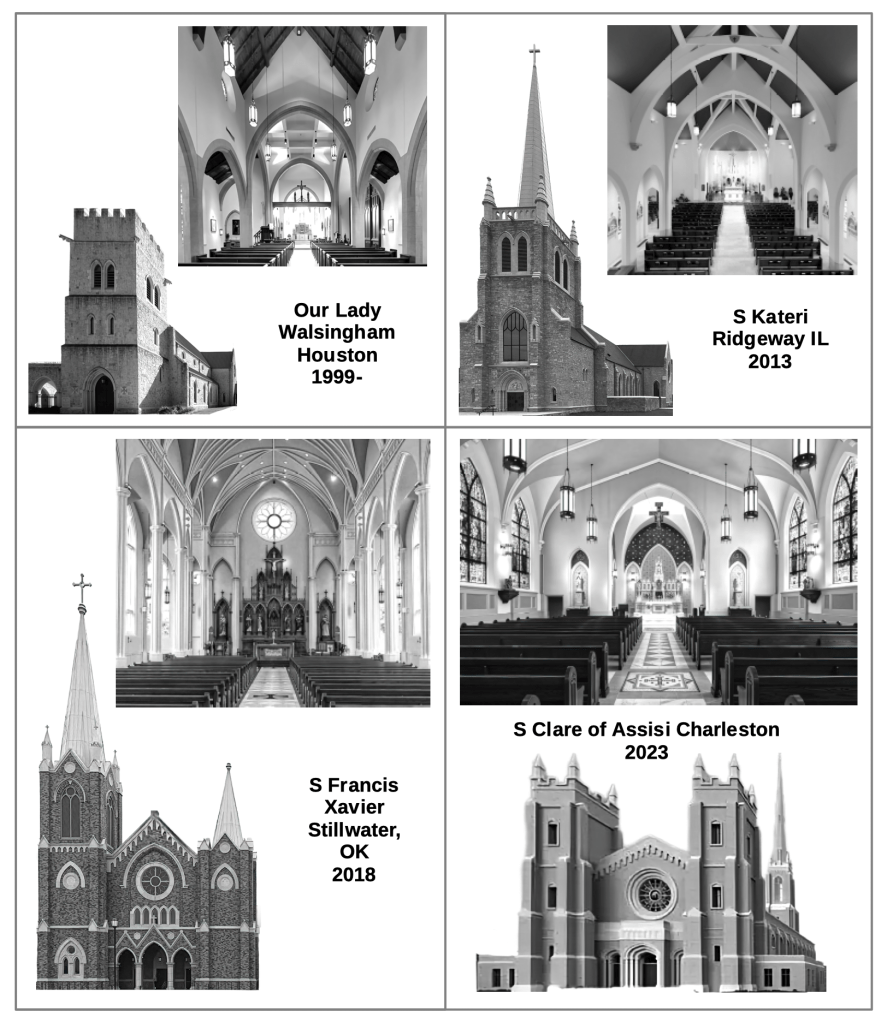

Architect Ethan Anthony built two gothic parish-style churches. Our Lady Walsingham Houston (1999-) was designed in an Early English style inspired by the churches in the Walsingham area in Norfolk. Its interior is a sparse mixture of stone, plaster, and wood vaulting resembling medieval prototypes. St. Kateri (2013) is a simplified version of a Cram-style perpendicular Gothic parish. Its interior is smooth and minimalist, but retains an overall gothic flavor.

The architectural firm Frank & Lohsen’s St. Francis Xavier (2018) adopted a polychromatic “ginger-bread” style while its interior seems to draw inspiration from the pre-Pugin work of Patrick Keely (see figure 14, St. Brigid). Frank and & Lohsen’s St. Clare of Assisi (2023) contains a dramatic facade with two towers jutting forward and a receding central section, an arrangement used by Patrick Keely at St. Brigid and Albany Cathedral (figure 14). The interior may have been influenced by the early Gothic Revival work of Ithiel town. It contains a shallow pointed groin vault similar to St. Luke’s Rochester 1824 (figure 5).

Leave a comment