Early Renaissance: Brunelleschi and Alberti

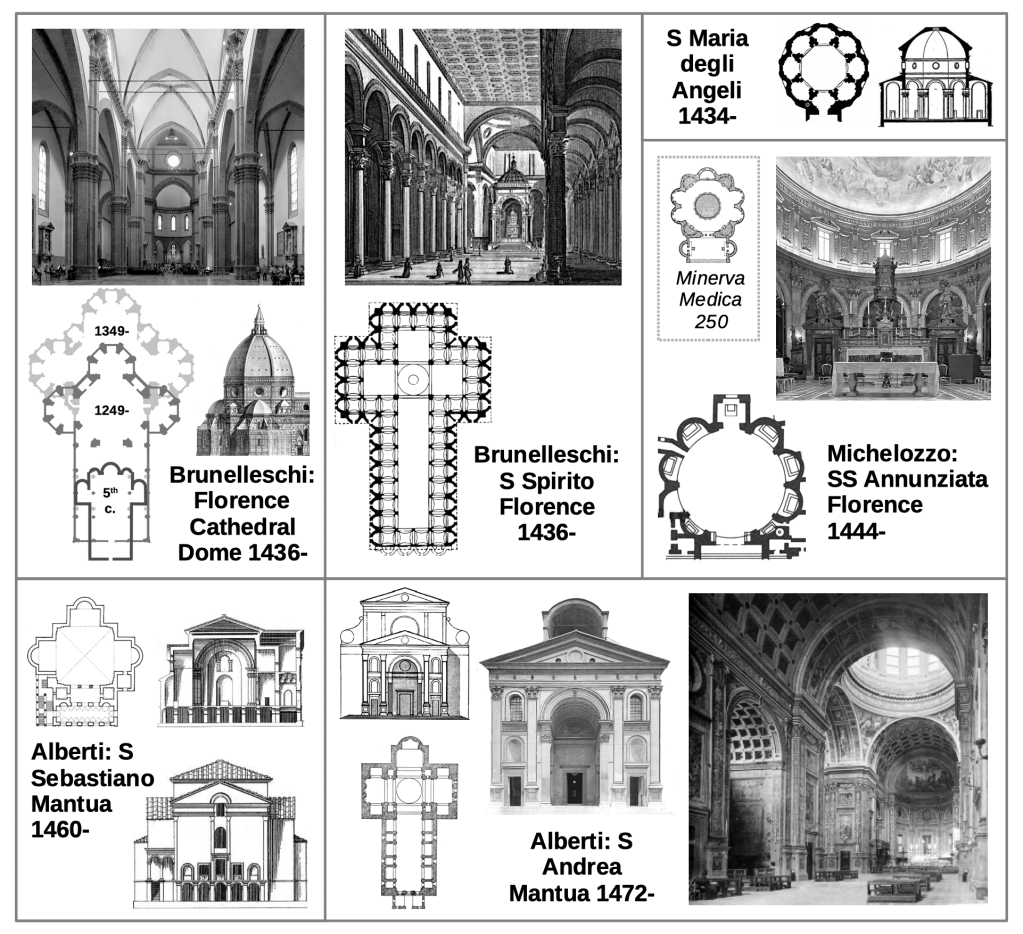

During the Florentine Renaissance, rectangular basilican plans were combined with Greek Cross-style central plans. This consolidation had began as early as 1249, when a quatrefoil floor plan was made for a new Florence Cathedral with choir and transept wings of equal size and shape. This plan was expanded in 1349 and it took nearly a century to figure out how to build a dome large enough to cover the vast area. The feat was eventually engineered by the architect Brunelleschi who proposed a double dome: an octagonal pointed outer dome supported by a shorter interior dome (1436-).

Like Florence Cathedral, Brunelleschi’s church of S. Spirito (1436-) was also built on a centralized Greek Cross plan with an extended nave. It featured an aisle that wrapped around the entire perimeter of the church, further highlighting the church’s centralized uniformity. Alberti’s S. Andrea Mantua (1472-) is likewise built on a Greek Cross plan with extended nave, designed around a series of interlocking triumphal arches. Alberti’s facade tied in the triumphal arch theme from the interior, combining it with a temple portico motif. This facade couldn’t cover the high barrel vaulted nave, leaving an exterior void that was left incomplete. Alberti may have intended a larger facade, as suggested in the drawing above.

Purely centralized plans from the early Renaissance include Brunelleschi’s S. Maria degli Angelo (1434-), Alberti’s S. Sebastiano (1460-), and Michelozzo’s chapel at SS Annunziata (1444-), which takes its floor plan from the Roman temple Minerva Medica (250), highlighting the increasing interest Renaissance architects were taking in antique Roman models.

The Lombardian Renaissance

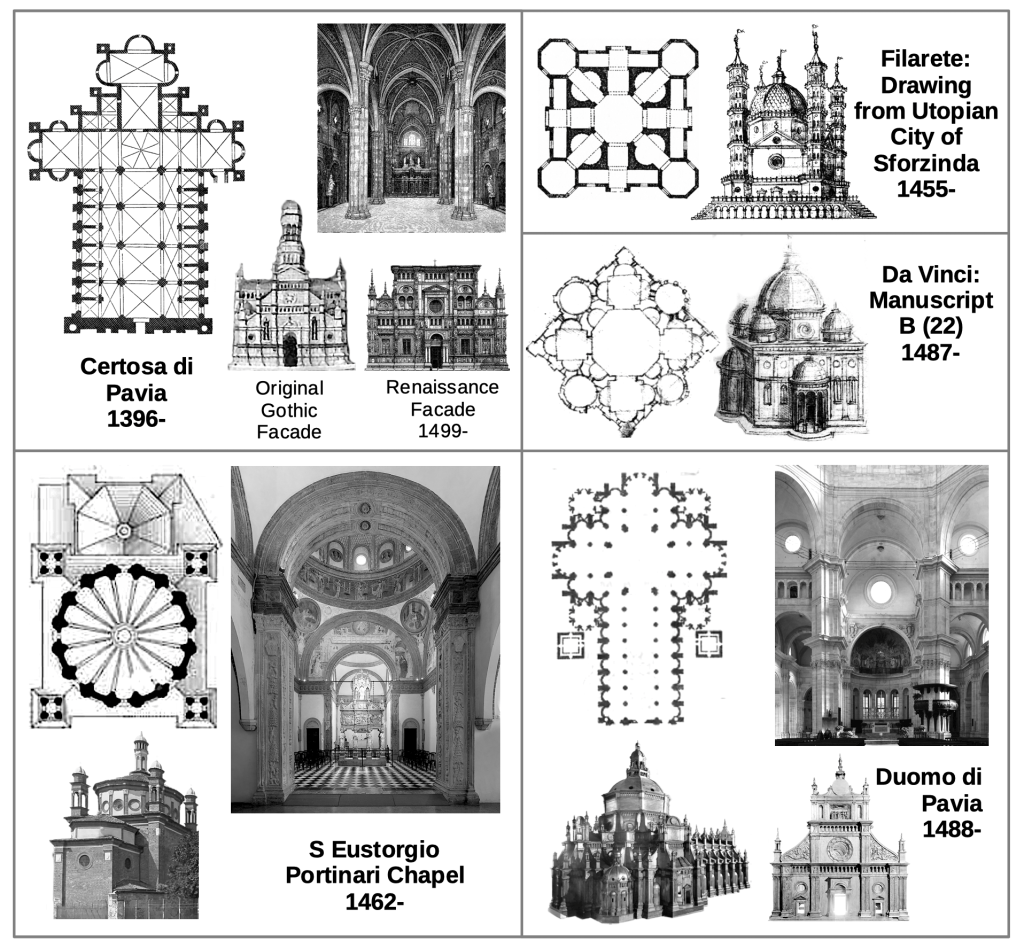

Centralized cross plans with long naves were also built in Lombardy. The interior of Certosa di Pavia (1396-) was built in the Gothic style with a renaissance facade added after 1499. The Duomo of Pavia (1488-), built a century after Certosa, has a wonderfully elaborate centralized plan resembling some of Leonardo Da Vinci’s inventive but unbuilt designs like the one from Manuscript B (22) drawn circa 1487.

Filarete, a Florentine architect working in Milan, created a unique central-plan chapel for his unbuilt utopian city of Sforzinda in 1455. The Portinari Chapel (1462-) attributed to Filarete, is a more modest version of the one designed for Sforzinda.

Donato Bramante

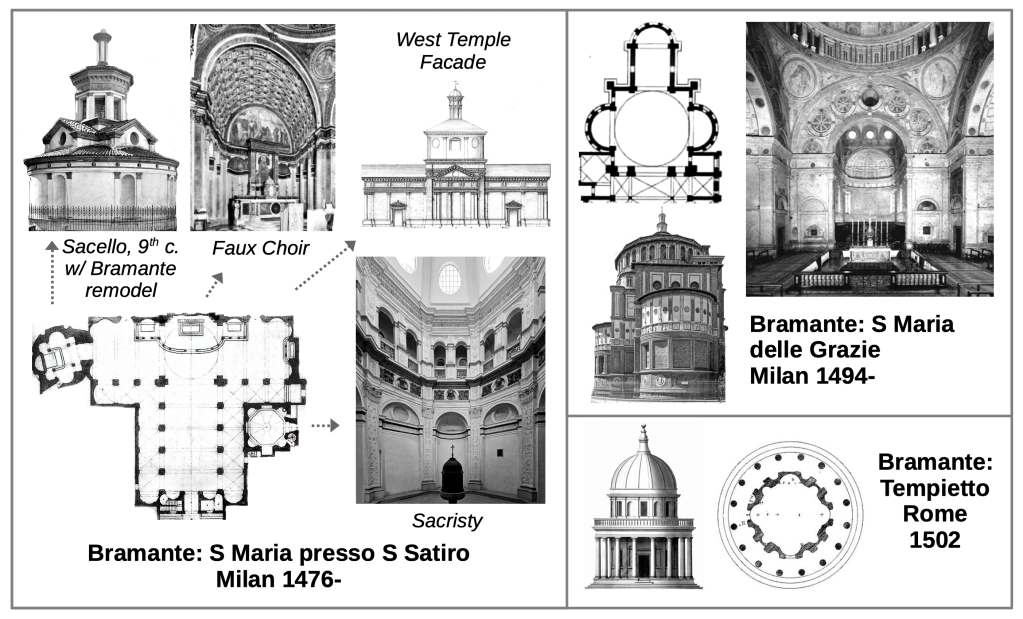

Donato Bramante’s first important church commission, S. Maria presso St. Satiro Milan (1476-), illustrates the importance given to centralized plans during early Renaissance. Bramante remodeled the existing church with a painted trompe-l’œil, choir which gives the illusion of a centralized plan scheme even though it is built on a T-transept plan. Bramante also remodeled the attached 9th Sacello in a style resembling Filarete’s Portarini chapel (figure 2) and added an octagonal sacristy.

Bramante’s centralized crossing dome at S. Maria delle Grazie Milan (1494-) illustrates the ornate Lombardian style with its polychromatic brick masonry, rows of arcades and circular windows. Bramante moved to Rome, abandoning the Lombard style for the pure classicism of the Tempietto (1502). This mausoleum, modeled on the ancient Temple of Vesta (1st c. BC), became an icon of Renaissance classicism and influenced generations of later architects.

The Evolution of St. Peter’s Basilica

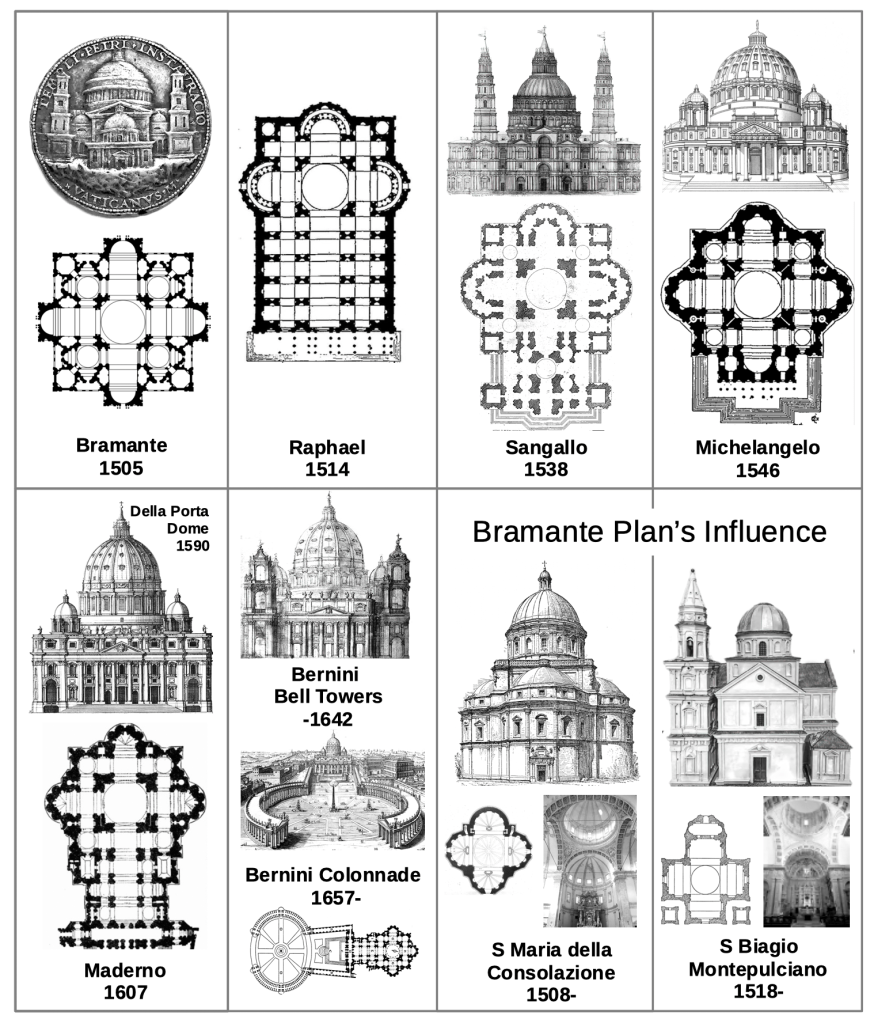

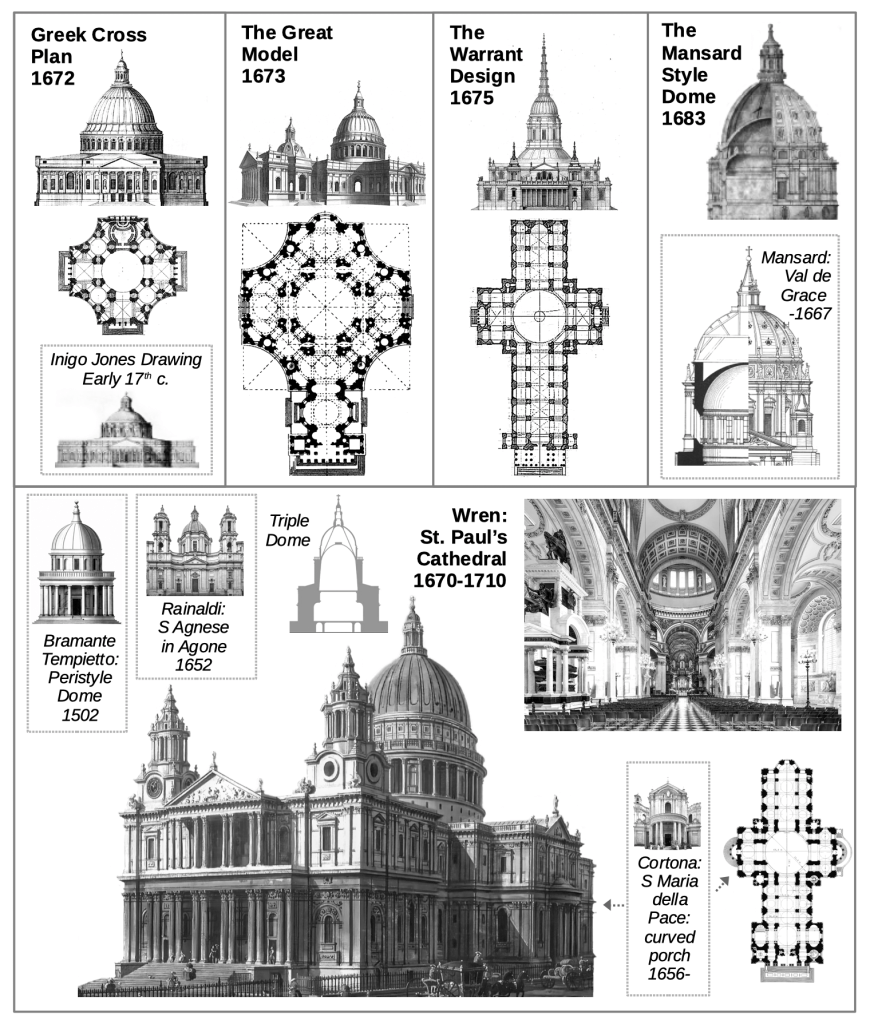

The history of the development of the design of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome highlights the ongoing debate between the advocates of centralized versus rectangular plans. Renaissance architects preferred centralized plans for philosophical reasons. An observer standing in the middle of a centralized church embodied of the humanist ideal of “man as the measure of all things.” This notion clashed with the traditional idea that churches were supposed to be designed for liturgical processionals in rectangular basilicas oriented towards an altar in the east. The Catholic authorities were initially open to Bramante’s centralized proposal of 1505, which was memorialized on a coin, highlighting the debt it owes to Filaret’s Szorzinda chapel (figure 2) with its four turret-like towers. But with Bramante’s death in 1514, the project was turned over to Raphael, who restored a longitudinal plan that nevertheless kept Bramante’s basic plan for the crossing with slight modifications in proportion, adding three ambulatories around the apses. Raphael died in 1520 and the plan was passed to Sangalo, who compromised between Raphael and Bramante, returning to the central plan, but adding a large atrium instead of a nave. When Sangalo died, Michelangelo returned to a centralized plan based on Bramante’s original, eliminating Sangalo’s atrium and Raphael’s ambulatories. With the ambulatories gone, Michaelangelo needed thicker, heavier outer walls to support the lateral forces pushing outward from the tower. He added a surrounding attic story to the entirety of the exterior walls. He also reduced the height of the eccentric Filarete-style towers and added a simple temple portico to the facade.

By the time Maderno took on the project in 1603, most of the work on the central crossing had been completed. To this, Maderno added a nave and a wide, prominent facade. These additions had the unfortunate effect of obstructing the view of the dome. So in 1657, Bernini added a long, sweeping colonnade in front of St. Peter’s to give worshipers a chance to appreciate the silhouette of the dome from a distance. Its unique design, widening as it approached the facade, created the impression that the colonnade was longer than it actually was. These sorts of optical illusions were common features of Baroque architecture. Bernini also added corner towers to the facade, but these were soon removed due to structural failings in the foundation.

Bramante’s original dome was designed as a single, cement shell. However, his four crossing piers were insufficient to sustain such a dome. These crossing piers were the only part of the church that survived from Bramante’s time. Sangallo raised the profile of the dome by adding the double-shelled innovation from Florence Cathedral (figure 10). He also reinforced Bramante’s piers. Michelangelo kept to Sangallo’s double-shelled plan, but seems to have lowered the profile, making it more hemispheric, although there is some debate about this, due to conflicting evidence in the original drawings. Architect Giacamo della Porta built the final dome with its ovoid profile, slightly higher than Michelangelo seemed to have intended. It is the highest dome in the world when measured from the floor to the lantern ceiling.

As the design of St. Peter’s evolved, the various stages of the design process sometimes had an influence on surrounding churches, notably S. Maria della Consolation (1508-) and S. Biagio Montepulcelo (1518-), both of which borrowed aspects of Bramante’s centralized St. Peter plan.

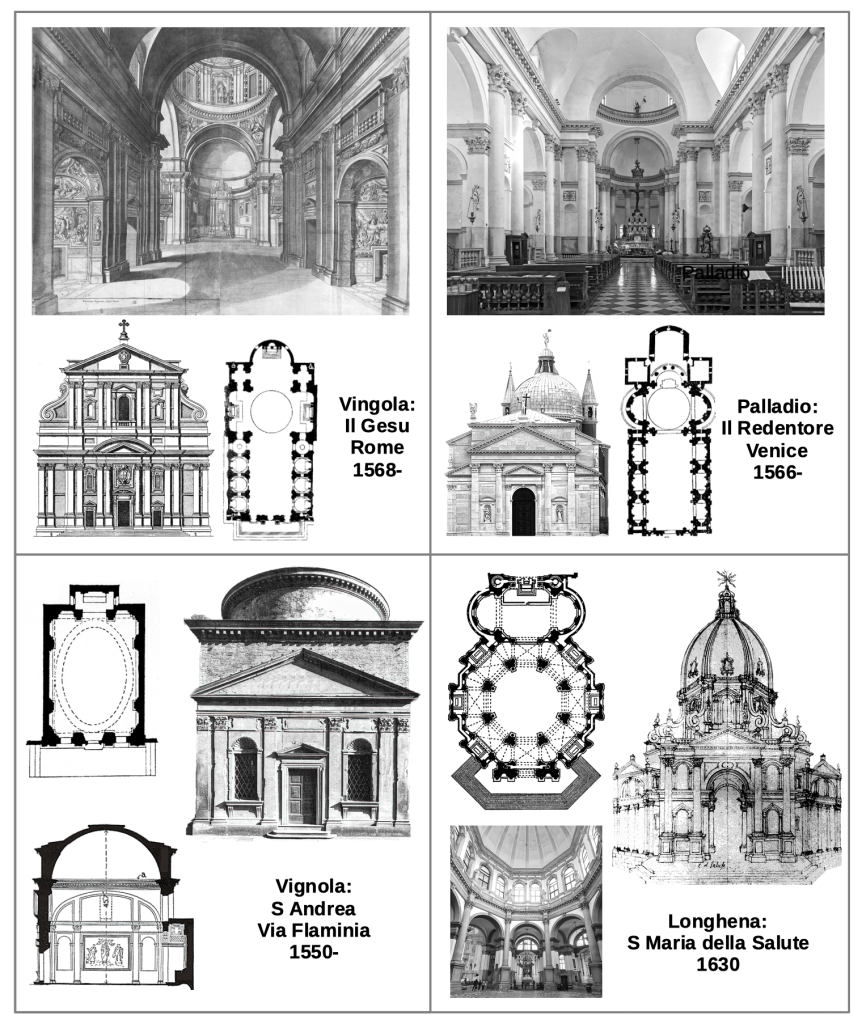

Counter-Reformation Plans

In the mid 16th century, Jesuit reformers advocated a return to the basilica plan, albeit with wide open naves built for large congregations to listen to their sermons. This was inspired by counter-reformational competition with Protestants, who downplayed liturgical aspects of worship to focus on preaching. Vignola’s Il Gesu (1568-) was the headquarters of the Jesuit movement and its architecture exerted a strong influence on Catholic architecture going forward. The floor plan of Il Gesu derives from Alberti’s triumphal arch-style construction at S. Andrea Mantua (figure 1). Both these churches convert the traditional aisles into chapels, a practice first introduced in Catalan gothic churches (See Church Floor Plans Part 1.) Vignola’s Il Gesu is filled with light, due to large open windows piercing the barrel vault. Palladio’s Il Redentore Venice (1566-) also emphasizes lighting and openness, aided by its tall chapel arcades. An emphasis on dramatic and theatrical lighting was to become a central motif of Baroque architecture.

Vignola’s S. Andrea Via Flaminia (1550-) features one of the first oval domes, a device which became popular in the Baroque period. Unlike later Baroque churches however, Vignola’s chapel is built in a severe and academic form of Renaissance classicism derived from the Roman Pantheon.

Longhena’s unique octagonal design for S. Maria della Salute Venice (1630-) came about as the result of a competition. Other architects had submitted standard basilica plans, but Longhena’s extravagant design wowed the judges, a sign of the increasing individualism and creativity of 17th century Baroque architecture.

Italian Baroque Churches

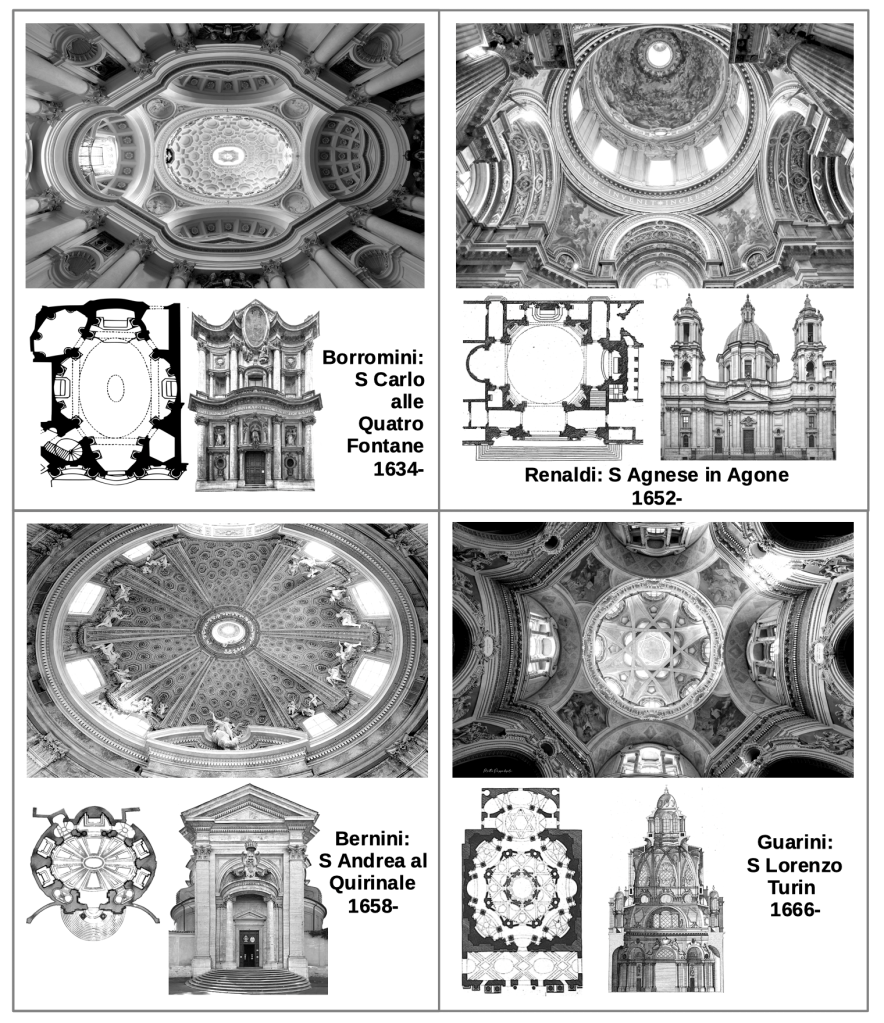

By the mid-17th century, centralized plans reappeared, often in oval shapes, as first introduced by Vignola at S. Andrea via Flaminia (fig. 5). In 1609 Johannas Kepler had established that planets move in ellipses, not circles. This was part of a new empirical approach to science that prioritized observation and experimentation over rational, platonic theories. Ovals were thus seen as a more accurate symbol of God’s creation than perfect circles. Ovals also gave interiors a theatrical dimension suggestive movement through space: open-ended, off-kilter, swirling, and infinite.

Borromini’s oval at S. Carlo alle Quatro Fontane (1634-) is oriented longitudinally along what would have been the nave of a traditional church, as Vingola’s had been. This central oval had attached apses also in ovoid forms, creating a highly dynamic space.

Bernin’s S. Andrea al Quirinale (1658-) oriented the oval sideways, parallel to the facade, a radical decision that departed from both the basilican longitudinal tradition and the centralized tradition. This unique arrangement had been anticipated by S. Agnese in Agone( 1652-) which consisted of a central octagon extended sideways with large “transept” apses, creating an ovoid effect, which, like S. Andrea al Quirinale, was oriented parallel to the facade.

Guarani’s S. Lorenzo, Turin (1666-) was built on a centralized plan devoid of ovals. However S. Lorenzo consisted of an intricate geometric system of convex and concave semi-circles, like those introduced in the facade of Borromini’s S. Carlo, which was built on a wave-like set of convex and concave forms. Precedents for Guarini’s dome can be seen at S. Sepulchre at Torres del Rio (1200), with its banded Islamic vault (figure 5, Church Floor Plans Part 2) Guarini’s complex geometric style, and Borromini’s inventive use of ovoid forms inspired Baroque architects in Germany and Austria, who took these forms to fantastic new lengths.

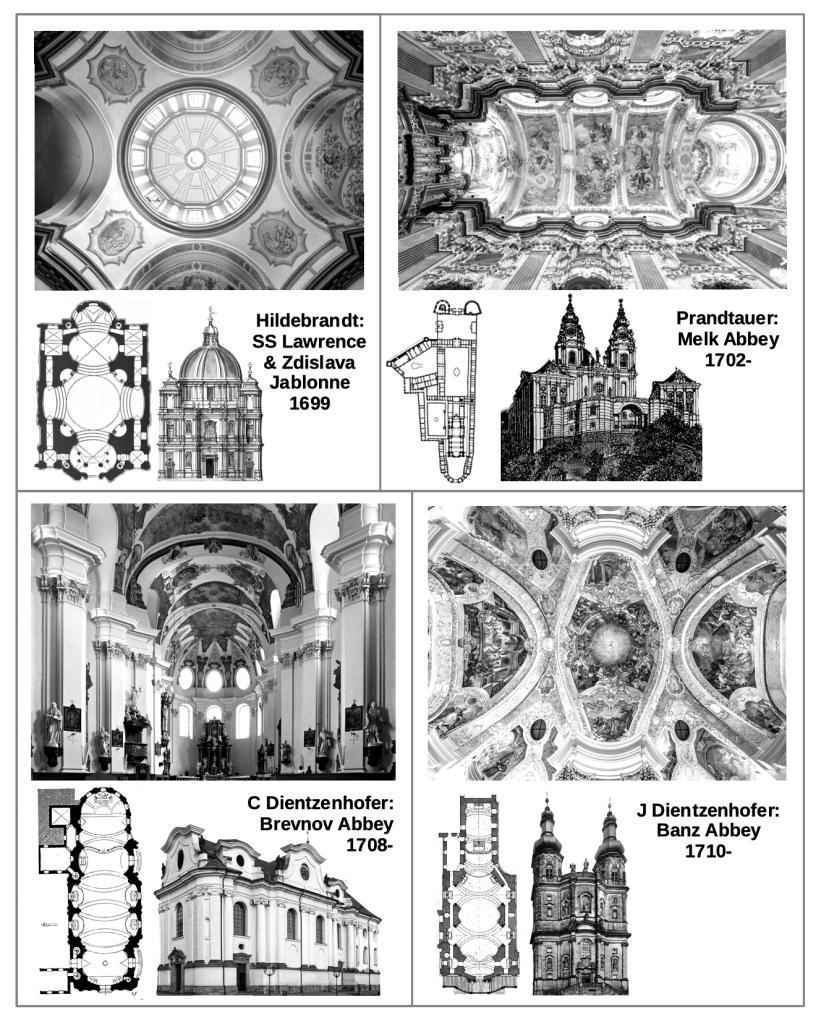

German Baroque

Germany had been devastated by the 30-Years War in the mid-17th century, but by the early 18th century, German Catholicism and monasticism was experiencing a revival. A militant and theatrical form of ecclesiastical architecture emerged, building on Italian baroque models. The Melk Abbey complex (1702-) dramatically situated on an outcropping above the Danube, is representative of the new style. Its chapel retains a traditional longitudinal floor plan, but animated with the dynamic forms of Italian baroque. Ovoid forms were introduced at SS Lawrence & Zdislava in Jablonne, Czech Republic (1699), which contains a central dome surrounded by four ovals.

Brothers Christoph and Johann Dientzenhofer built churches at Brevnov and Banz Abbey consisting of a series of intersecting ovals running the full length of the church, giving the processional journey along the nave a new, surging dynamic.

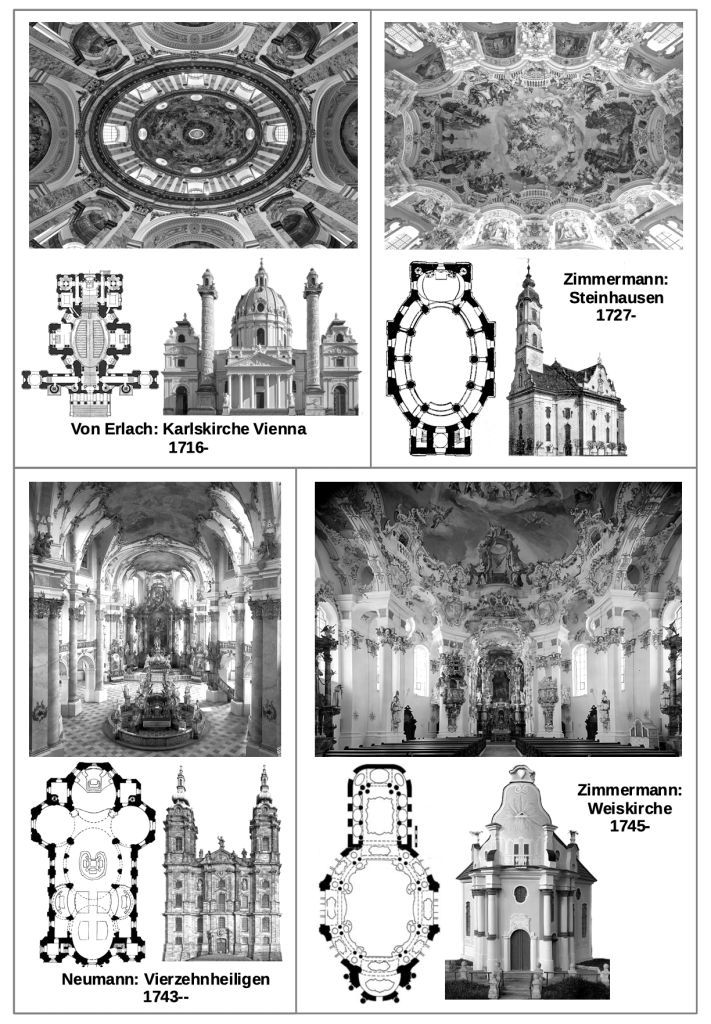

Von Erlach’s masterpiece, the Karlskirche in Vienna (1716-), presents a more restrained, classical structure influenced by Rinaldi’s S. Agnese in Agone (1652-). But German architects Zimmermann and Neumann built on the swirling forms of the Dientzenhofer brothers (figure 7) to create some of the most hallucinatory architectural structures ever made, including Vierzehnheiligen (1743-) and Weiskirche (1745-). These churches combine the complex Baroque geometries of Borromini and Guarini with Rococo filigree in the French style. French architects only used the ornate Rococo style as a gloss on top of more restrained classical structures. But the German architects combined rich Rococo ornamentation with complex Baroque structural designs, resulting in an architecture unsurpassed in its flamboyance.

Early Protestant Architecture

The Italian and German Baroque styles emerged from the Catholic counter-reformation, which was a backlash to the earlier Protestant reformation. The counter-reformation sought to keep parishioners away from Protestantism by providing an emotive, richly ornamented worship experience in Catholicism, contrasting sharply with the austerity of Protestant worship, which rejected all iconography.

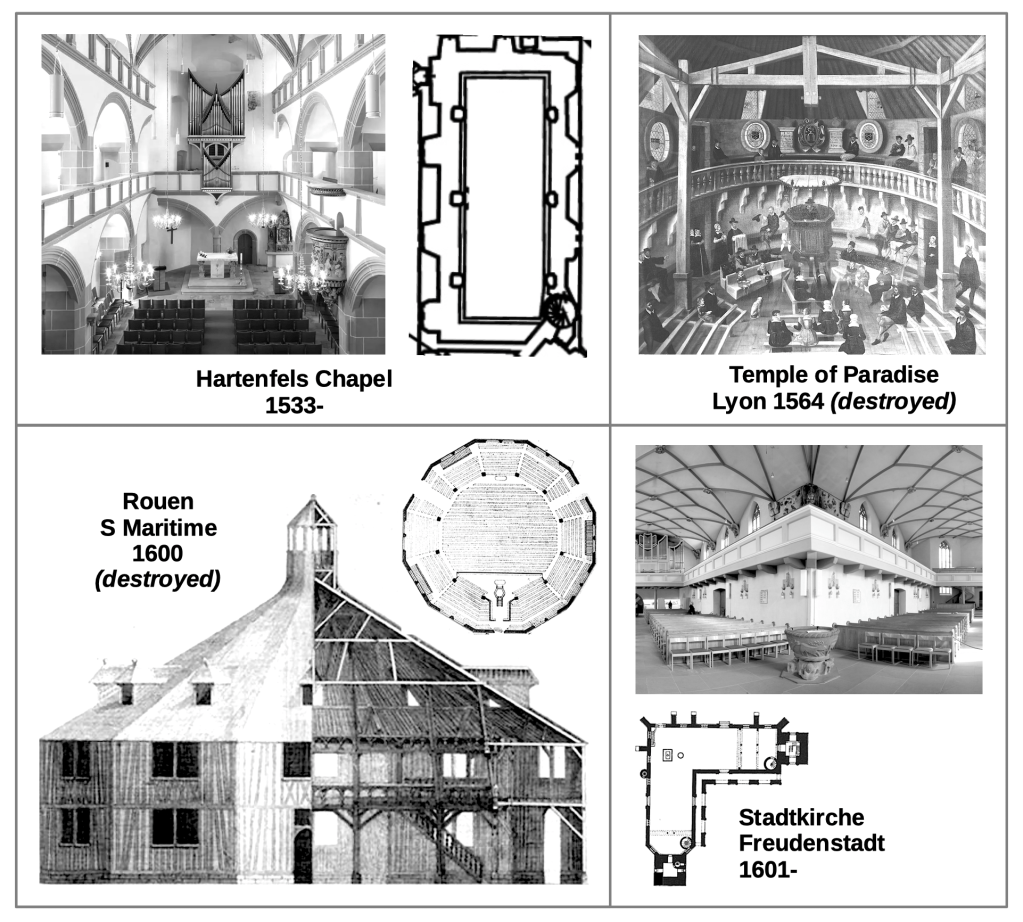

The earliest Protestant chapel ever built was at Hartenfels Castle (1533-). Martin Luther assisted in its design, which featured a single, open area, without chapels or apses and devoid of iconography. Its altar was set away from the wall so the priest could administer sacraments while facing the congregation. A pulpit was placed in the center of the right side wall, so that the preacher could be easily heard by all.

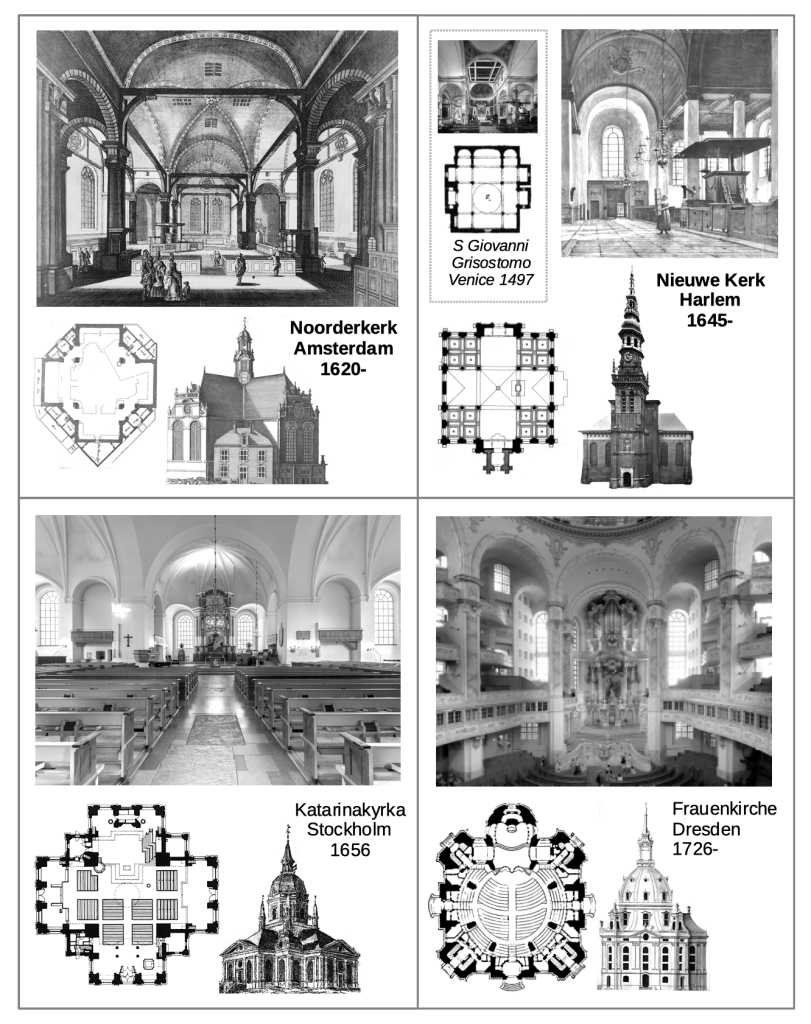

Early Protestant churches were built on a number of different floor plans, but they all shared an emphasis on the centrality of preaching and simplicity in ornamentation. A painting of the now lost Huguenot chapel at Lyon (1564) shows a circular building with a dominant central pulpit surrounded by benches and galleries. Drawings also survive of the similar, now lost church Rouen’s S. Maritime (1600). Early German Protestant churches were sometimes built in an L-shape, with the sexes divided into one of two naves, both facing a central pulpit, as at Stadtkirche Freudenstadt (1601-).

Northern Protestant Architecture

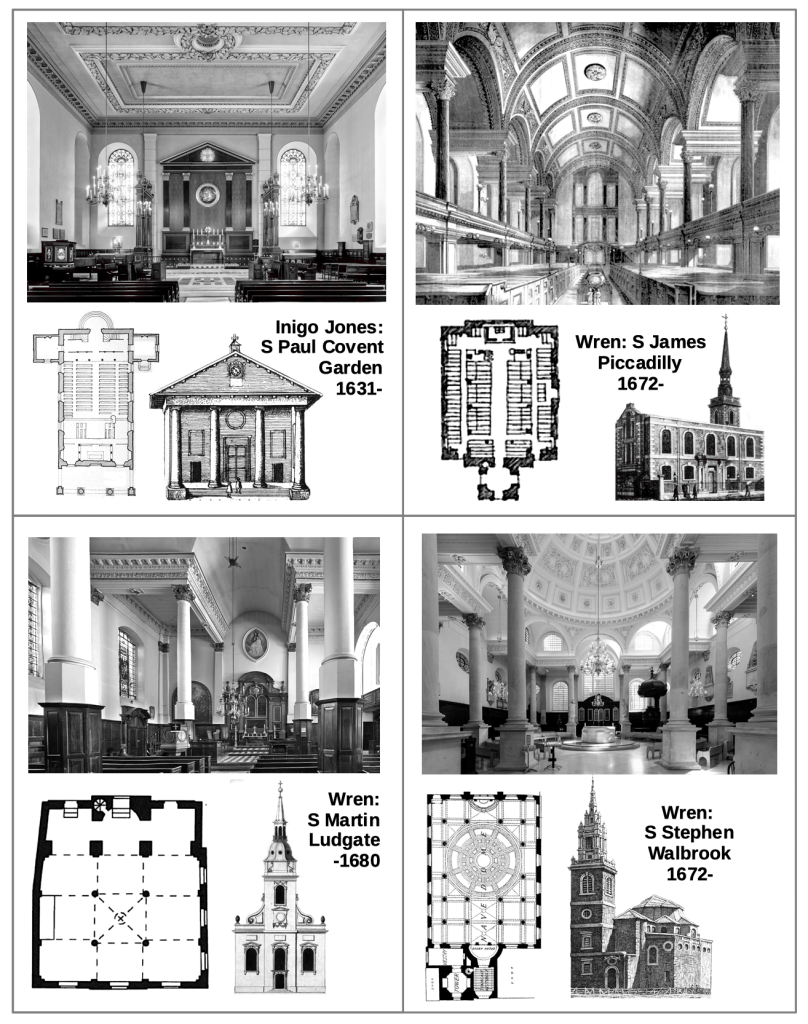

Christopher Wren

Evolution of the Design at St. Paul’s Cathedral

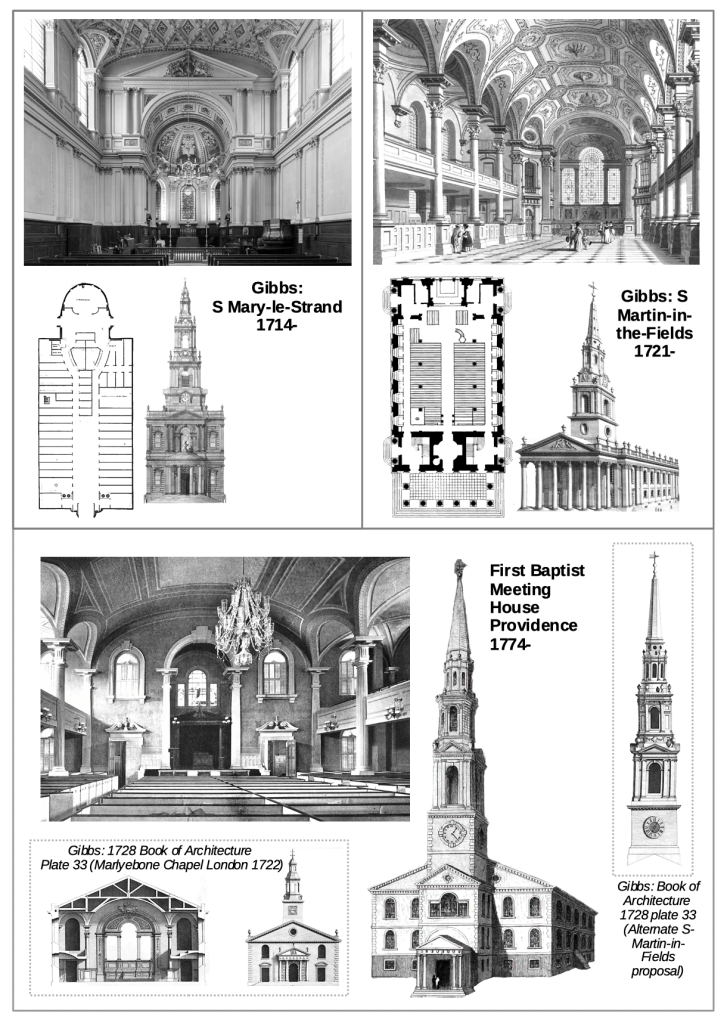

The James Gibbs Style

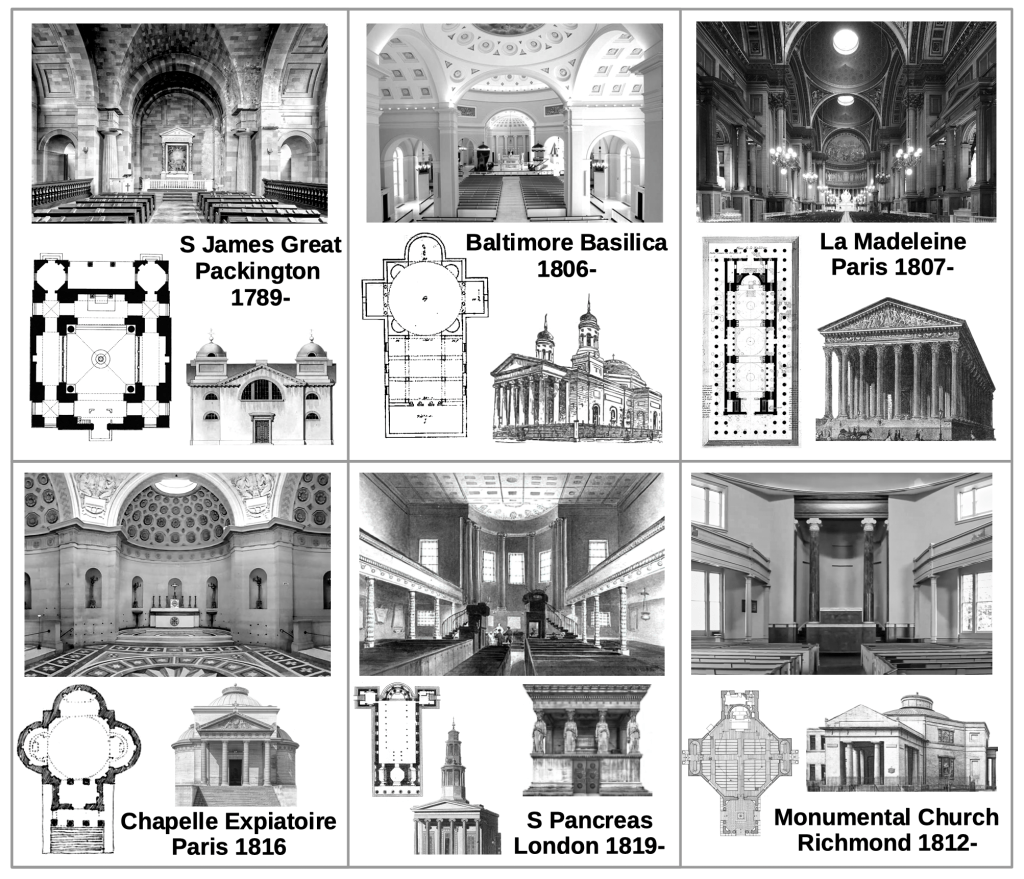

The Neoclassical Church

Leave a comment