Early Christian

Before Christianity reached Ireland in the 5th century, Celtic communities lived in circular houses of mud, thatch, or wood. The first Christian monks adopted this style, living in circular thatched huts like the replica at the Irish National Heritage Park. On Skellig Michael, where wood was less available, they created distinctive stone “beehive huts.”

St. Patrick likely introduced rectangular churches to Ireland. The earliest versions, built of wood or mud, have not survived, but they probably resembled later stone churches such as 10th-century St. MacDara’s. This small gabled structure features a trabeated doorway that narrows at the top, projecting side walls (antae), and corner finials. The slate roof imitates wooden shingle construction, showing how stone churches evolved from timber models. In the Munster region, early Christians developed unique tent-shaped stone churches. Gallarus Oratory is the best-preserved example of this style.

Round towers were added to monastic sites beginning in the 9th century. They may have been inspired by Italian conical towers of the 8th century, but their popularity in Ireland was likely a response to Viking raids. The doorways of these towers were built high above the ground. Ladders would be used to access the entrance and then pulled up in the event of an invasion.

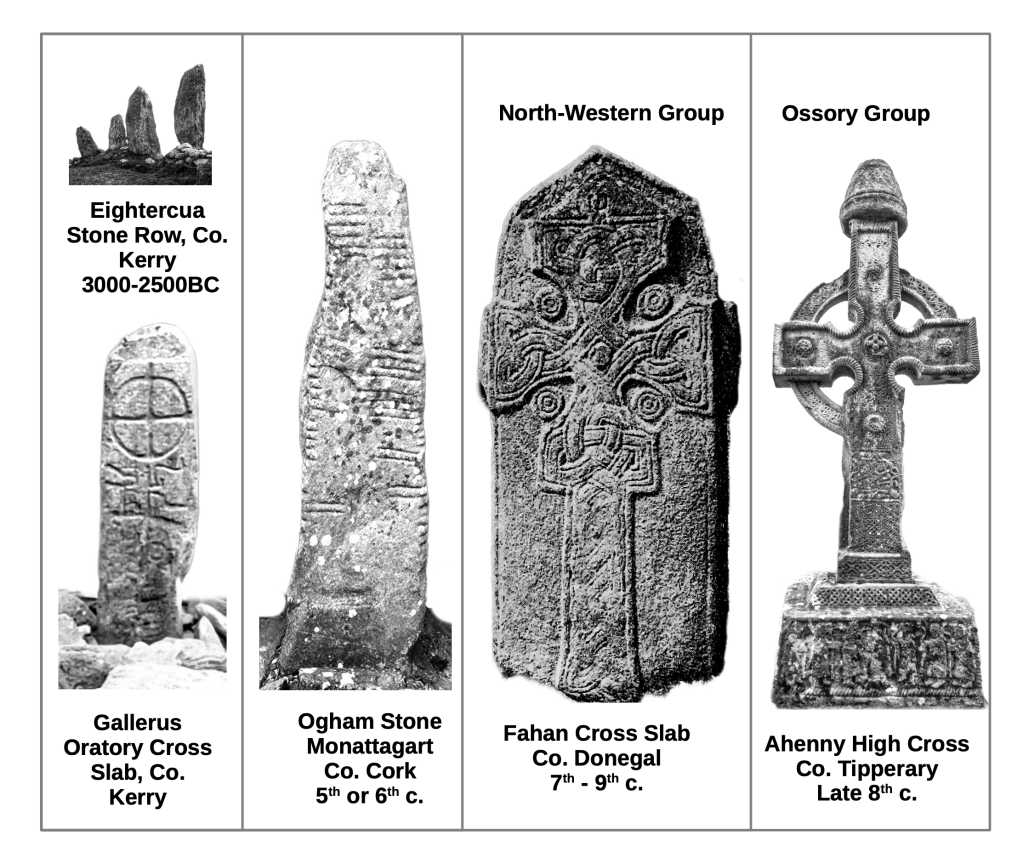

From Standing Stones to Celtic Crosses

Early Irish church buildings were plain and functional, but Irish artisans developed a decorative style known as “insular.” This style, first used in manuscripts and metalwork, was applied to tall stone crosses erected near churches. The exact purpose of these crosses is unknown, but they may have continued an older tradition of standing stone monuments, which in Ireland stretched back to the stone circles of the Neolithic period. Pre-Christian Celts also set up tall commemorative pillars known as ogham stones. These bore inscriptions in a notched code that recorded the names of victors in battle. When Christianity arrived, similar standing stones appeared with engraved crosses, such as the 7th-century cross-in-circle slab at Gallarus Oratory and the ornate Fahan Cross Slab.

The insular style originated in Celtic metalwork, famous for its complex interlace patterns. The Ahenny High Cross, dating to the late 8th century, is the earliest complete example of the “High Cross” form. Its features suggest it was modeled on a wooden processional cross once covered with decorated metal plates.

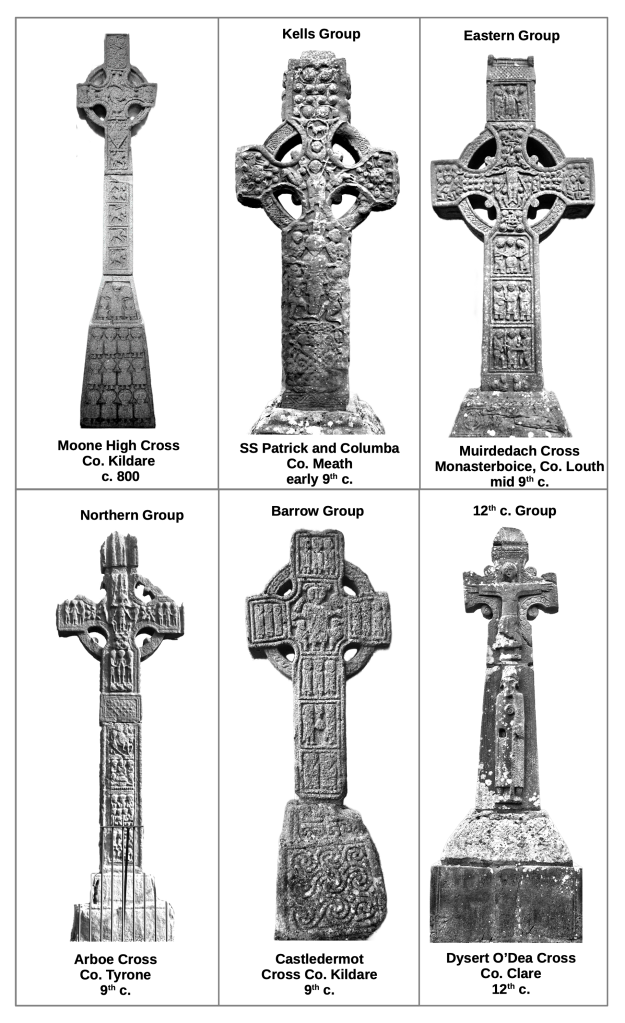

Over the course of the 9th century, High Crosses became widespread and developed regional variations. Sculptors began carving biblical stories onto the panels, turning the crosses into teaching tools for illiterate communities. The tradition continued into the 12th century, when the figures became larger, more detailed, and more naturalistic, as seen on the High Cross at Dysert O’Dea.

Early 12th Century Proto-Romanesque

With the exception of the richly decorated High Crosses, early Irish church buildings remained plain and undecorated well into the 12th century. There are a few exceptions. White Island preserves a series of unusual stone carvings at a monastery from the 9th or 10th century. St. Feichin’s 10th-century church has a simple cross-in-circle inscription, and Maghera Old Church (11th century) displays a crucifixion scene carved over its doorway.

In the early 12th century, the church layout was expanded. The traditional rectangular form was modified by opening a large arch in the east wall and adding an extended chancel. Surviving early examples include Temple MacDaugh and Reefert’s Church.

By this time, the Romanesque style had already flourished on the continent for more than a century. It reached Ireland only in the early 12th century, where it was adopted cautiously at first. The windows at Banagher Church, outlined with simple mouldings, represent one of the earliest experiments. Aghowle Church shows further development with a prominent stone moulding surrounding its trabeated doorway and a window framed by rudimentary columns. At St. Caimin’s, the chancel arch incorporates clustered columns—one of the first fully realized examples of a Romanesque motif in Ireland.

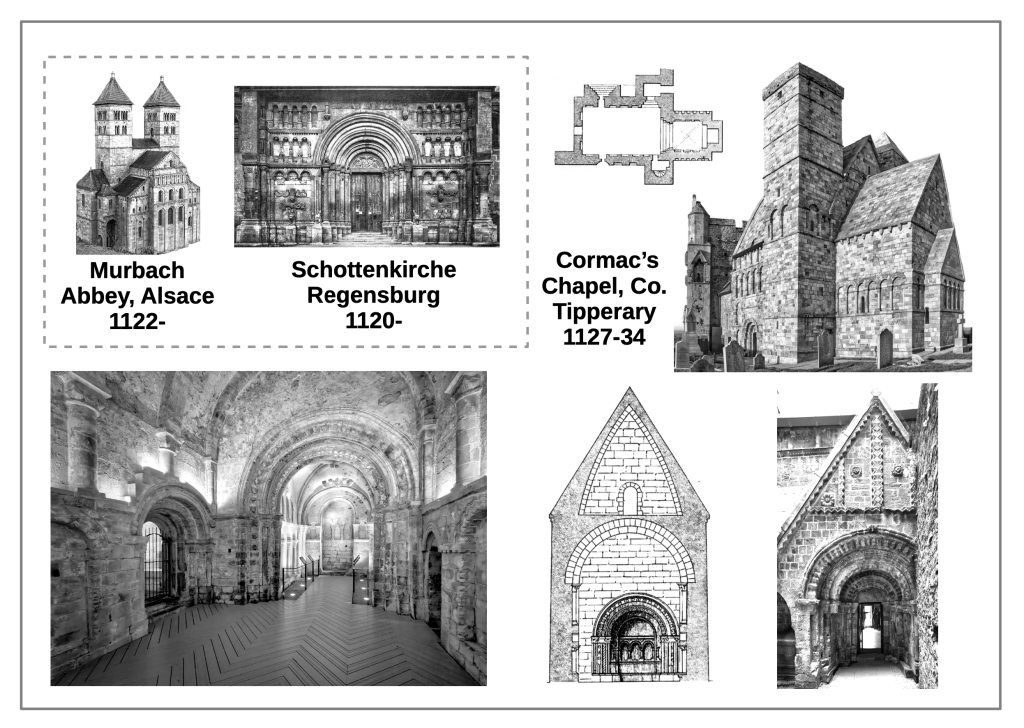

Cormac’s Chapel

Cormac’s Chapel, built in the 12th century at Cashel, is Ireland’s only fully realized Romanesque church. In keeping with continental prototypes, it includes two flanking towers, a chancel extension, barrel vaulting, richly decorated archivolts, and rows of arcades both inside and out. Its design may reflect influence from churches at Murbach and Regensburg, where Irish monks had ties with German counterparts. Yet unlike continental examples, Cormac’s Chapel remained small in scale, windowless, and without a transept.

Cormac’s chapel introduced two architectural features that spread widely in Irish churches of the period: the gabled arch and the barrel-vaulted nave topped by a steeply pitched attic story. The gabled arch is likely a stone version of an original wooden gabled porch.

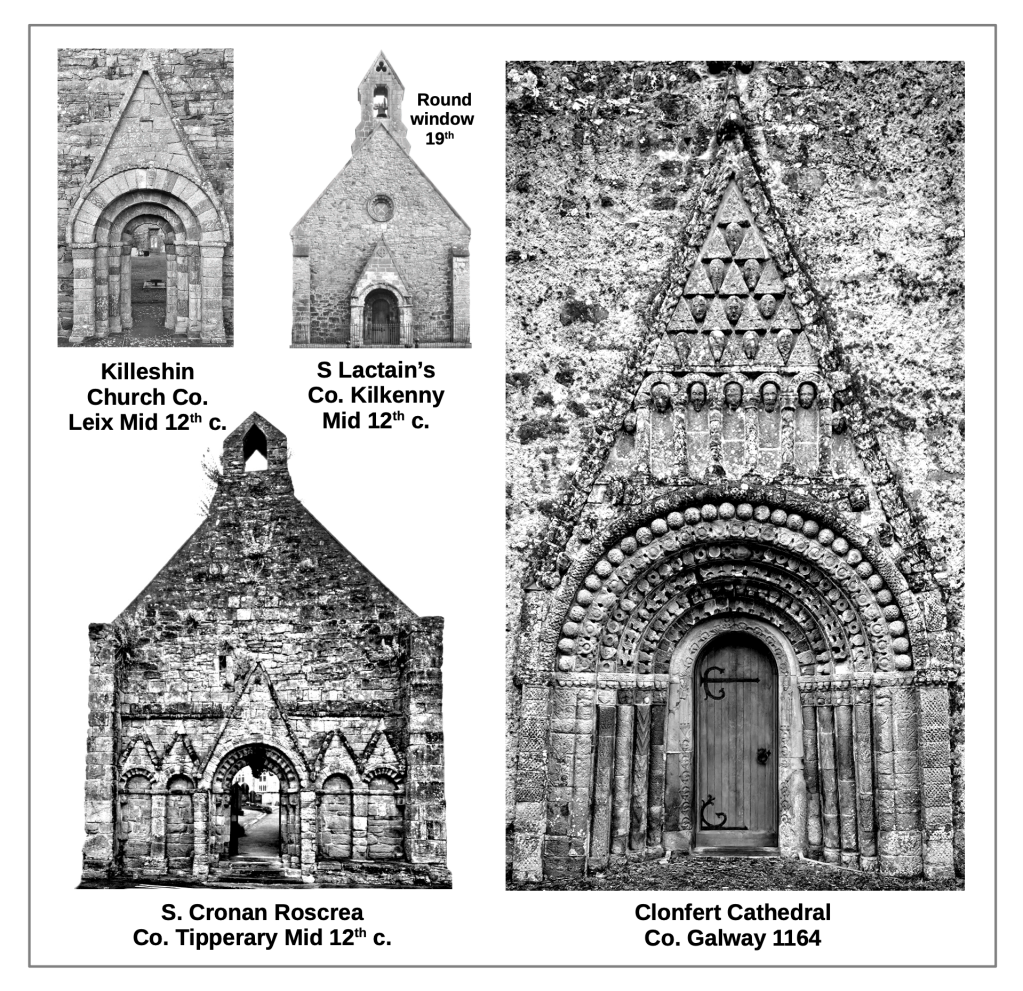

The Hiberno-Romanesque Gabled Arch

During the 12th century, Irish builders developed a distinctive form of Romanesque known as Hiberno-Romanesque. The name derives from Hibernia, the Roman term for Ireland, and distinguishes the style from English and continental variations. Its most characteristic feature is the rounded arch crowned by a triangular gable, likely inspired by the gabled arch at Cormac’s Chapel.

The style reached its zenith at Clonfert Cathedral (1164), whose west doorway is the most richly decorated example of a gabled arch in Ireland. Elaborate carvings fill the archivolts, and a pattern of sculpted heads alternating with triangles fills the gable. The columns at Clonfort lean slightly inward, narrowing toward the top, which suggests that the doorway was superimposed on an earlier trabeated entrance built in the traditional Irish manner. St. Cronan’s Chapel also showcases the form, with an entire row of gabled arches, although without Clonfert’s sculptural richness.

Despite these decorative innovations, Hiberno-Romanesque churches retained the simple outlines of earlier Irish buildings. Their facades were still framed by projecting antae, a feature first seen at St. MacDara’s 10th-century church (figure 1).

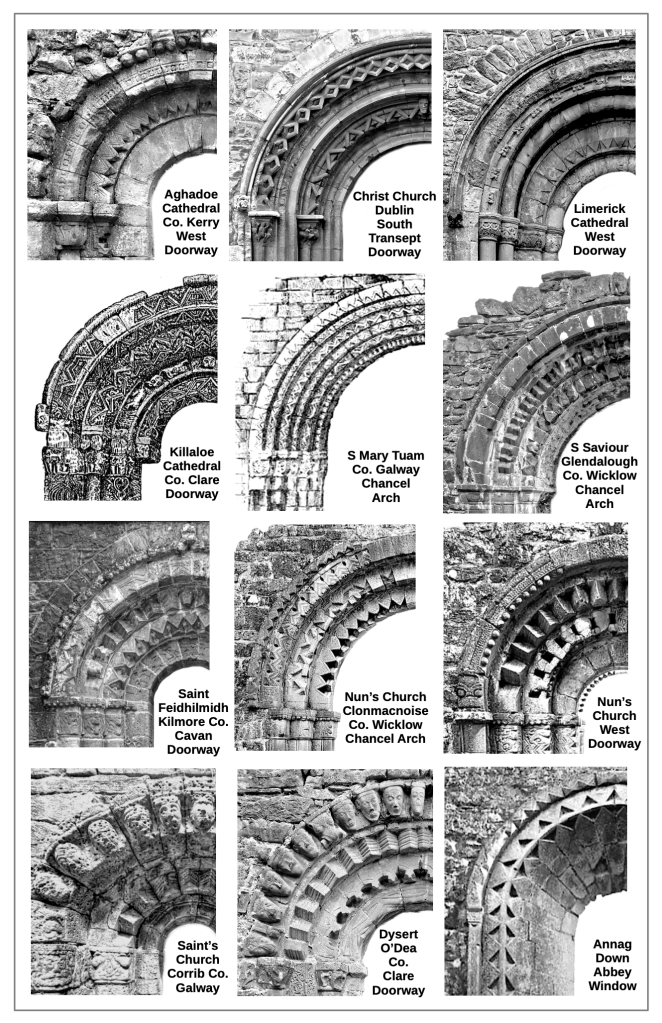

12th Century Romanesque Archivolts

Although Hiberno-Romanesque churches often retained plain walls and simple layouts, their doorways and chancel arches displayed an extraordinary richness of ornament, rivaling continental examples. These arches were carved with a wide range of motifs, including chevrons (zigzags), lozenges (diamond shapes), beading, and sculpted human or animal heads.

The decoration combined influences from abroad with native traditions. High-relief geometric patterns, such as the bold chevrons at Dysert O’Dea, reflect the influence of Anglo-Norman Romanesque in England. At the same time, flat surfaces were often filled with low-relief carvings—vegetal, geometric, or interlace patterns. This finer work grew directly out of Ireland’s insular art tradition, already seen in the decoration of earlier High Crosses.

Other Romanesque Examples

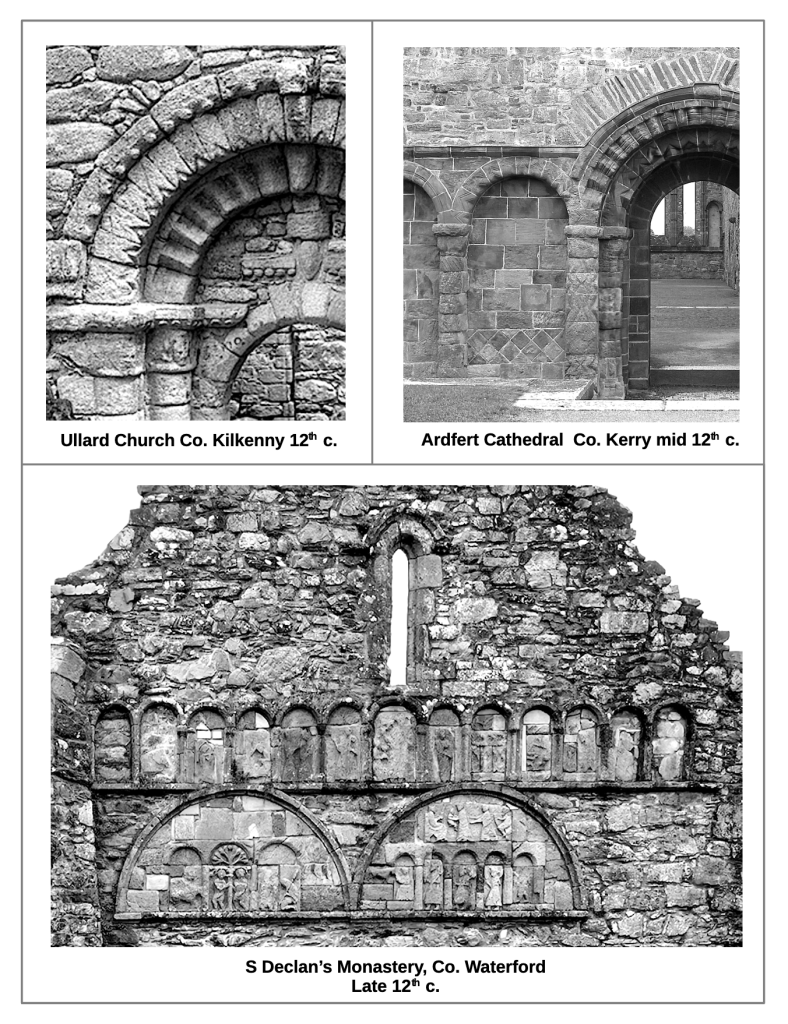

The three churches illustrated above contain unusual iterations of the Romanesque style. Ullard church features a strange lower arch supporting the upper archivolts. Ardfert Cathedral’s west doorway is flanked by an arcade, a rarity in Ireland, though more common in continental Romanesque examples. St. Declan’s monastery contains a strange set of arcades on its west end depicting various figures and events from the Bible.

Irish Cistercian Monasteries

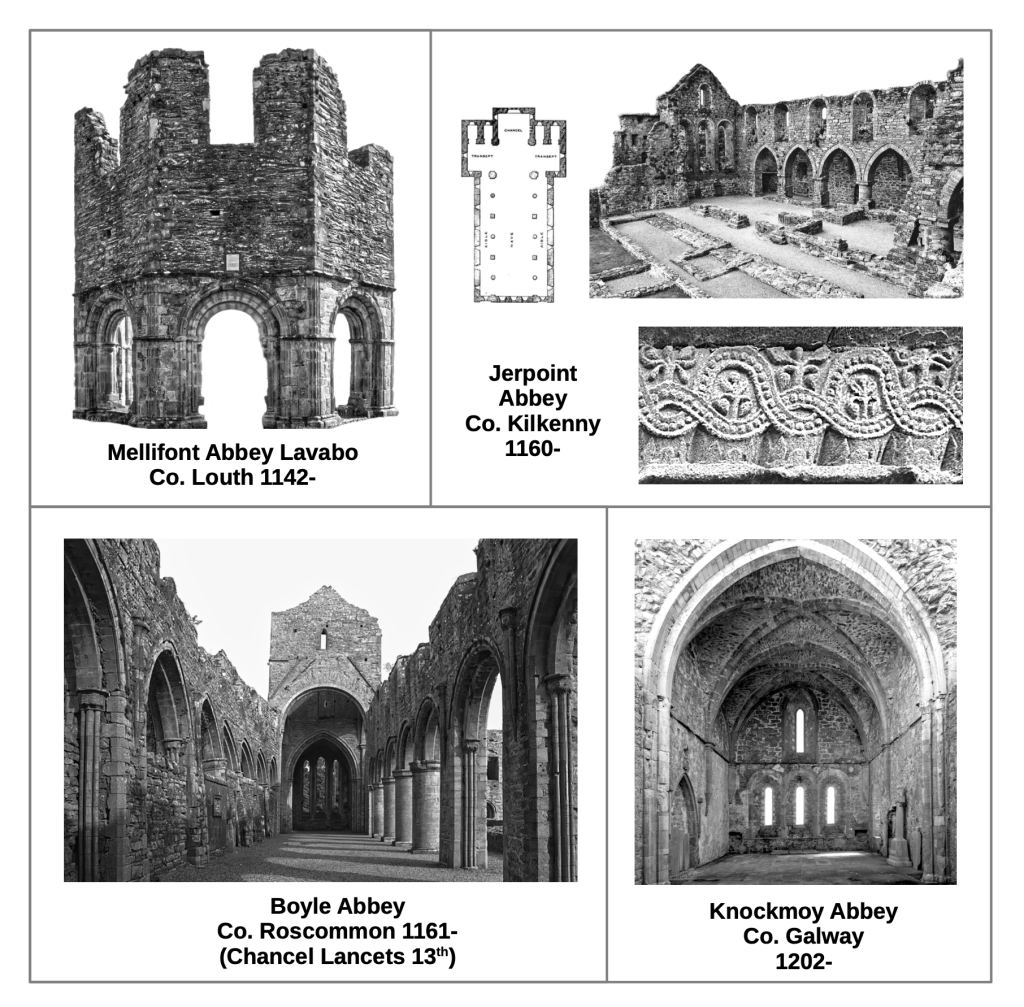

The Cistercian order, founded in 1098 in eastern France, spread rapidly across Europe and reached Ireland with the foundation of Mellifont Abbey in 1142. Mellifont housed the first Irish chapel with a full basilica plan: aisles flanking the nave, a clerestory above, transepts, and apses containing chapels. Although little of Mellifont survives today beyond its distinctive octagonal lavatory, its chapel floor plan was similar to the better-preserved one at Jerpoint Abbey.

Cistercian architecture is sometimes categorized as “transitional,” a bridge between the energetic muscularity of Romanesque, and the more refined and attenuated Gothic style. Transitional architecture retains the Romanesque style’s richly moulded round arches, although they are more streamlined and restrained in their ornamentation. Compare the delicate interlaced banding shown at Jerpoint in figure 9 to the jagged architraves illustrated in figure 8. The movement toward Gothic is even clearer at Knockmoy Abbey, which contains Ireland’s first ribbed vault and features a pointed chancel arch—elements that anticipate the fully developed Gothic style to come.

Norman Cistercian Monasteries

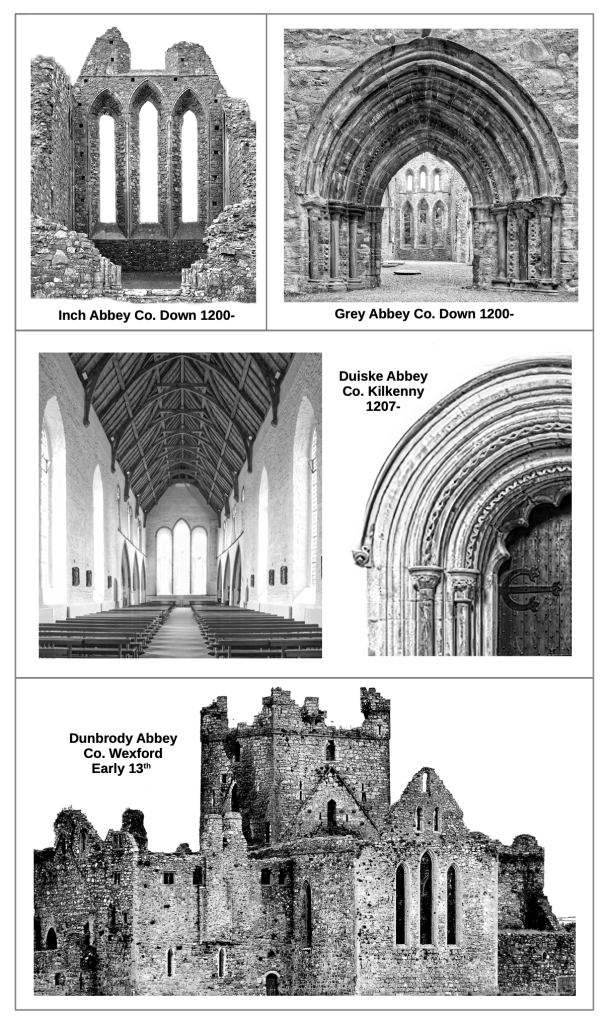

The Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 ushered in a new phase of Irish church architecture. Norman patrons established their own Cistercian foundations, closely modeled on English examples. Among the earliest are Inch Abbey and Grey Abbey, both founded around the year 1200. These abbeys were the first structures built in a fully Gothic style. Inch Abbey showcases a beautifully executed triple lancet window—an iconic feature of “Early English” Gothic. Lancet windows were soon adopted in monasteries and churches throughout Ireland, remaining in use long after their vogue had faded elsewhere in Europe.

Grey Abbey preserves one of the finest doorways of the period. Its pointed arch and finely carved columns clearly mark it as Gothic, yet Romanesque traditions linger in the nailhead mouldings between the shafts. The doorway shows striking parallels with those of Salisbury and Wells Cathedrals, which were being built at the same time. A similar blend of styles can be seen at Duiske Abbey, where thin Romanesque bands persist on an otherwise Gothic doorway. The innermost arch is adorned with Gothic cusps—a fashionable detail for the time.

Duiske Abbey is one of the few Cistercian churches in Ireland still functioning as a parish church today. By contrast, Dunbrody Abbey lies in ruin, but remains among the most complete and imposing of the medieval Cistercian foundations.

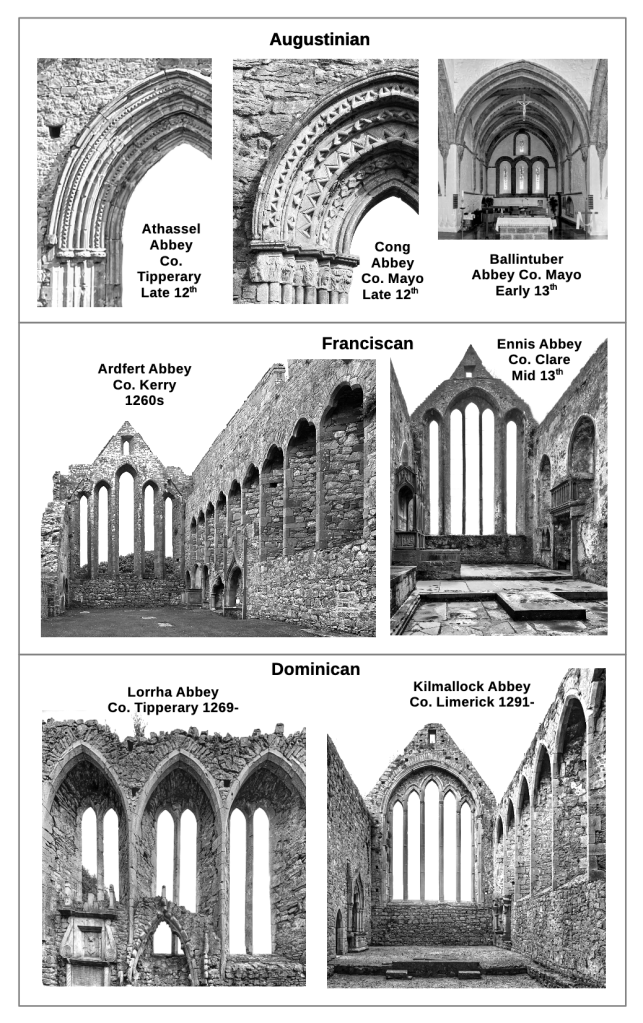

Augustinian, Franciscan, and Dominican Orders

In addition to the Cistercians, Ireland saw the establishment of Augustinian, Franciscan, and Dominican orders in the late 12th and 13th centuries. Unlike the architecturally uniform Cistercians, these groups built monasteries in a range of styles and floor plans. At Athassel Abbey and Cong Abbey, the transitional character of the period is evident in architraves where Romanesque ornament is applied to pointed Gothic arches. Ballintubber Abbey’s chancel, by contrast, closely follows the Cistercian model at Knockmoy. Ballintubber still functions as a parish church today and has preserved much of its medieval character.

By the mid and late 13th century, Franciscan and Dominican churches showcased the Irish preference for lancet windows, often arranged in groupings framed by large embrasures. Ennis Abbey displays three lancets within a single embrasure, Lorrha features paired double lancets repeated in sequence, and Kilmallock presents a dramatic set of five lancets within a single arched opening.

Unlike the Cistercian churches, many Augustinian and mendicant foundations were built without side aisles. Their windows were typically splayed—wide on the inside, but narrow on the exterior. Decorative details became more varied, as seen in the nave windows at Ardfert Cathedral, where the lancets are crowned with Gothic half rosettes.

The Great Dublin Cathedrals

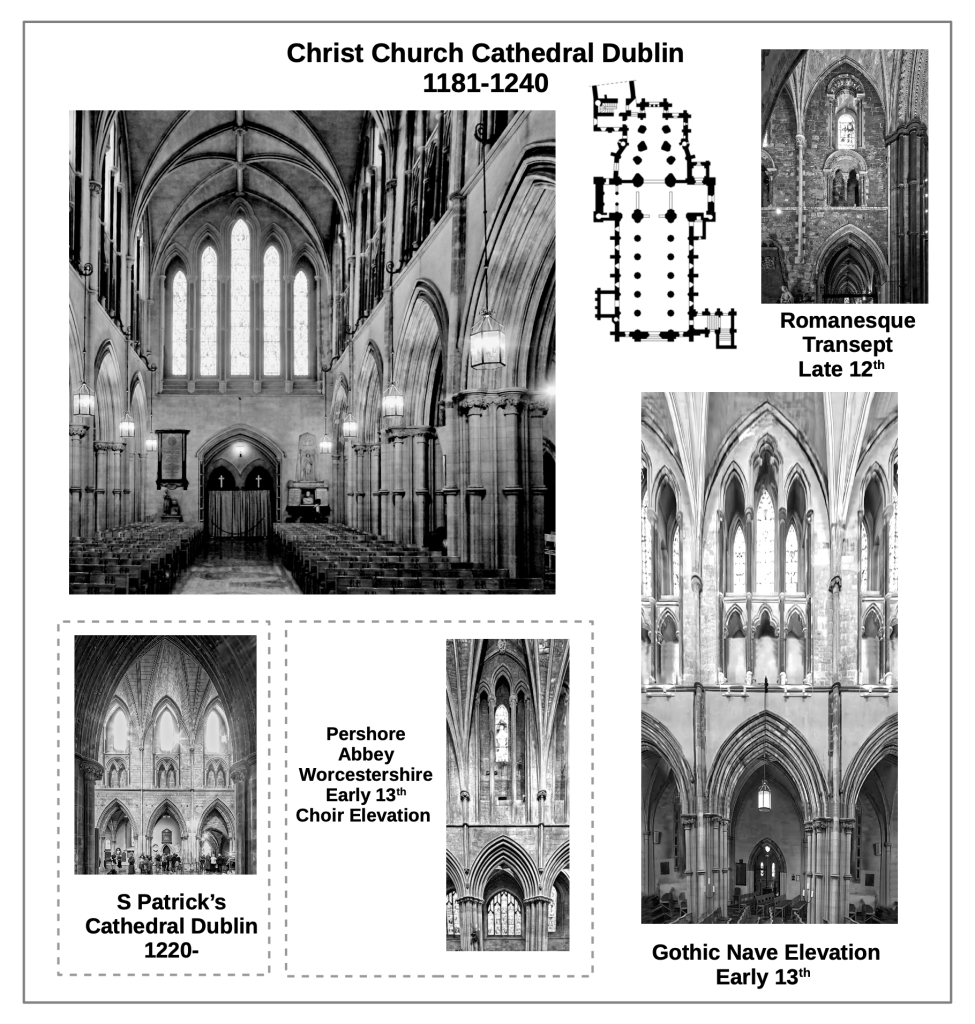

The arrival of the Anglo-Normans brought new wealth and influence to Dublin, leading to the construction of Ireland’s two great medieval cathedrals: Christ Church and St. Patrick’s.

At Christ Church Cathedral, the transept begun in 1181 still reflects the late Romanesque style, with rounded arches and bold chevron ornament. The nave, rebuilt in the 13th century, shifts to the Early Gothic style and shows clear affinities with Pershore Abbey in England. Yet the comparison is not straightforward. Pershore’s elevation lacks a triforium, while at Christ Church both the triforium and clerestory are present—but integrated into a single vertical scheme supported by shared columns. This arrangement anticipates the architectural unification of triforium and clerestory explored in French Rayonnant Gothic at Reims Cathedral, but is virtually unknown in the Early English Gothic tradition to which Christ Church otherwise belongs.

By contrast, the elevation at St. Patrick’s Cathedral is far more typical of the Early English style, with a clearly separated triforium and clerestory. The unusual integration at Christ Church may have arisen from the architects’ attempt to emulate Pershore’s long clerestory windows. Because they also wished to include a triforium, they disguised it within what looks like an extended clerestory zone.

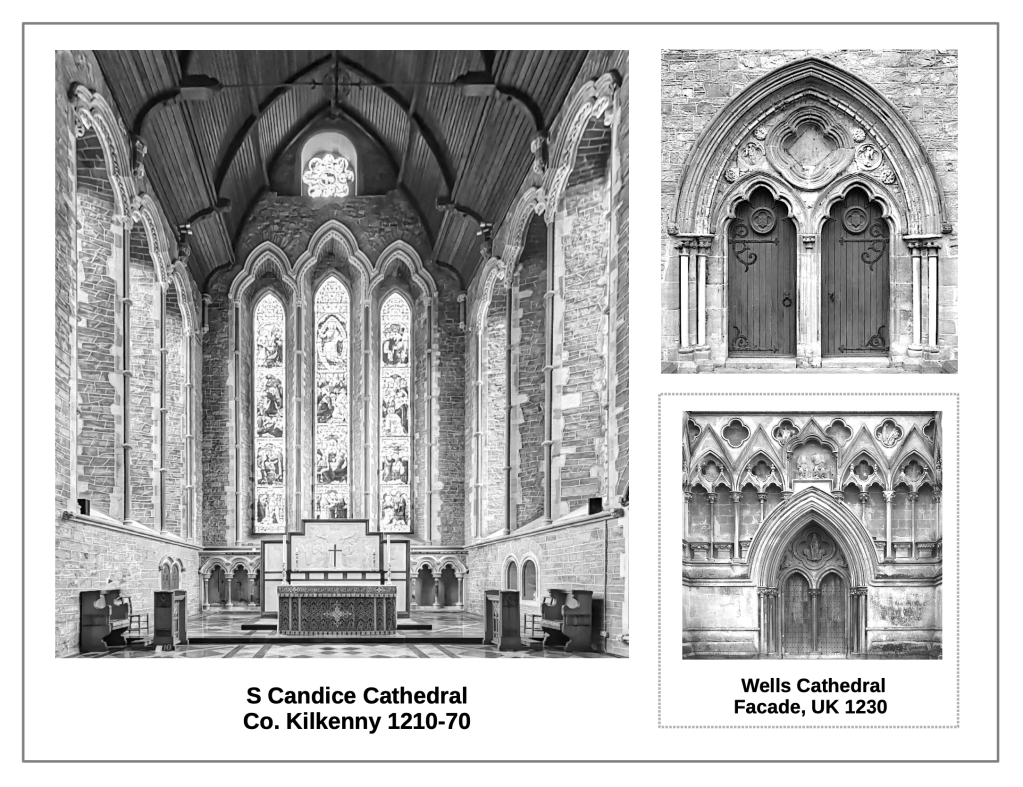

Decorated Gothic: St. Candice Cathedral

St. Canice’s Cathedral marks the transition from the Early English Gothic style, characterized by simple lancet windows, to the more elaborate Decorated Gothic style, which emphasized geometric groupings of windows. Construction began with the chancel in 1210, featuring a trio of lancets topped with half-quatrefoil motifs.

The cathedral’s western doorway, completed later, illustrates the more fully developed Decorated Gothic style. It consists of two arched doorways surmounted by a complete quatrefoil set within a larger Gothic arch. This composition closely parallels the designs on the facade at Wells Cathedral, suggesting direct influence from English models.

The Evolution of Gothic Tracery

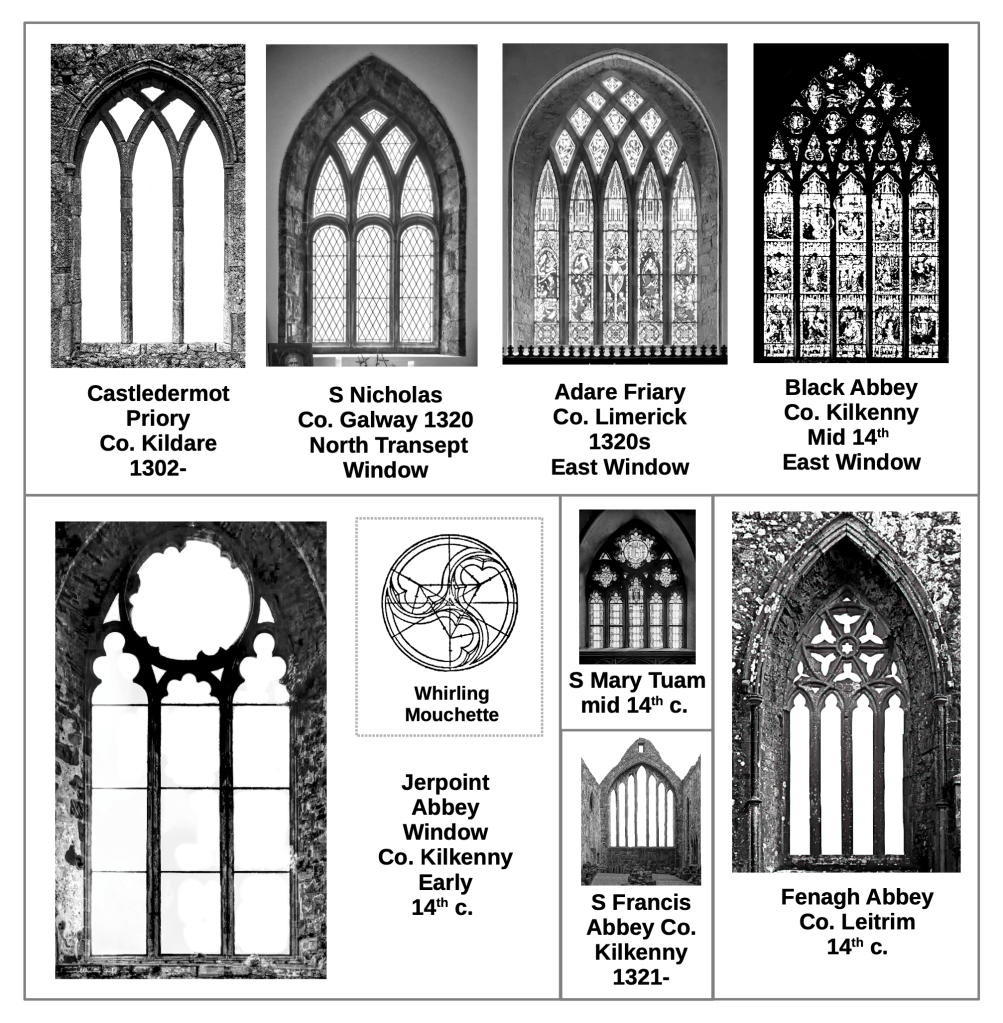

Intersected-line tracery began to appear in Ireland during the 14th century. Early examples can be seen at Castledermot Priory and St. Nicholas’ Collegiate Church. By the 1320s, more elaborate versions emerged, as at Adare Friary.

By the mid-14th century, Irish masons began enriching tracery with Decorated Gothic motifs, including cusps and quatrefoils. These can be seen at Black Abbey, St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tuam, and Fenagh Abbey. The east window at Jerpoint Abbey once contained what was probably a whirling mouchette—one of the more elaborate forms of Decorated tracery in Ireland.

Yet even as tracery developed, the older Gothic idiom persisted. Many churches continued to favor the simpler 13th-century lancet style, as at St. Francis Abbey (1321–).

From Decorated to Flamboyant Gothic

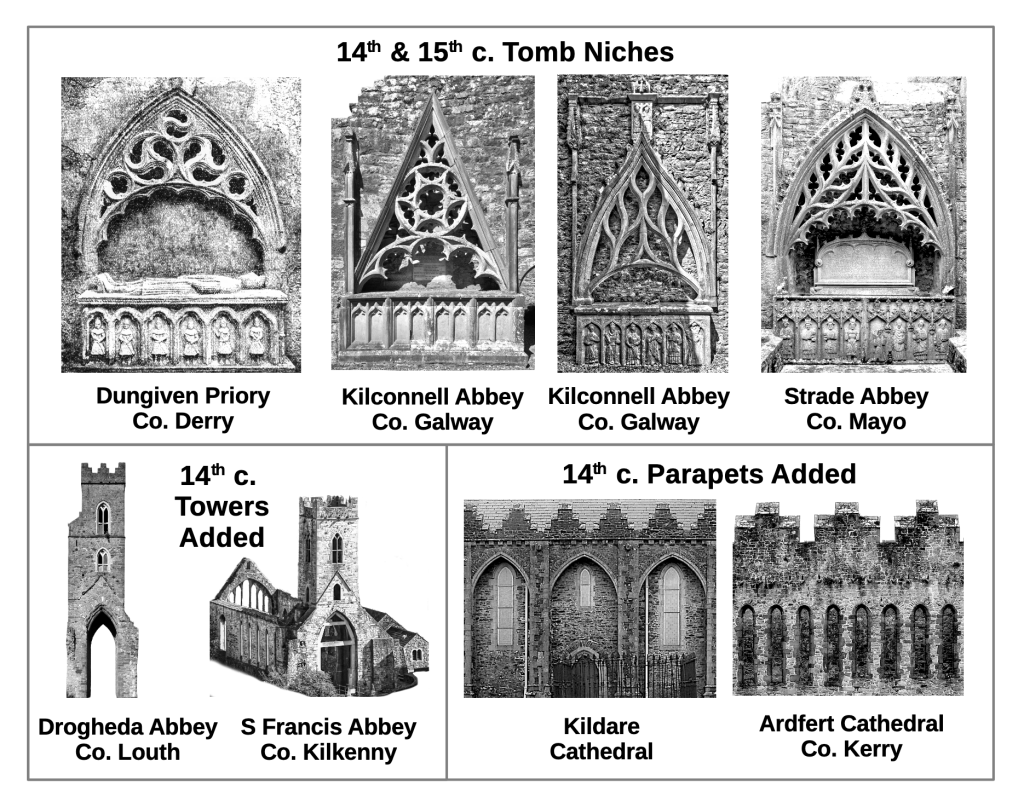

Some of the most striking examples of Irish Gothic tracery survive in 14th- and 15th-century tomb niches. At Dungiven Priory, the niche displays a graceful series of whirling mouchettes, while at Kilconnell Friary one niche uses assertive geometric forms and another adopts the “flamboyant” style, with tracery radiating in flame-like curves. The tomb niche at Strade Abbey combines elements of the geometric Decorated and fluid flamboyant styles.

Alongside these advances in tracery, the 14th century also saw the rise of belfry towers, as at Drogheda Abbey and St. Francis Abbey. These towers often carried stepped parapets. Some scholars suggest that this motif may have been introduced by Irish pilgrims returning from Santiago de Compostela, where they encountered similar forms in Catalan architecture.

15th Century Developments

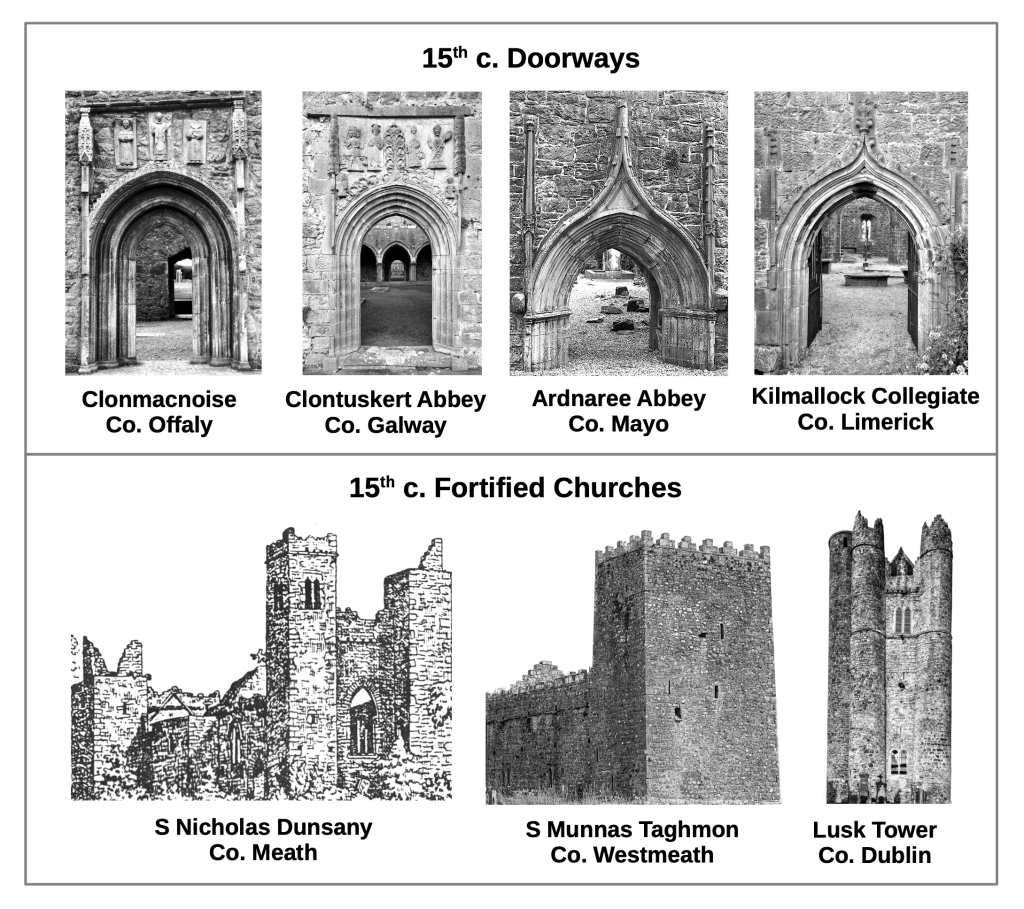

In the 15th century, Irish churches began incorporating ogee-arched doorways, a hallmark of late Gothic design. Some of the most exuberant examples appear at Clonmacnoise and Clontuskert Abbey, where the arches are crowded with sculptural decoration. More restrained versions survive at Ardnaree and Kilmallock, where the ogee arch is presented in its prototypical form.

This period also witnessed a trend toward increasingly fortified, castle-like churches, especially in regions beyond the Pale— outside the English controlled areas of Ireland—which were subject to frequent raids. These churches often incorporated defensive towers and heavy masonry, blurring the line between sacred and military architecture. St. Munna’s is among the most striking of these fortified churches. Tradition holds that one parish priest even barricaded himself in its tower, lowering a basket by rope and refusing to descend until parishioners had filled it with offerings for mass.

15th Century Late Gothic Restorations and Additions

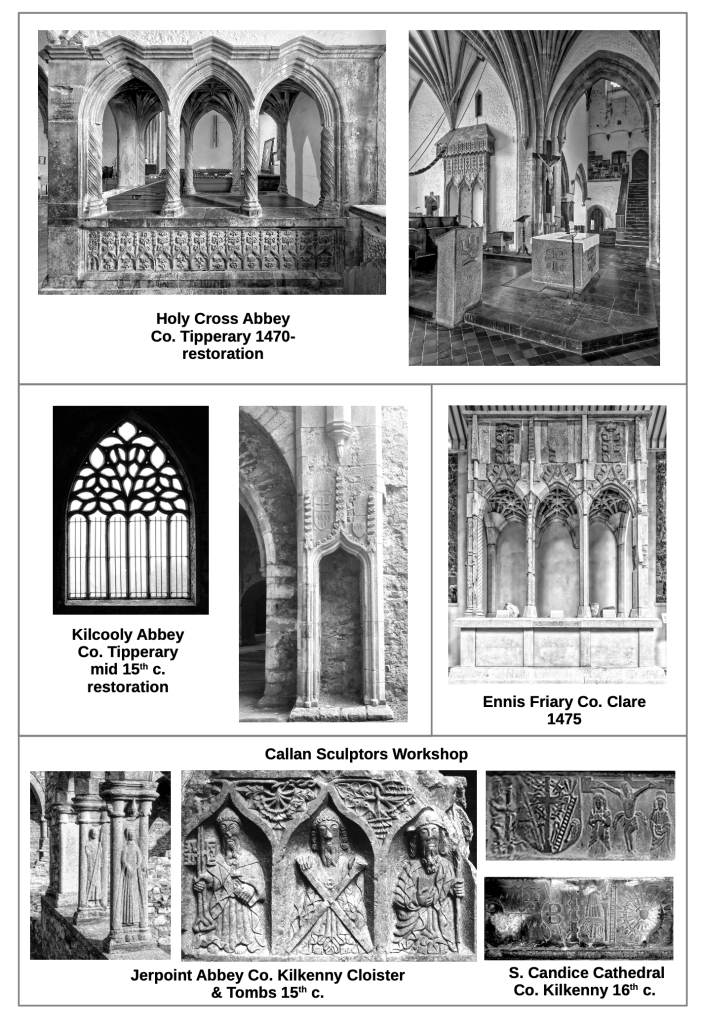

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the wealth and influence of the medieval church were in decline, while the power of the urban merchant class was on the rise. Few entirely new churches were built during this period, but private donors funded a range of restorations, remodels, and tombs that gave existing churches new life.

One of the finest examples is the 15th-century restoration of Holy Cross Abbey, which introduced a richly vaulted chancel, an elaborate sedilia, and the enigmatic “monk’s walk”—a platform supported by spiraled columns. These columns embody the late Gothic ideal of organic verticality, rising uninterrupted from floor to ceiling like tree trunks in a forest, without the breaks of capitals or string courses.

At Kilcooly Abbey, a remodeled Gothic window suggests an attempt at flamboyant tracery like that found in the tomb niches of Kilconnell and Strade, but the design instead settles into a distinctive floral pattern. Kilcooly also added a finely carved sedilia. Ennis Friary preserves a richly vaulted Gothic tomb.

Much of the finest carving of the 15th and 16th centuries came from a sculptors’ workshop in Callan. Their work at Jerpoint Abbey and St. Canice’s Cathedral represents a high point of Irish Gothic craftsmanship. In the Butler tombs at St. Canice’s (16th century), the Callan sculptors pioneered a freer, more narrative style of figural carving, moving away from the rigidly compartmentalized niches of earlier tomb design. This artistic development hinted at a new direction for Irish sculpture, one that was abruptly cut short by the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-16th century.

15th to 16th Centuries: Late Gothic Monasteries

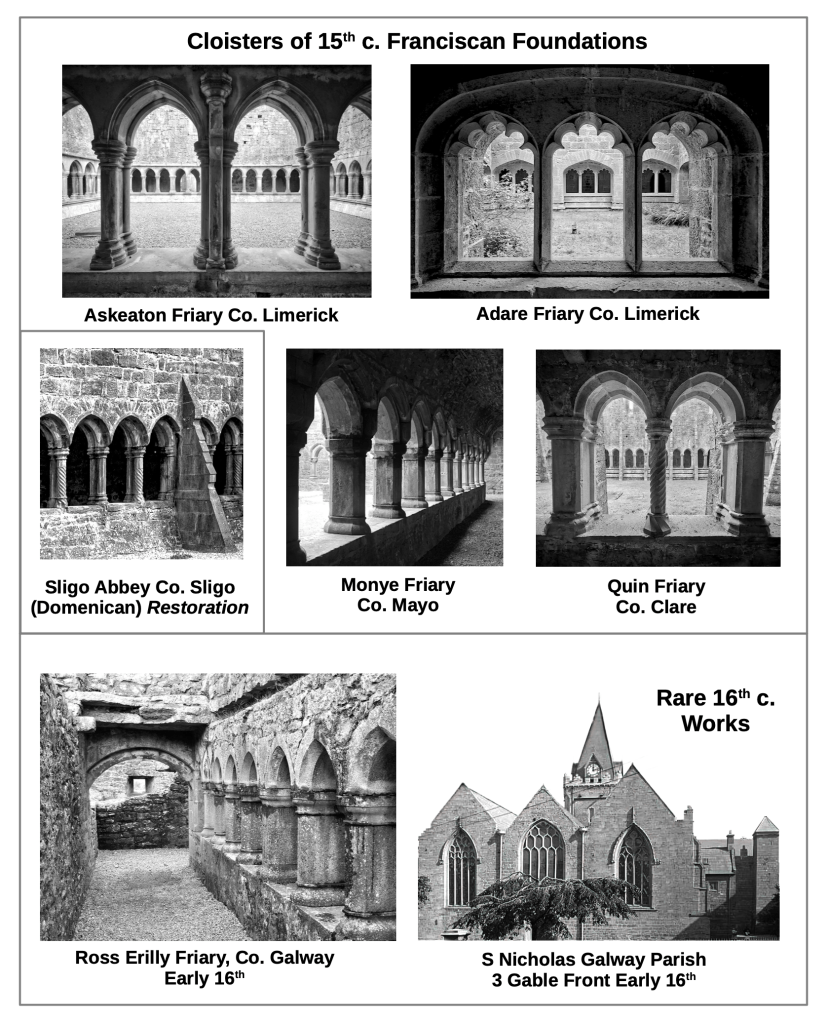

On the eve of the Protestant Reformation, Ireland experienced one final wave of monastic construction. The Franciscan order, enormously popular in the 15th century, admitted both Irish and Anglo-Irish monks and had the wide support of lay communities. The new Franciscan establishments were more modest than the great monasteries of earlier centuries, but they preserve some of the finest cloisters in Ireland. At Sligo and Quinn, the cloisters even include spiral—or Solomonic—columns.

In the 16th century, one of the last major medieval building projects was the expansion of St. Nicholas’ Collegiate Church in Galway. Two vast aisles were added on either side of the nave, each nearly the same size as the central vessel, creating a striking triple-gabled facade that soon became a civic emblem of Galway. The Convent of Mercy was built in Galway in 1840 and included a similar triple-gabled front as a tribute to St. Nicholas’ Collegiate.

This last flowering of Irish Gothic was short-lived. With the Protestant Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-16th century, church building came to an abrupt halt. What survives today is a layered record of adaptation and innovation, where native forms, continental influences, and local patronage combined to create a distinctive strand of medieval architecture.

Photo Credits

Most of the photos in these figures are taken from wikimedia commons and have been released under Creative Commons BY 4.0. When I could not find open access images, I lifted them from google map contributors, personal blogs, or travel websites. Please contact me if you have any concerns about my use of your image.

Figure 1: Irish Monastic Hut (zairon), Gallerus Oratory (Ingo Mehling), Skellig Michael (Rob Burke), St. MacDara’s Church (stamp image), Round Tower (ClipArt ETC).

Figure 2: Eightercua (Niall Huggard), Gallerus Standing Stone (Philip Halling), Ogham Stone (author), Fabian Cross Slab (Internet Archive Book Images), Ahenny High Cross (Maureen Maher)

Figure 3: Moone High Cross (author), Kells (author), Muirdedach (author), Arboe (motorhomewanderings), Castledermot (author), Dysert O’Dea (author)

Figure 4: White Island (Jason098), St. Fechin’s (author), Maghera (NI.gov), St. Caiman’s (SteveFE), Temple MacDuagh (Ronan Mac Giollapharaic), Reefert (author), Banagher (megalithicireland.com), Aghowle 1 (Andreas F. Borchert), Aghowle 2 (Andreas F. Borchert)

Figure 5: Murbach (Moleskin), Schottenkirche (postcard), Cormac’s Chapel exterior (Warren Le May), interior (author), gabled entrance (author), illustration (Sir Banister Flight Fletcher.

Figure 6: Killeshin (author), St. Lactain (A.-K.D.), St. Cronan (author), Clonfort (author).

Figure 7: Aghadoe (author), Christ Church (author), Limerick (author), Killaloe (Clare Library), Tuam (National Library of Ireland), St. Saviour (author), Fethilmidh (Olliebailie), Nun’s Church (Matt Woods), Clonmacnois (public domain), St. Corrib (Werna-Marie Naude), Dysert O’Dea (author), Annaghdown (Brian Dornan)

Figure 8: Ullard (kevin higgins), Ardfert (GordonPin), St. Declan 1 (author), St. Declan 2 (author).

Figure 9: Mellifont (author), Jerpoint 1 (Zairon), floorplan (archiseek.com), frieze (irelandhighlights.com), Boyle (Andreas F. Borchert), Knockmoy (angelfire.com).

Figure 10: Inch (author), Grey (author), Duiske 1(Smirkybec), Duiske 2 (Mike Searle), Dunbrody (August Schwerdfeger).

Figure 11: Athassel (Andreas F. Borchert), Cong (Andreas F. Borchert), Ballintuber (Sarah V.), Ardfert (Andreas F. Borchert), Ennis (author), Killmallock (Einaz80).

Figure 12: Nave (zairon), Transept (author), floorplan (public domain), St. Patrick’s (author), Pershore (Philip Pankhurst), Elevation (author).

Figure 13: St. Candice chancel (Twasonasummersmorn), St. Candice door (Patrick Wyse Jackson), Wells (Rodw).

Figure 14: Castledermot (author), St. Nicholas (author), Adare (author), Black Abbey (antony-22), Jerpoint (Michael Raj Groves), Mouchette (public domain), Tuam (Karen Duignan), St. Francis (Eirian Evans), Fenagh (Christopher Conferee).

Figure 15: Dungiven (book image archive), Kilconnell 1 (author), Kilconnell 2 (author), Strade (Andreas F. Borchert), Drogheda (author), St. Francis (Zairon), Kildare (A.-K.D.), Ardfert (Zairon).

Figure 16: Clonmacnoise (Neuköllner), Clontuskert (author), Ardnaree (Andreas F. Borchert), Killmallock (author), Dunsany (Noel E. French), Taghmon (Bridget Neville), Lusk (author).

Figure 17: Holy Cross 1 (author), Holy Cross 2 (author), Kilcooly window (Digital Eye), Kilcooly (A.-K.D.), Ennis (author), Jerpoint 1 (Arie M. den toom), Jerpoint 2 (Gerd Eichmann) St. Candice (megalithicireland.com).

Figure 18: Askeaton (author), Adare (author), Sligo (Andreas F. Borchert), Monye (Andreas F. Borchert), Quin (author), Ross Erilly (author), S. Nicholas (National Library of Ireland)

Leave a comment