From the 17th to the 21st Centuries

With the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-16th century and the turbulence of the Reformation, Ireland’s long tradition of medieval church building came to an abrupt halt. The great Gothic churches and abbeys fell into ruin, and few new religious structures were erected in their place. What remained was often adapted for new purposes.

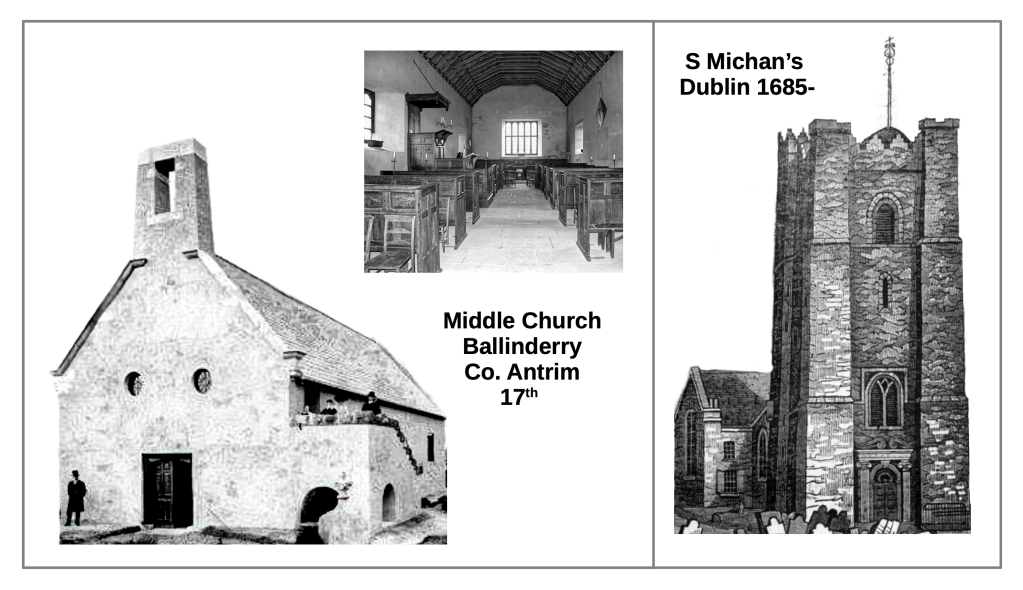

17th Century Survivals

One rare survivor from the 17th century is the Middle Church at Ballinderry, preserved largely in its original form. Still lit by candlelight, it offers a glimpse of 17th-century worship in the Church of Ireland. Inside, a side pulpit and oak box pews with attached candlesticks create an intimate atmosphere that captures the austerity and piety of the period.

The only other significant church surviving from the 17th is St. Michan’s in Dublin. Although its interior was substantially remodeled in the 18th century, the exterior tower survives unchanged. With its battlemented parapets, wall buttresses, and simple window tracery, it represents a modest instance of “Gothic Survival” architecture.

18th Century: The Influence of Christopher Wren

The first notable church built in Ireland after the Reformation was St. Mary’s on Mary Street, Dublin (now The Church Café). Its design reflects the influence of Christopher Wren, whose London churches, constructed after the Great Fire of 1666, set the model for late 17th and 18th century church architecture throughout the English-speaking world. Like many of Wren’s works, St. Mary’s includes a gallery—the first in Ireland—a feature that soon became standard in 18th- and early 19th-century churches. Though its woodwork was excellent by contemporary Irish standards, it did not quite match the refinement of the woodwork at Wren’s London churches.

Fifteen years later, St. Werburgh’s represented a clear step forward in quality. Its elegant classical front placed it firmly within the mainstream of Georgian design. The present interior, rebuilt in 1759 after a fire, is notable for its richly carved side pulpit, executed in a “high-Gothick” style.

Several other important early 18th-century churches—Lisburn Cathedral, St. Anne Shandon, and Moira Church—also drew from Wren’s London models. Each features a prominent brick tower with quoins and restrained classical detailing. Later additions gave Lisburn and Moira Gothic spires, but St. Anne Shandon still preserves its original stepped belfry, a modest attempt to mimic Wren’s more elaborate towers.

The influence of Wren’s successors is visible too. St. John’s Ballymore adopts the style of architect James Gibbs, incorporating a Palladian window and quoined surrounds—elements popularized by Gibbs’s influential Book of Architecture (1728).

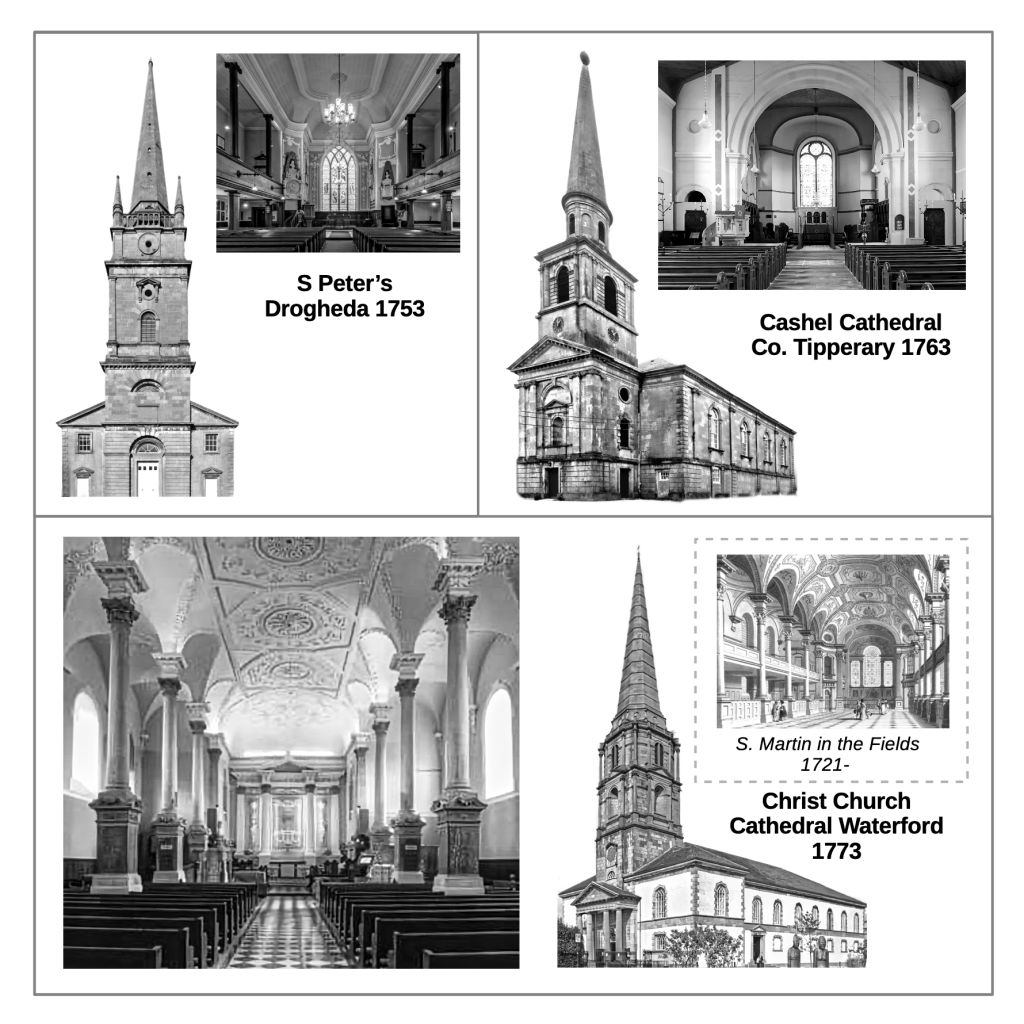

The Influence of James Gibbs

The writings of James Gibbs circulated widely in Ireland and left a strong imprint on mid- to late-18th-century church design. St. Peter’s Drogheda, though later altered with a Gothic Revival spire and east window, still shows Gibbs’s influence in the rounded chancel entrance, which closely recalls his design for the chancel at St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Two decades later, Christ Church Cathedral in Waterford drew even more directly from Gibbs’s vocabulary, incorporating sail vaults in the aisles—an innovation also seen at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. Cashel Cathedral’s interior has been heavily altered—much to its detriment—but the exterior preserves the noble proportions and steeple forms inspired by Gibbs’s designs.

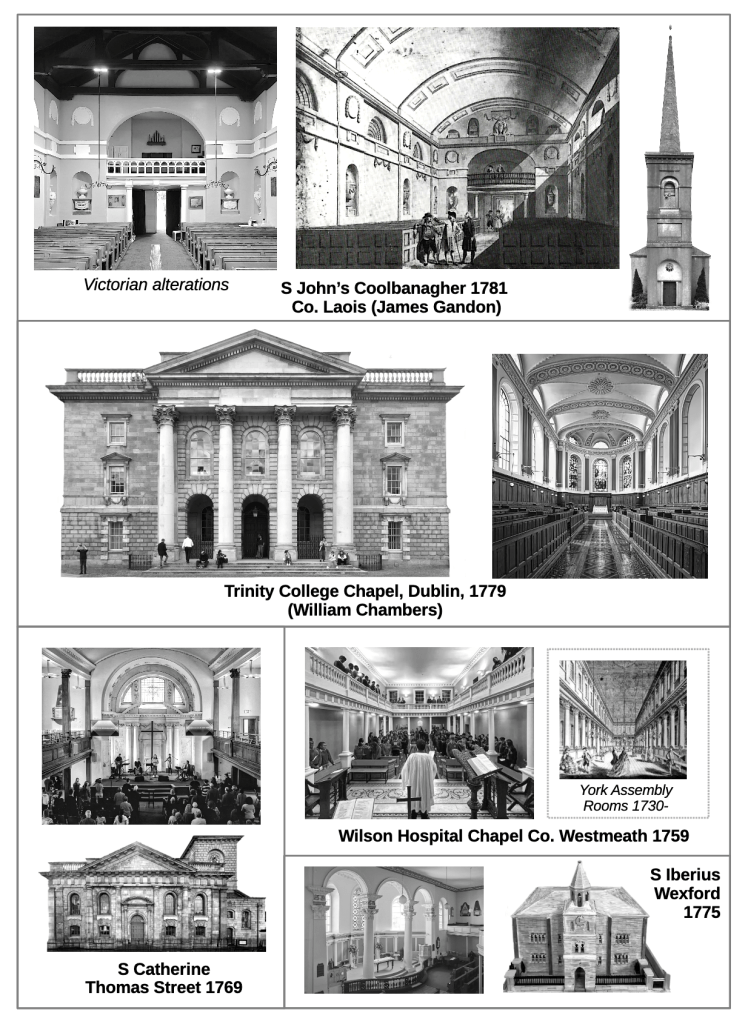

Late 18th Century Neoclassicism

While the churches of Wren and Gibbs represented the last flowering of the English Baroque, by the mid- to late 18th century a new architectural language had taken hold: neoclassicism. Unlike Baroque, which drew on the Italian Renaissance, neoclassicism looked directly to the ancient world for inspiration. It sought to embody ideals of reason, harmony, and civic virtue, producing buildings that were serene, rectilinear, and ordered. In Ireland, the leading exponents of this style were James Gandon and Sir William Chambers, whose influence shaped both civic and ecclesiastical architecture.

James Gandon, best known for Dublin’s Custom House and Four Courts, also designed the small chapel of St. James Coolbanagher. Though its barrel-vaulted ceiling was later replaced by a wooden one, the chapel still conveys Gandon’s sense of proportion and poise. William Chambers’ Trinity College Chapel exterior is a model of pure rectilinear neoclassicism. The interior blends styles, with groin vaults that recall the aisle vaults of Gibbs’s chapels. The Wilson Hospital Chapel’s design was inspired by Lord Burlington’s famous icon of neoclassicism, the York Assembly Rooms (1730-). At St. Catherine’s Thomas Street, the altar is framed by a broken pediment—a Baroque motif—but topped with a Diocletian window, a favorite of neoclassicists who borrowed it from ancient Roman baths.

St. Iberius, Wexford, wider than it is long, was built up against the city walls, forcing its architect to adopt an unconventional design. Freed from traditional constraints, the architect introduced an arcaded chancel that may have drawn inspiration from Gibbs-style nave columns (as at Waterford), but which ultimately resembles early Renaissance arcades like Brunelleschi’s Santo Spirito in Florence. Fittingly, its facade was rebuilt in 1882 in a neo-Renaissance style.

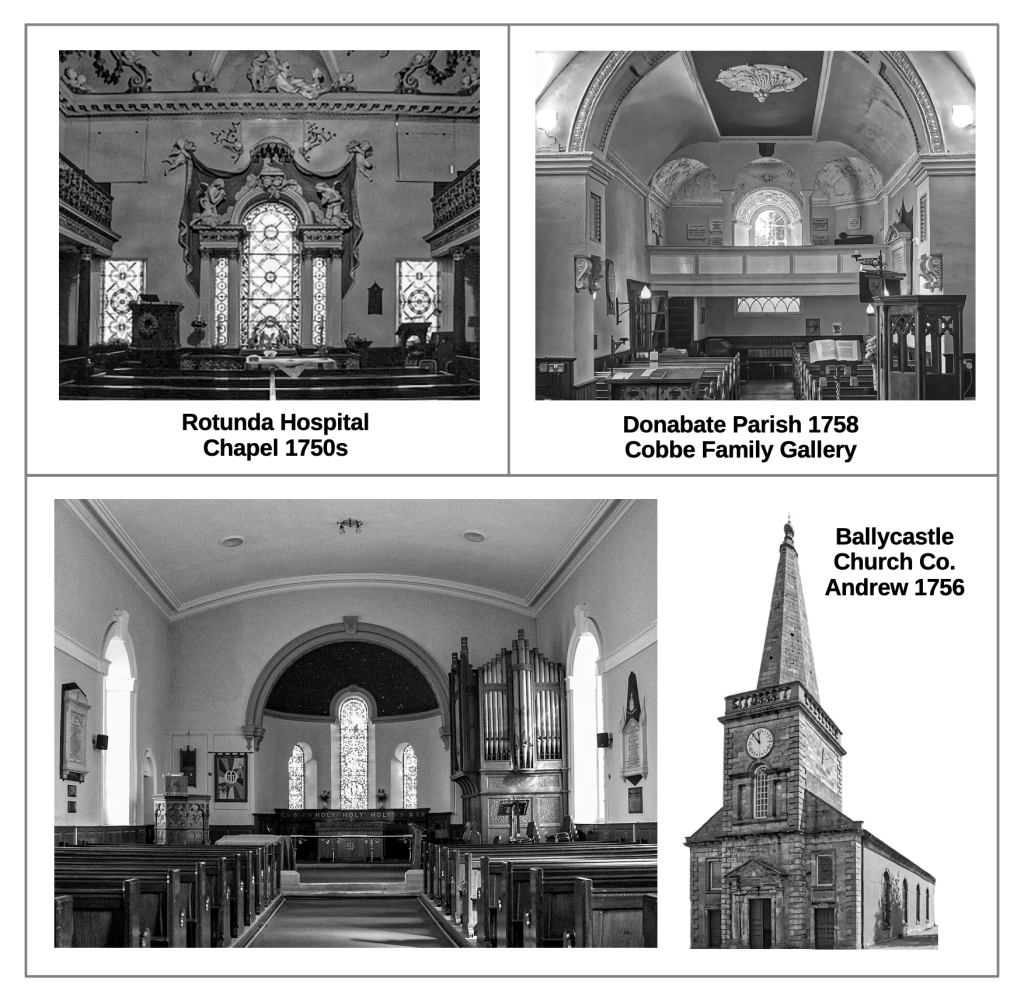

18th Century Landlord Chapels

The 18th century also saw the construction of a number of landlord chapels-small private churches built for estate owners and their tenants. Some of these chapels embraced the decorative exuberance of the Rococo style, as in the Rotunda Hospital Chapel and the Donabate Parish Chapel. Donabate is especially notable for the Cobbe Family gallery, lavishly stuccoed in swirling ornament, which contrasts to the plainer walls of the rest of the church.

The chapel at Ballycastle adopted a more restrained classical character, demonstrating the influence of neoclassical ideals of proportion and harmony rather than Rococo extravagance.

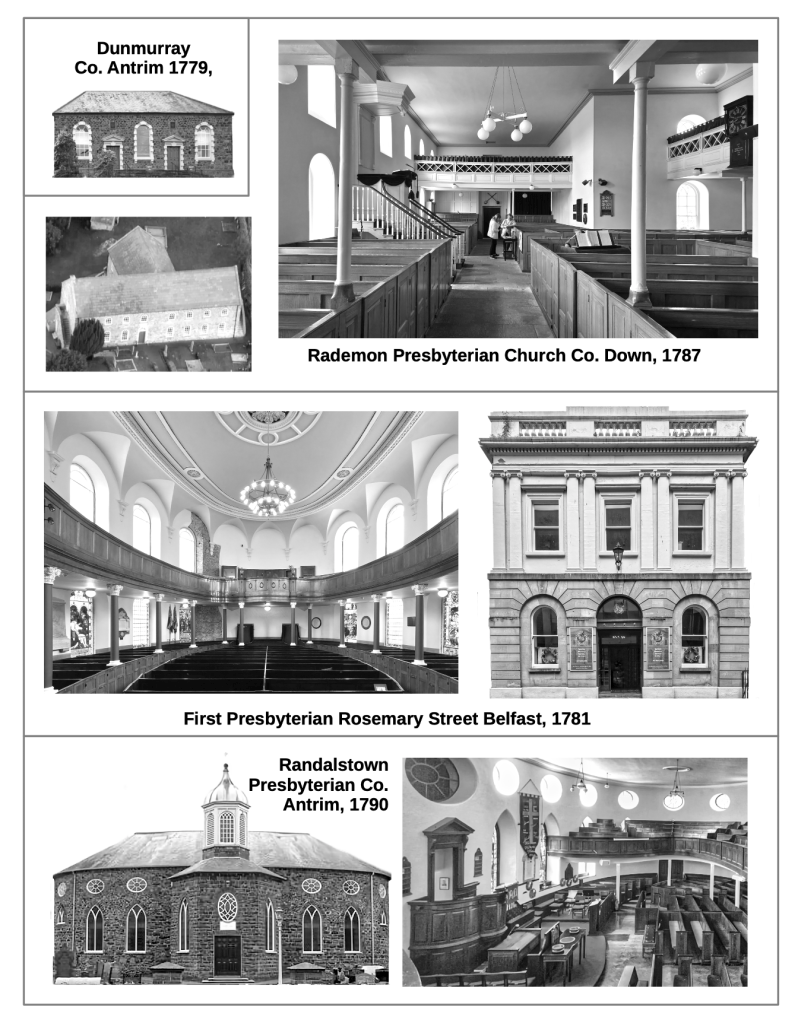

18th Century Presbyterian Churches

Like Catholics, Presbyterians in 17th- and early 18th-century Ireland faced heavy discrimination, limiting their ability to build churches. Only in the later 18th century, as restrictions eased, did they begin constructing more significant places of worship.

One of the earliest examples is the chapel at Dunmurry, a plain rectangular structure whose windows are framed with Gibbs-style surrounds. At Rademon, the congregation adopted a T-shaped floor plan, a form with precedents in Scotland and Wales. The pulpit is positioned directly beside the main door, where latecomers were sure to attract attention.

Presbyterians also experimented with oval and octagonal plans. At Randalstown, later additions of an octagonal porch and oval windows (1829) enhanced the eccentric design, making it one of the most unique churches in Ireland.

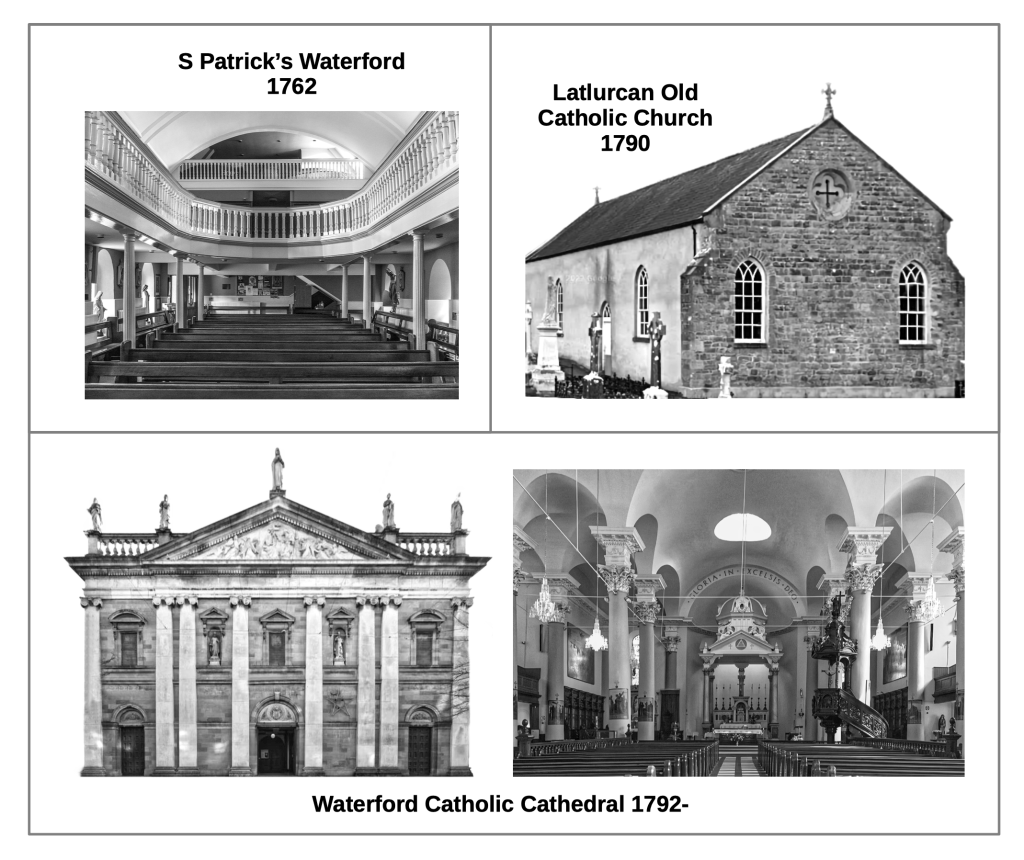

18th Century Catholic Churches

After more than two centuries of suppression, Catholic church building in Ireland began to cautiously re-emerge in the mid 1700s. The earliest surviving example is St. Patrick’s, Waterford (1764), discreetly tucked away on a side street at a time when Catholic worship was still restricted. The church is modest in scale, with no central aisle and a gallery squeezed into the small space to maximize seating. In the countryside, the Latlurcan Old Catholic Church offers another rare survival from the period, a simple rural chapel now repurposed as a mortuary church.

A major turning point came with the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, which eased restrictions and allowed more public expressions of Catholic worship. Within a year, the Waterford Catholic Cathedral was built. Its architecture is conservative, adopting the established Gibbs style. While neoclassicism and Gothic revival were already reshaping church design elsewhere, the cathedral’s conservative style reflected the Catholic Church’s desire to re-enter the cultural mainstream without breaking boundaries.

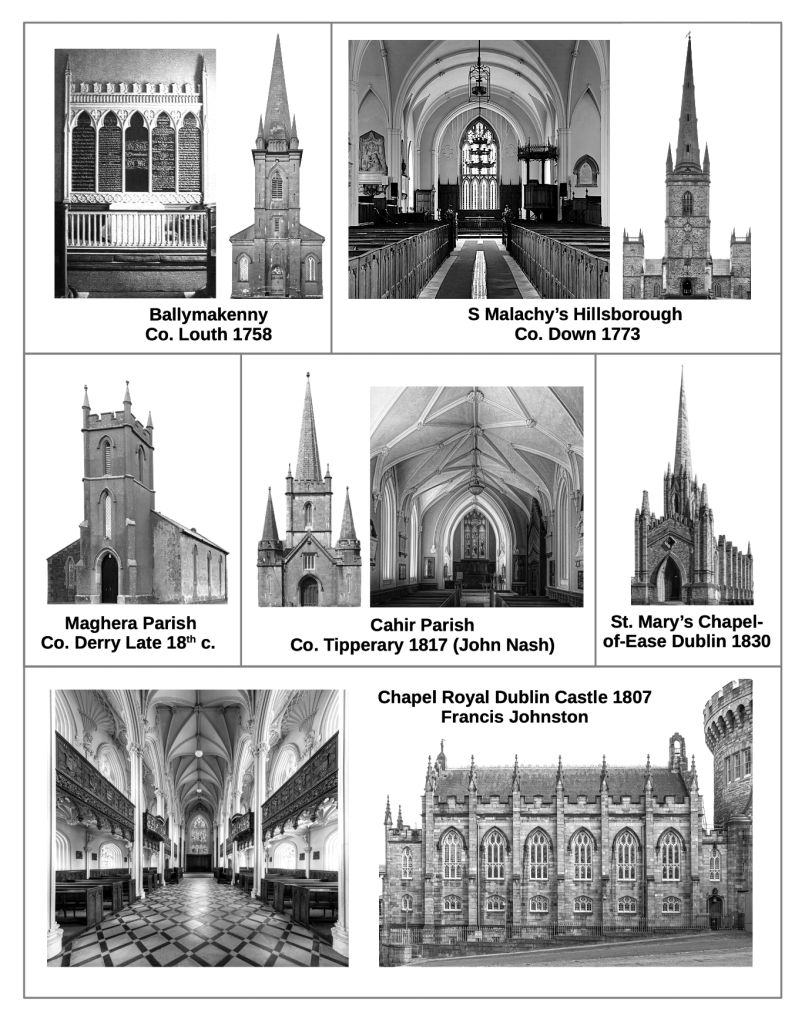

Early Church of Ireland Gothick

In the late 18th century, the Church of Ireland began adopting the “Gothick” style, a picturesque and fanciful mode popularized in the writings of Batty Langley. Unlike the historically informed Gothic Revival that would follow in the 19th century, Gothick was not an attempt to replicate medieval models but rather to evoke their atmosphere through playful ornament and romantic effect.

One of the earliest Gothick churches in Ireland is the chapel at Ballymakenny (now a Baptist church). A more ambitious example is St. Malachy’s Hillsborough, often considered the first Irish masterpiece of the style, celebrated for its elaborate carved woodwork. Other important works include the fairy-tale-like Cahir Parish Church and the imposing St. Mary’s Chapel-of-Ease in Dublin, both early 19th-century buildings that embraced Gothick’s free and evocative character.

At the same time, simpler churches were built under the patronage of the Board of First Fruits, a government grant scheme supporting Anglican construction. These modest chapels, often in plain classical or Gothic forms, became known as “First Fruits Gothic.” The Maghera Parish Chapel is a representative example.

The move from picturesque Gothick toward a more rigorous Gothic Revival came with Francis Johnston’s Chapel Royal in Dublin (1807). Here, Johnston drew directly on authentic medieval sources, incorporating Tudor-style fan vaulting and Decorated Gothic window tracery. With this, Irish architecture entered a new phase: one that would soon transform the ecclesiastical landscape of the 19th century.

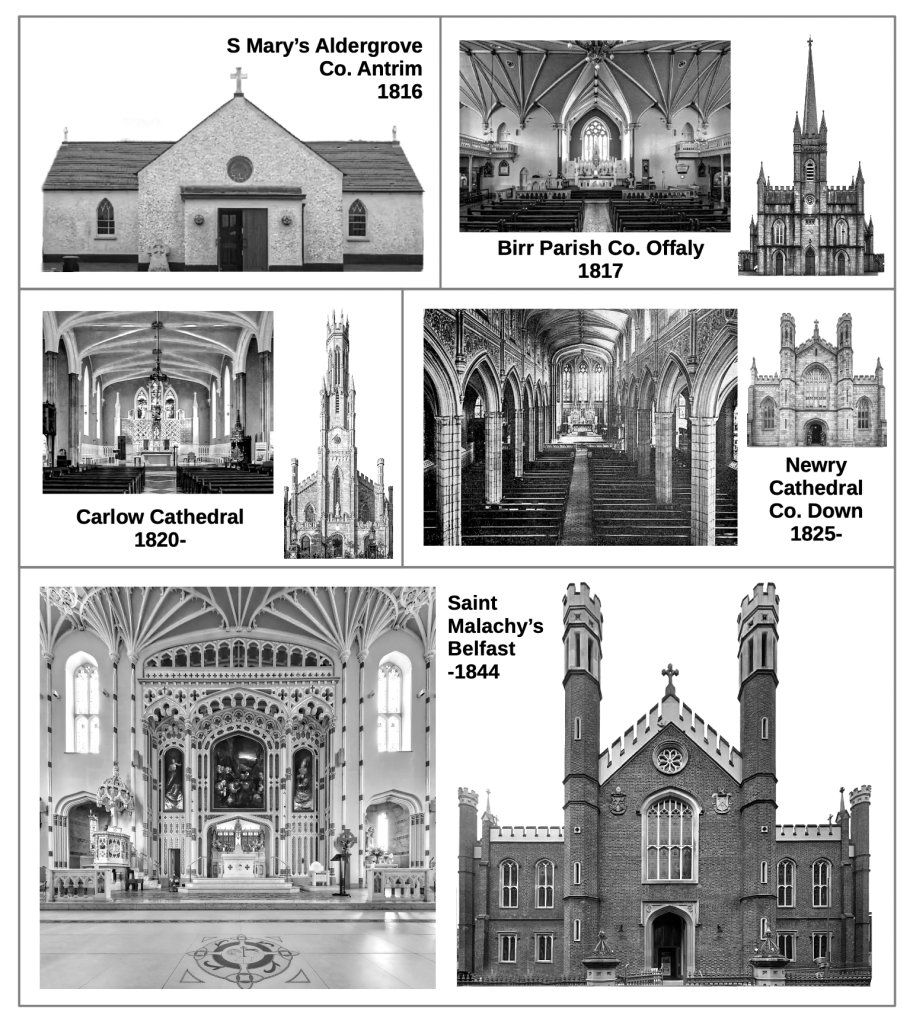

Early 19th Century Catholic Gothick

Irish Catholics were initially slow to embrace the Gothic Revival, partly due to lingering political restrictions and a preference for more discreet architectural forms. The modest Gothick Chapel of 1816 is a rare survivor from this early phase.

By the 1820s and 1830s, Catholic patrons began to commission increasingly ambitious Gothic Revival buildings. The parish church at Birr introduced a romantic, castellated Gothick style. Soon after, the Cathedral of the Assumption in Carlow set a new standard for Catholic architecture in Ireland with its soaring octagonal tower, a striking landmark visible for miles.

Other Catholic cathedrals drew directly on English royal models. Both Newry Cathedral and St. Malachy’s Belfast were designed with facades inspired by St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. Inside St. Malachy’s, Ireland’s most lavish pendent-vaulted ceiling was constructed, modeled on the celebrated fan vaulting at Henry VII’s Westminster Chapel (1503).

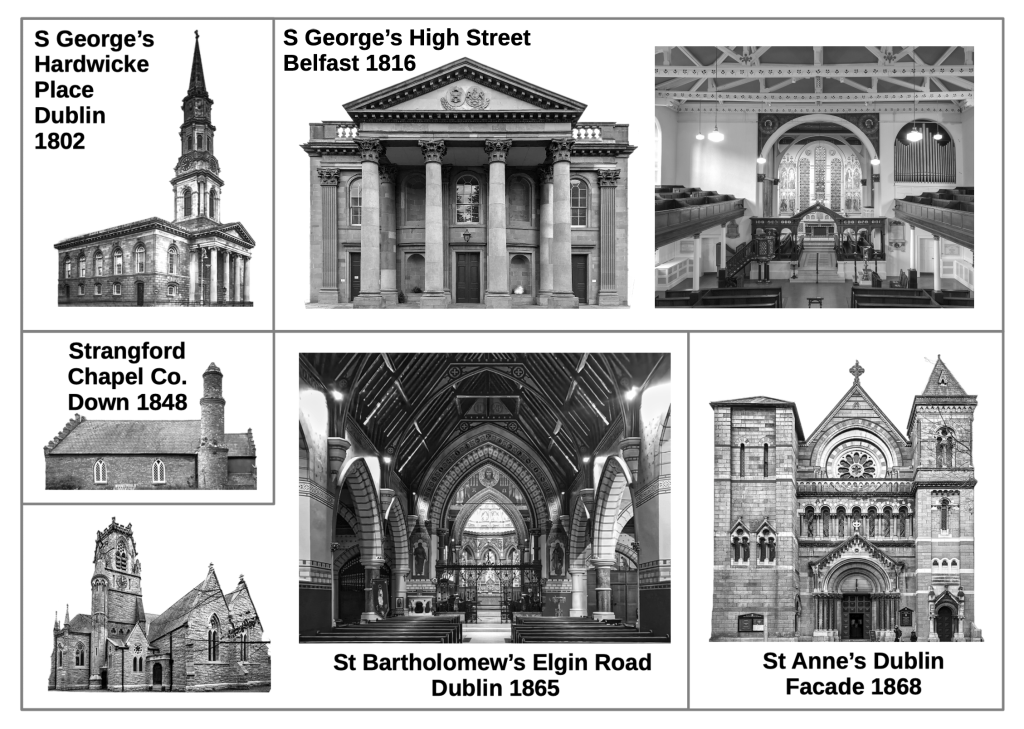

19th Century Church of Ireland Architecture

During the course of 19th century, the Church of Ireland entered a slow decline while the Catholic Church expanded rapidly. Nevertheless, the Church of Ireland continued to build churches in a wide variety of styles.

Francis Johnston, architect of the Gothic Chapel Royal, also designed St. George’s Hardwicke Place, a magnificent example of the Gibbs style, built long after it had gone out of fashion elsewhere. St. George’s High Street embraced a stately neoclassicism with fluted pilasters and a broad arched chancel.

The Strangford Chapel is notable for its round tower, inspired by Ireland’s 9th-century monastic precedents. Yet a true Celtic Revival would not emerge until the early 20th century, when native forms were more systematically revived.

By the mid-19th century, the influence of Victorian High Gothic reached Ireland through the writings of John Ruskin, who championed a lively, polychromatic Venetian Gothic style. St. Bartholomew’s in Dublin and the façade of St. Anne’s are both products of this movement. St. Anne’s combines Gothic elements such as a rose window with Romanesque Revival round-arched arcades.

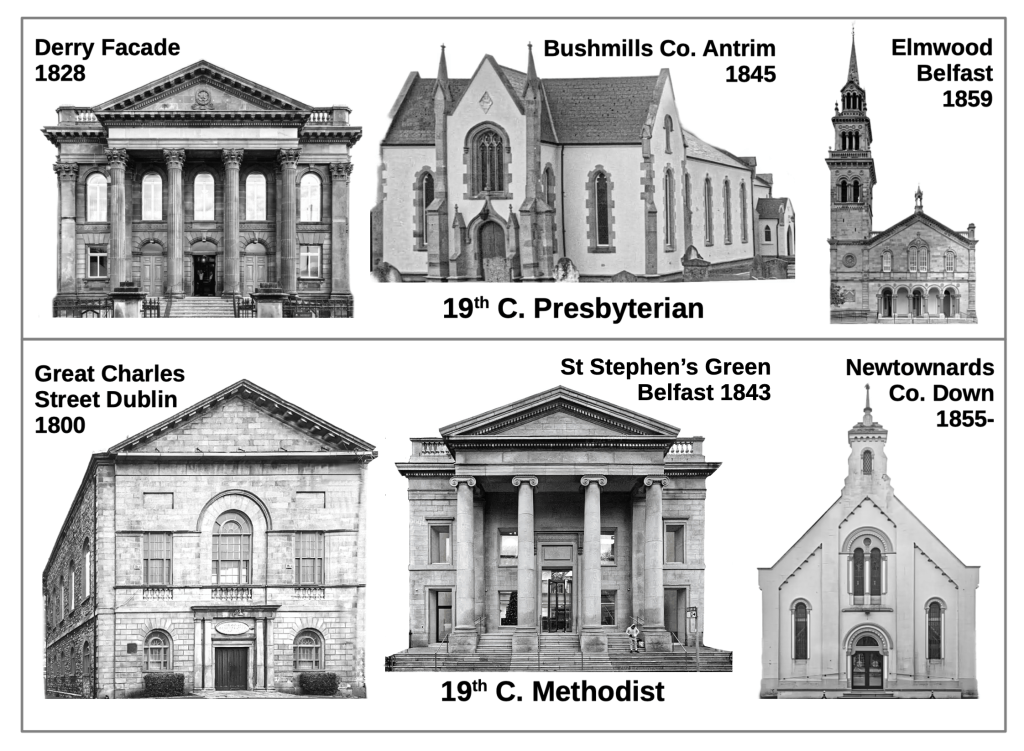

Presbyterian and Methodist 19th Century Churches

Presbyterian and Methodist congregations built prolifically during the 19th century, experimenting with a wide range of styles. Many Presbyterian Churches were built in the Greek Revival style, as seen in the dignified façade at Derry, while others explored Gothic and eclectic forms. At Bushmills, the familiar Presbyterian T-shaped floor plan was given Gothic cladding. The church at Elmwood showcases an Italianate Romanesque Revival style.

Early Methodist chapels leaned toward simplicity. The Great Charles Street Methodist church, one of the earliest surviving Wesleyan meetinghouses, is a spare neoclassical structure, almost unrecognizable as a church in its austerity. By mid-century, Methodists began to adopt more fashionable idioms: the St. Stephen’s Green church reflects the popularity of Greek Revival, while the chapel at Newtownards is representative of the many modest Methodist chapels designed in a vernacular Gothic style.

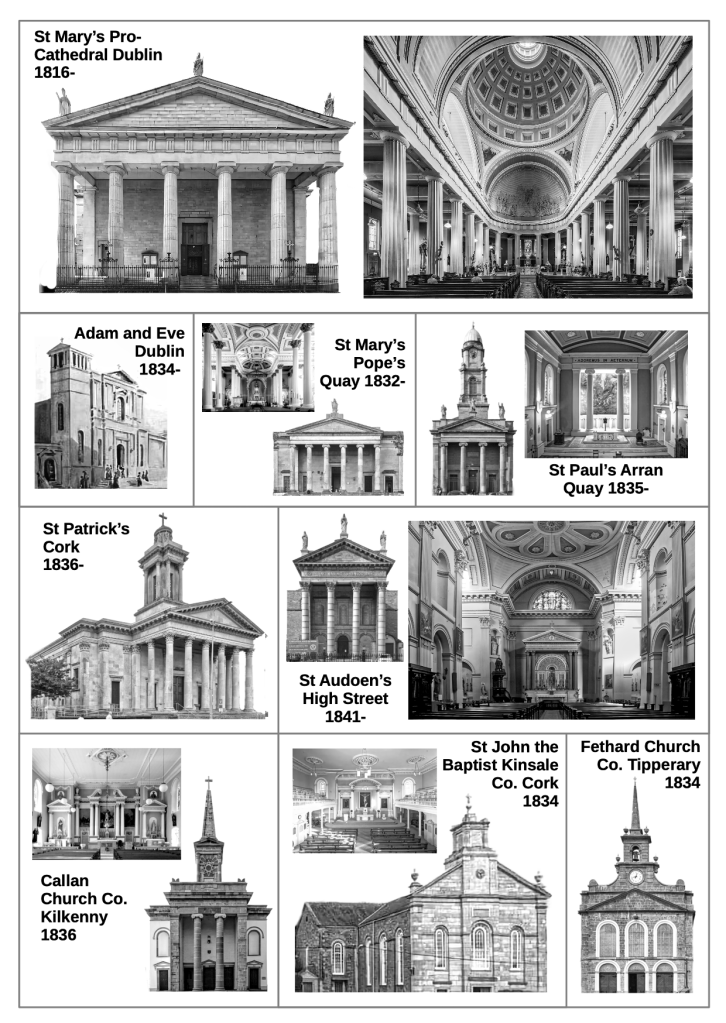

Catholic Greek Revival 19th Century Churches

The second great Catholic cathedral built in Ireland after Waterford was St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral Dublin (1816–). Designed in Greek Revival Doric, it symbolized Catholic aspirations in the years leading up to Emancipation in 1829. Other notable Greek Revival details appear in the temple-inspired towers of Adam and Eve’s Dublin and St. Patrick’s Cork. The Callan Church and the chancel of St. Paul’s, Arran Quay employ ‘distyle in antis’ fronts—two columns placed between projecting walls—directly derived from ancient temple architecture.

At St. Mary’s, Pope’s Quay, the relatively flat ceiling supported by tall columns suggests the architect’s adherence to the “primitive hut” theory, which prized trabeated construction over arches. St. Audoen’s, High Street drew inspiration from Renaissance precedents like Alberti’s Sant’Andrea Mantua, which was itself based on a series of Roman triumphal arches.

Not all classical experiments were successful. The chancel of Callan Church is overloaded with Baroque ornament, while the towers at St. John the Baptist, Kinsale and Fethard appear undersized and unsatisfying within their façades.

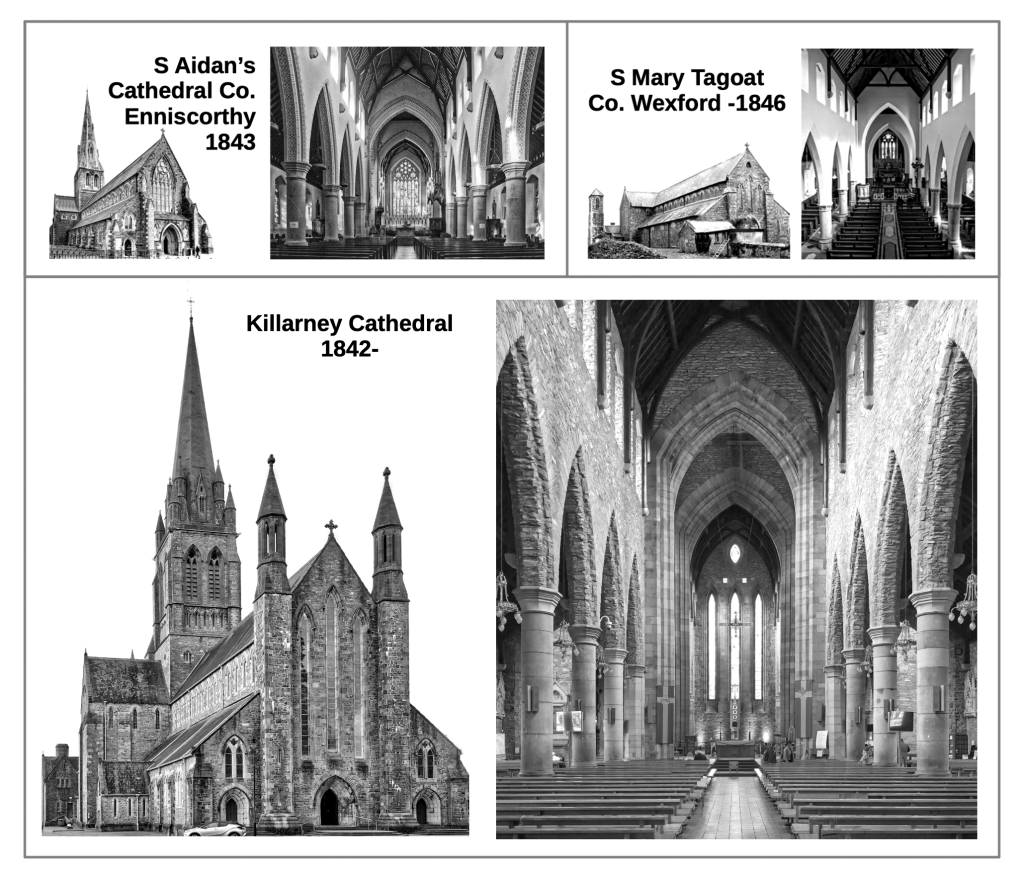

Augustus Pugin Gothic Revival

The Gothic Revival took a new turn in the mid-19th century through the influence of Augustus Pugin, who championed a historically faithful return to medieval design. Pugin regarded Killarney Cathedral as his greatest masterpiece. While its overall form follows the 14th century Decorated Gothic parish model, it also departs in significant ways. The use of heavily rusticated stone on the walls gives the interior a rugged, almost primitive character, unlike the smoother finishes of its English counterparts. Pugin also pushed Gothic proportions to new extremes, with slender, elongated forms that heighten the drama of vertical ascent. Instead of the usual circular or rose window, he topped his lancets with a mandorla-shaped opening, further accentuating the sense of verticality.

The cathedral’s west doors are particularly distinctive. Their archivolts strip away columns and capitals entirely, leaving a clean, minimalist outline that anticipates the abstract geometry of Art Deco.

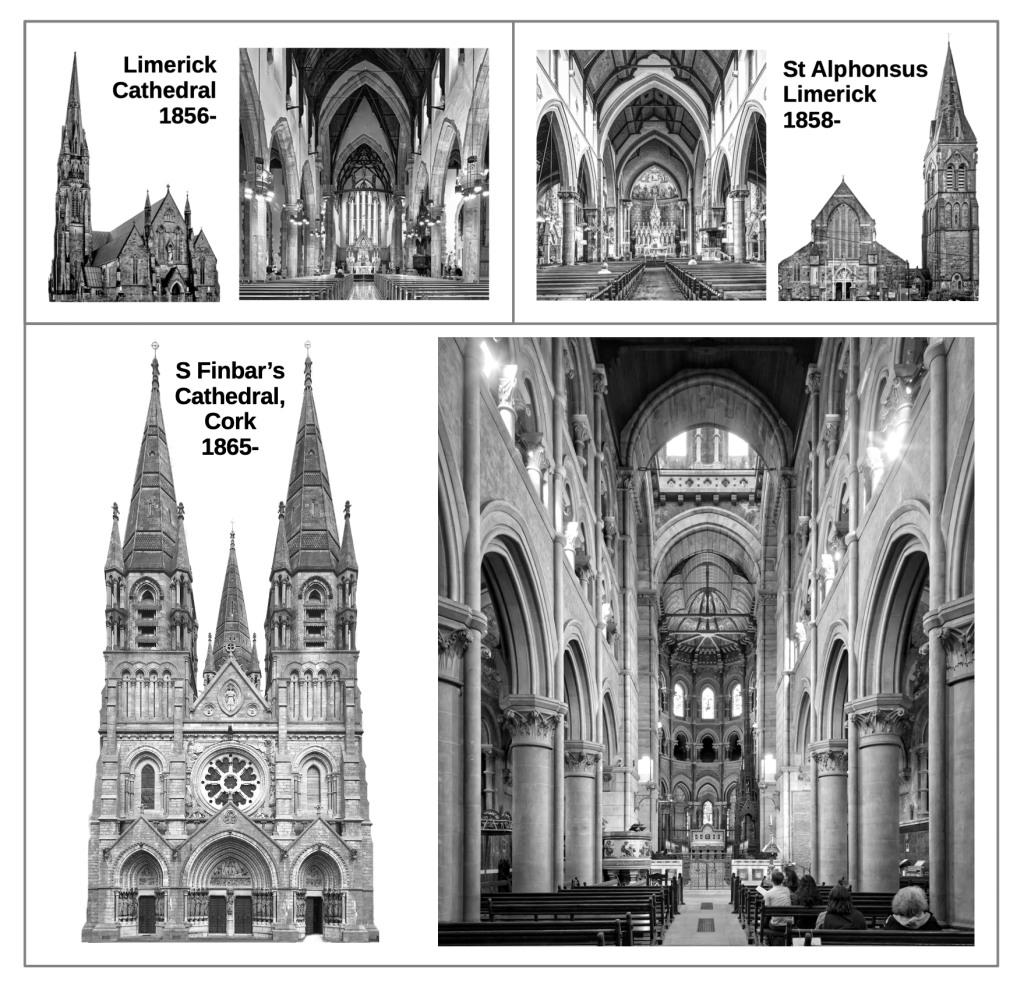

Phillip Charles Hardwick and William Burges

Philip Charles Hardwick, an English architect best known for his Italianate buildings in London, also designed a number of fine Gothic churches in Ireland inspired by Pugin’s ideals. Notable contributions include St. John’s Cathedral and St. Alphonsus in Limerick.

The greatest 19th century Church of Ireland church is undoubtably William Burges’ St. Finbar’s Cathedral in Cork. Burges was one of the greatest 19th century architects and a founder of the Arts and Crafts movement. An atheist, he nevertheless built St. Finbar’s according to an iconographic scheme rich with religious symbolism derived from his extensive knowledge of the medieval church. Architecturally, Burges drew from a mixture of English and French models. The English influences are most apparent in the interior elevations, while the exterior is derived from High Gothic French models.

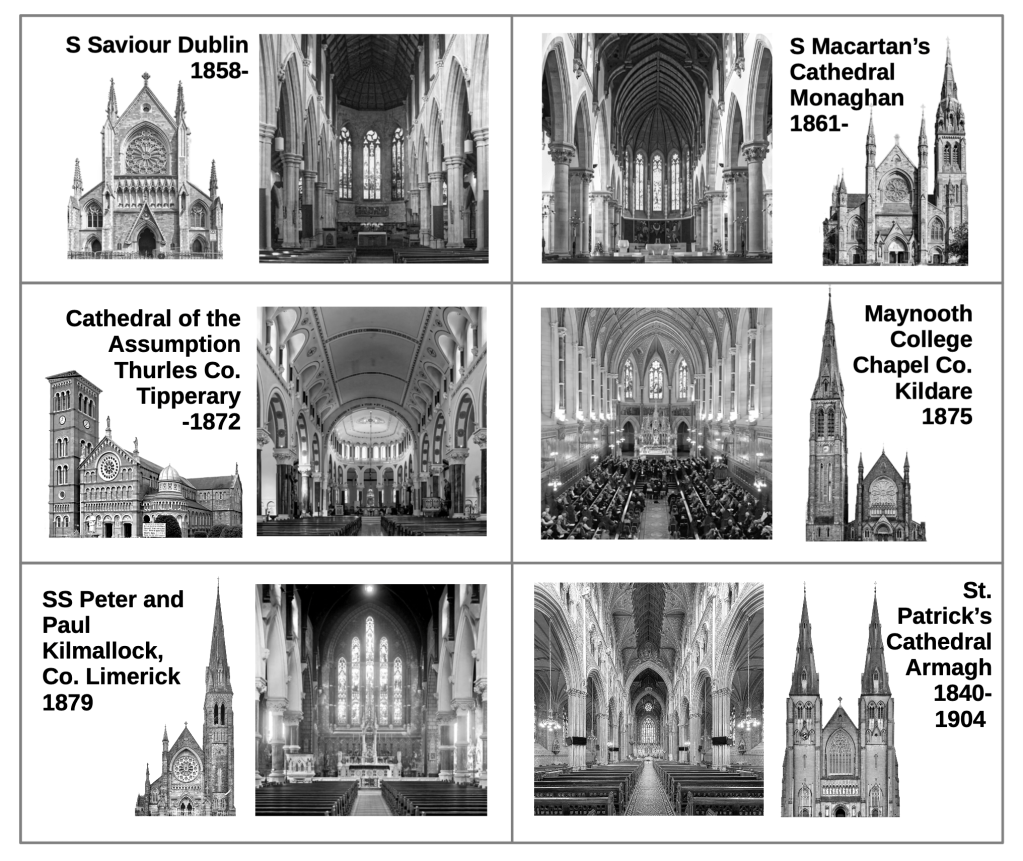

J.J. McCarthy

J. J. McCarthy was Ireland’s greatest native-born Gothic Revival architect, responsible for designing more than 80 churches and cathedrals. He drew from a range of medieval and Renaissance influences. St. Saviour Dublin takes inspiration from the great south transept facade at Notre Dame Paris. The Cathedral of the Assumption Thurles draws on Italian Romanesque (figure 6 Evolution of the Church Facade). SS Peter and Paul Kilmallock, built in 1879 revisits the beautiful rose windows McCarthy perfected at S. Saviour and S. Macartan’s. It also includes a lovely set of rounded lancets in the chancel, likely inspired by the clustered lancets of ruined Irish abbeys (Part I, figure 11).

McCarthy’s crowning achievement is St. Patrick’s Cathedral Armagh. However its current splendor is due in large part to the extraordinary murals and painted decoration added in the early 20th century, which cover nearly every surface of the interior.

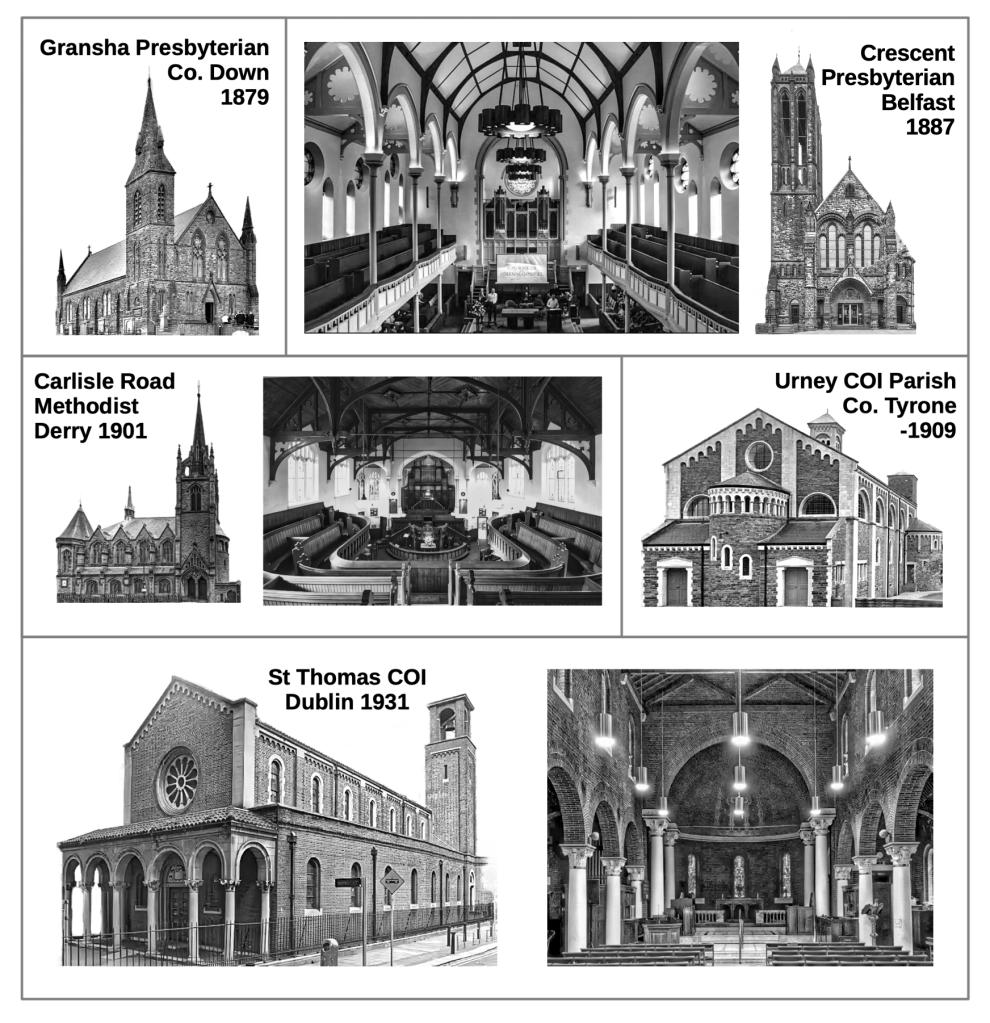

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Presbyterian, Methodist, and COI Churches

Late 19th century Presbyterian and Methodist congregations avoided the academic High Gothic styles championed by Pugin and McCarthy, which were ill-suited to Protestant worship. They stuck to eclectic Gothic and Romanesque Revival styles that could be adapted to accommodate their wide galleried chapels fronted by organs and prominent pulpits. One of the finest of these is Carlisle Road Methodist, which features an attractive hammer-beamed ceiling and beautiful gallery. Its exterior is dominated by a lofty lantern tower and a row of Perpendicular Gothic style clerestory windows, each one its own dedicated gable, lending it a slightly domestic appearance.

The Church of Ireland built two notable early 20th century churches: Urney Parish adopted the Italian Romanesque style including an apse with a dwarf gallery and a prominent set of polychromatic Lombard bands. St. Thomas Dublin takes inspiration from early 5th and 6th century churches in Rome and Ravenna (see Evolution of the Church Floor Plan Part 1 figures 1 & 2).

An Túr Gloine and the Hiberno-Romanesque Revival

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the Celtic Revival, a cultural movement closely tied to Irish nationalism. One of its most important expressions was the Dublin stained-glass cooperative An Túr Gloine (“The Tower of Glass”), founded in 1903. Its artists drew on early insular manuscript and sculptural traditions, creating a distinctly Irish iconography of saints and biblical figures enacting legendary events in Celtic Christianity.

Although not formally a member, Harry Clarke—Ireland’s most celebrated stained-glass artist—collaborated with An Túr Gloine on the great Celtic Revival project of the Honan Chapel, Cork. The chapel exemplifies the Hiberno-Romanesque Revival: its façade recalls the 12th-century church of St. Cronan, Roscrea (see Part I, figure 6), while its interior echoes the arcading of Cormac’s Chapel (see Part I, figure 5).

The Hiberno-Romanesque style was echoed in other early 20th-century Catholic churches. St. Patrick’s Newport features the iconic gabled arch, while St. Patrick’s Donegal adopts a steeply pitched stone roof and round tower, evoking Ireland’s early medieval monastic heritage. Though more conventional in plan, Loughrea Cathedral contains the largest collection of An Túr Gloine stained glass in Ireland, with contributions from Alfred Ernest Child, Michael Healy, Hubert McGoldrick, Evie Hone, Catherine O’Brien, and Sarah Purser.

The Last Revival Churches

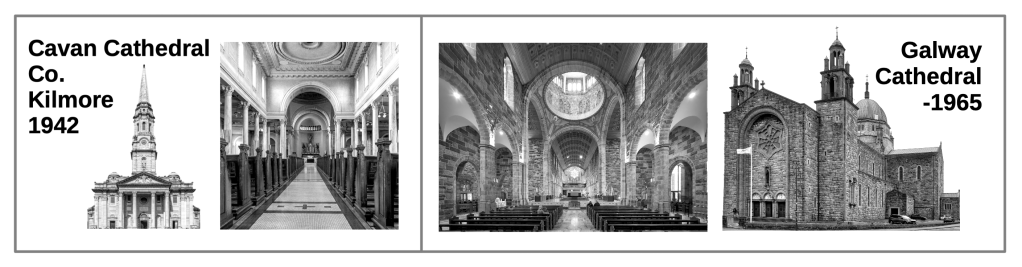

Before modernism definitively reshaped Irish church architecture in the mid-20th century, two final cathedrals were built in older revival idioms.

The first, Cavan Cathedral (1942), presents a sober Gibbs-style exterior that closely recalls St. George’s Hardwicke Place, Dublin (see figure 10). However its interior adopts a primitive Christian style: flat clerestory walls rise above a trabeated colonnade without arches, in direct imitation of the earliest Roman basilicas (see Evolution of the Church Floor Plan Part 1 figure 2).

Galway Cathedral (-1965) contains no such historical allusions. Built in an eclectic style with a vaguely medieval flavor, it features unique tracery patterns that don’t seem to have been derived from any previous style. However the two towered facade may derive from Spanish Colonial prototypes.

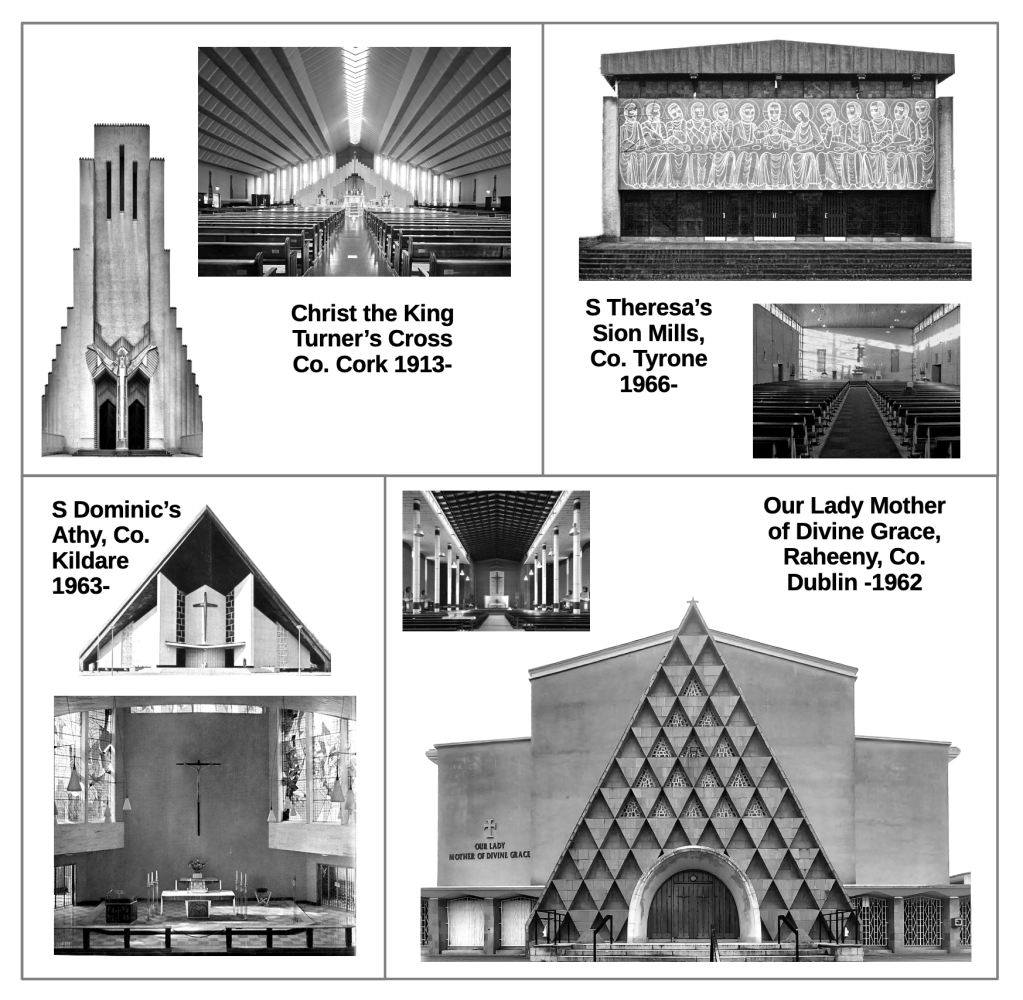

Modernism

The first significant modernist experiment in Ireland was Christ the King Cork (1913–), designed by American architect Barry Byrne. Executed in the then-fashionable Art Deco style, it was an imaginative departure from Irish norms. Yet Byrne’s proto-modernist vision proved too radical for its time, and the building remained an outlier in a country still largely committed to revivalist idioms.

It was not until the 1960s that modernist churches began to appear more widely. St. Theresa’s, Dublin, designed by Patrick Haughey, combines a spare International Style interior with a semi-Brutalist exterior. Its abstract geometry is softened by a frontispiece carved by Oisín Kelly, whose primitive iconography anchors the church in a recognizably religious idiom.

Other churches reflected international trends. St. Dominic’s, Athy, by John Thompson & Associates, resembles the space-age suburban churches being built across the United States at the same time. It was the first church in Ireland to implement the Vatican II reform of placing the altar forward, so the priest could celebrate facing the congregation.

Some architects sought to blend modernist form with historical reference. Our Lady Mother of Divine Grace, Raheny reinterprets the Hiberno-Romanesque gabled arch (see Part I, figure 6). The repeated triangular motifs echo the gable of Clonfert Cathedral (12th century), demonstrating how modernist abstraction could still engage with Ireland’s medieval heritage.

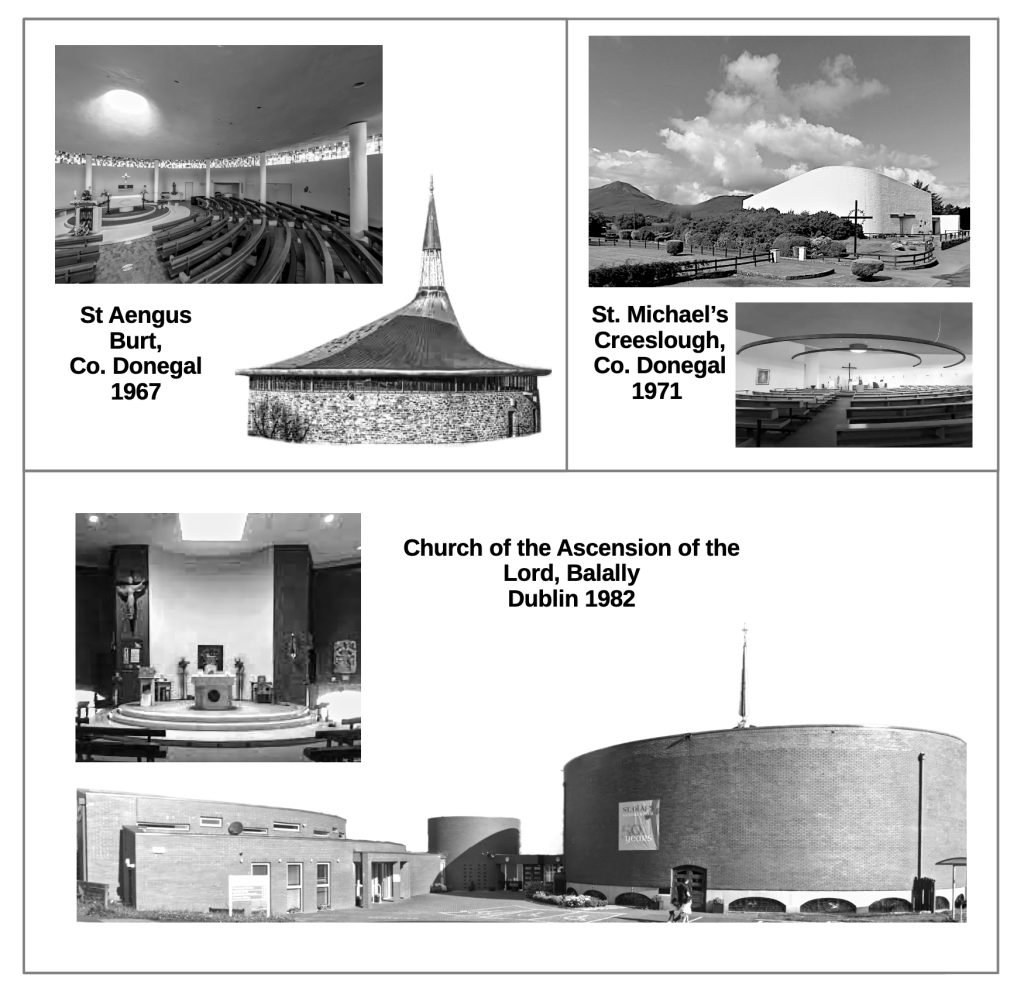

Liam McCormick

Liam McCormick designed some of the finest modern churches in Ireland. Embracing the liturgical reforms of Vatican II, he pioneered a new approach to ecclesiastical design that emphasized communal worship around a centralized altar. His churches broke with rigid geometric modernism, favoring instead organic forms that harmonized with their natural surroundings.

St. Aengus Burt is one of McCormick’s masterpieces: a circular church where light pours directly onto the altar from a lantern steeple, dramatizing the central focus of worship. St. Michael’s Creeslough was designed so that its silhouette echoes the surrounding hills, rooting the church in its Donegal landscape. Meanwhile, the Church of the Ascension of the Lord Drumboe, is inspired by cylindrical forms of Eero Saarinen’s iconic MIT Chapel (1955).

Into the 21st Century

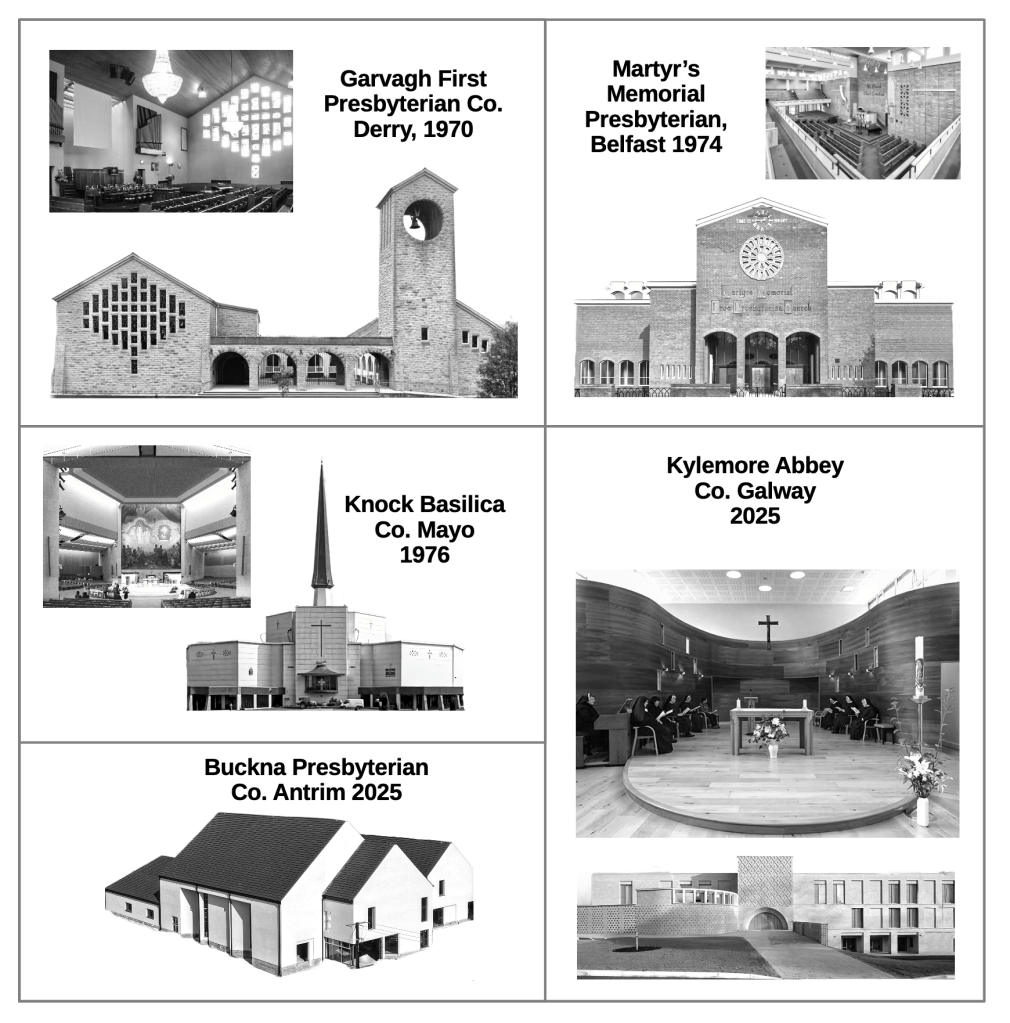

In contrast to Catholic modernists such as Liam McCormick, who embraced abstraction and organic form, Presbyterian congregations favored modern designs that retained recognizably ecclesiastical motifs. The Garvagh First Presbyterian church resembles a monastery complex, complete with an arcaded walk and bell tower. Ian Paisley’s Martyr’s Memorial church in Belfast is likewise traditional in its arrangement despite its spare modernism. Its pulpit, placed directly beneath the rose window of the façade, follows a long Presbyterian convention: placing the entrance close to the pulpit, as seen earlier at Rademon Presbyterian (figure 6).

Catholics, meanwhile, erected the largest church by capacity in Ireland at the Basilica at Knock Shrine in 1976. It was built to commemorate a Marian apparition to local villagers in 1879. Like McCormick’s designs, the basilica is centralized, but its stepped, pyramid-like massing and tall central steeple recall the mid-century modern Gothic being built in the United States by architects like Harold Wagoner (see Evolution of the Church Facade fig. 28).

Church construction in Ireland declined sharply in the late 20th century, mirroring trends in the United States and elsewhere. However, two significant church projects have recently been completed. The new monastery at Kylemore Abbey, winner of the 2025 RIAI Public Choice Award, is a minimalist campus built of pale brick, fronted by a short tower with a wide arch that subtly echoes medieval motifs (as at Our Lady Mother of Divine Grace, see figure 19). The chapel is articulated by a simple curved wall housed within a larger rectangular shed.

The new Buckna Presbyterian Church, dedicated in 2025, is unrecognizable as a church. Built in a minimalist farmhouse style common to domestic architecture, it reflects a trend familiar in the United States: the “non-church” church. Here, emphasis is transferred away from the architecture and directed toward lighting, sound, and multimedia performance.

Unlike the United States, where a revival called “new classicism” has begun, no such movement has yet taken root in Ireland. When and if it does, however, Ireland will have a rich tradition of architectural heritage—from early Christian stone huts and Hiberno-Romanesque arches to Gothic cathedrals and Celtic Revival chapels—to draw upon for inspiration.

Resources Consulted

De Breffny, Brian, and George Mott. The Churches and Abbeys of Ireland. Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1976.

Harbison, Peter, Woman Potterton, and Jeanne Sheehy. Irish Art and Architecture from Prehistory to the Present. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

Hourihane, Colum. Gothic Art in Ireland, 1169-1550. Yale University Press, 2003.

O’Keeffe, Tadhg. Medieval Irish Buildings 1100-1600. Four Courts Press, 2015.

O’Reilly, Séan D. Irish Churches and Monasteries. The Collins Press, 1997

Seaborne, Malcom. Celtic Crosses of Britain and Ireland. Shire Publications LTD, 1994

Walker, Simon. Historic Ulster Churches. Queens University Belfast, 200.

Photo Credits

Most of the photos in these figures are taken from wikimedia commons and have been released under Creative Commons BY 4.0. When I could not find open access images, I lifted them from google map contributors, personal blogs, or travel websites. Please contact me if you have any concerns about my use of your image.

Figure 1: Middle Church exterior (lisburn.com), Middle Church interior (Kenneth Allen), St. Michan’s (JSTOR).

Figure 2: St. Mary’s exterior (author), interior (author), St. Werburgh’s exterior (author), interior (Internet Archive Book Images), St. Anne (Dobrin Gueorguiev), Ballymore (Rossographer).

Figure 3: St. Peter’s exterior (author), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Cashel exterior (author), interior (Cashel Union), Waterford interior (David Stanley), exterior (Google Maps Street View). St. Martin (Yale Center for British Art)

Figure 4: Coolbanagher interior photo (author), interior drawing (theirishaesthete), exterior (author), Trinity (author), interior (tcd.ie), St. Catherine interior (saintcatherines.ie), exterior (Google Maps Street View), Wilson’s (WilsonsWestmeath), York Assembly (digit.en.s), S. Iberius interior (Andreas F. Borchert), model (Michael Breathnach).

Figure 5: Rotunda (NBHS), Donabate interior (Brian Scott), Ballycastle exterior (Andreas F. Borchert), interior (Andreas F. Borchert).

Figure 6: Dunmurry (Brian Shaw), Rademon exterior (rademonchurch.wordpress.com), Rademon interior (author), Belfast interior (author), exterior (author), Randalstown exterior (Kenneth Allen), interior (Ryan Nicol)

Figure 7: St. Patrick (William Murphy), Latlurcan (Google Maps Street View), Waterford Cathedral interior (Andreas F. Borchert), exterior (Google Maps Street View).

Figure 8: Ballymakenny exterior (author), interior (unknown google image), Hillsborough interior (author), exterior (author), Maghera (Michael Spense), Cahir (archiseek.com), Chapel Royal interior (Diliff), exterior (Marek Sliwecki).

Figure 9: Aldergrove (lisburn.com), Birr (author), Carlow exterior (author), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Newry interior (Dshort5551), Newry exterior (Google Maps Street View), Malachy interior (author), Malachi exterior (Google Maps Street View).

Figure 10: St. George Hardwick (Google Maps Street View), St. George Belfast (Plamen Stoyanov), St. George interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Strangford (Gavin Sloan), St. Bartholomew’s exterior (myhome.ie), interior (hhcarchitecture.ie), St. Ann (Paul Hermans)

Figure 11: Derry (Andreas F. Borchert), Bushmills (Google Maps Street View), Elmwood (Suzanne Mischyshyn), Great Charles Street (hMTV), St. Stephens (Google Maps Street View), Regent Street (Google Maps Street View)

Figure 12: St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral exterior (author), interior (author), Adam & Eve (William G. Spenser), St. Mary’s Pope’s Quay exterior (author), interior (Niels Freckmann), St. Paul’s exterior (author), interior (permia), St. Patrick Cork (author), St. Audoen exterior (author), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Callan interior (The Speckled Bird), exterior (The Speckled Bird), Kinsale (churchservices.tv), Fethard (Patrick Mc Donnell)

Figure 13: St. Aiden’s exterior (Andreas F. Borchert), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Tagoat interior (buildingsofireland.ie), exterior (buildingsofireland.ie) Killarney exterior (author), interior (author)

Figure 14: Limerick exterior (JohnArmagh), interior (Mike Abrams), Redemptorist exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (Fergus Hurley), St. Fin Barre exterior (author), interior (author)

Figure 15: St. Saviour exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (Stefan Odd Gruszcynski), St. Macartan’s exterior (Andreas F. Borchert), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Thurles exterior (Andreas F. Borchert), interior (Andreas F. Borchert), Maynooth interior (Ianmccurdy), exterior (Bart Busschots), Kilmallock exterior (author), interior (Robert French), Armagh exterior (author), interior (author)

Figure 16: Gransha (David Monroe), Crescent Church interior (Illuxtron), exterior (author), Carlisle Road exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (National Churches Trust), Urney (Google Maps Street View), St. Thomas exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior(Frank McDonald)

Figure 17: Loughrea exterior (Google Maps Street View), Loughrea window (author), Newport (buildingsofireland.ie), window (Patrick), St. Barrahane’s (fiona), Honan exterior (author) window (author), Donegal (Declan Surpless)

Figure 18: Cavan exterior (Olliebailie), interior (Oliver Gargan), Galway exterior (author), interior (author)

Figure 19: Christ the King exterior (author), interior (Finn), Sion Mills exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior Kenneth Allen), St. Dominic’s exterior (rte.ie), interior (athyphotos.gallery), Raheeny exterior (Philip Doyle), interior (Anna K.)

Figure 20: Creeslough exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (markstephensarchitects.com), St. Aengus interior (Peng Shi), exterior (Christ Newman), Church of the Ascension exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (Ireland’s Churches, Cathedrals and Abbeys)

Figure 21: Garvagh exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (dynamicsavs.com), Martyr’s exterior (Google Maps Street View), interior (Martyr’s Memorial Productions), Knock interior (FredSeiller), exterior (Google Maps Street View), Buckna (bucknapresbyterian.org), Kylemore exterior (kylemoreabbey.com), interior (kylemoreabbey.com)

Leave a comment