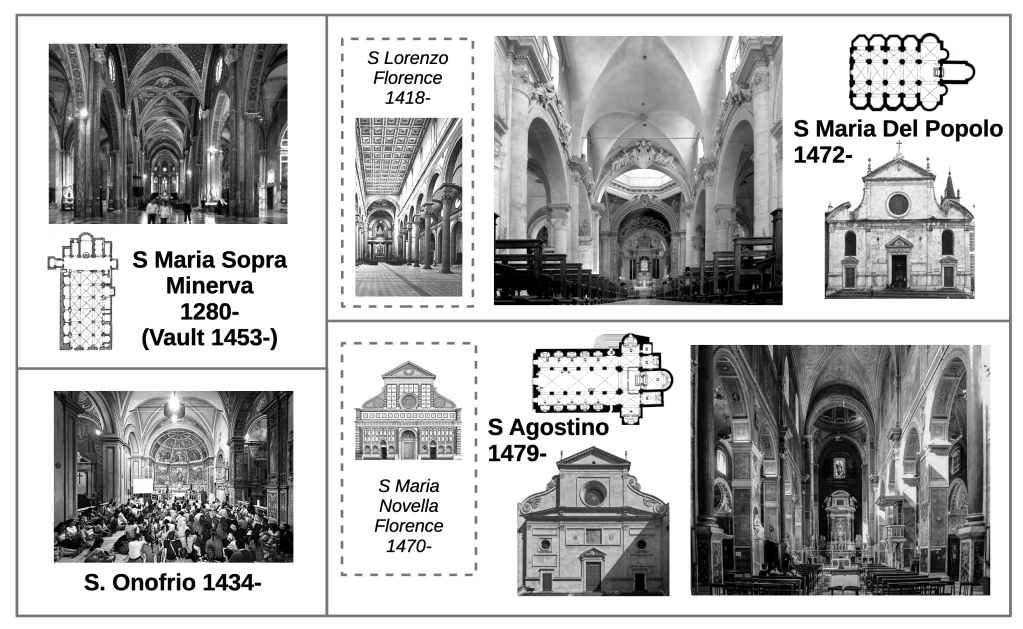

The evolution of Renaissance church architecture in Rome begins, paradoxically, with a Gothic structure: Santa Maria sopra Minerva, founded around 1280. When the papacy returned from its exile in Avignon, it undertook to complete the church’s unfinished vaulted ceiling in 1453. Constructing a ribbed vault required considerable technical expertise, and this revival of medieval building practice meant that groin-vaulted construction remained the Roman norm throughout the fifteenth century, even as architects in Florence and northern Italy were experimenting with flat-ceilings inspired by ancient Christian basilicas or domed spaces derived from imperial Roman precedents.

The earliest church in Rome built during the Renaissance, Sant’Onofrio al Gianicolo (1434-), still employed a medieval vaulted system but replaced side aisles with compartmentalized chapels—a popular late Gothic layout first introduced at the church of Santa Catalina in Barcelona (1243). Its proportions are unusually broad, and its interior is strongly unified, in contrast to the early Renaissance churches of Florence such as Brunelleschi’s San Lorenzo (1418-), whose modular bays consciously revive the early Christian basilican form and its compartmentalized character. Sant’Onofrio abandons Gothic detailing in favor of a restrained classical paneling scheme. The interior was later enriched with more elaborate decoration in 1588, yet the underlying structure preserves its transitional character between Gothic form and Renaissance classicism.

Santa Maria del Popolo (1472–) and Sant’Agostino (1479) both adopted vaulted schemes similar to the Gothic model of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, yet they present two very different approaches to classical design. Santa Maria del Popolo, like Sant’Onofrio, is broad, with heavy piers buttressed by massive half-columns. Sant’Agostino, by contrast, replaces columns with tall square piers, creating a more vertically oriented space. Its height required substantial exterior buttresses, which posed a challenge for the facade’s design; the oversized scrolls added in 1746 were intended to conceal the butteresses. Both facades adapt the Florentine basilican prototype seen in Alberti’s Santa Maria Novella (1456-), although the compositions of these Roman examples remain more tentative and experimental than Alberti’s masterpiece.

15th c. Renovations to St. Peter’s Basilica

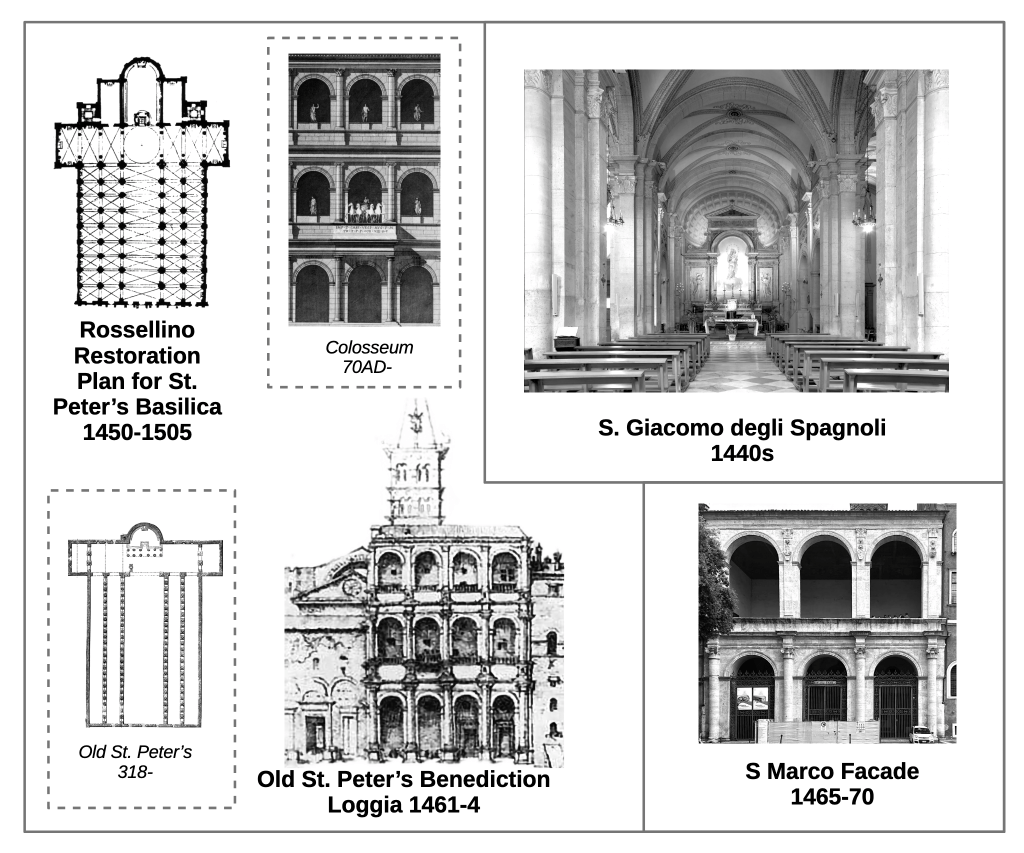

The most ambitious architectural undertaking in fifteenth-century Rome was Pope Nicholas V’s renovation of Old St. Peter’s Basilica, begun around 1450. Nicholas employed Bernardo Rossellino to oversee the remodel, intending not to replace the Constantinian structure but to replace its wooden roof with stone vaults. A surviving drawing of the proposed plan suggests that the piers of the doubled aisles were to be rebuilt, each bay covered by a groin vault. Although the project was abandoned when Pope Julius II later resolved to demolish the old basilica entirely, Rossellino’s scheme represents an early fusion of Gothic structure with Renaissance order. The contemporary remodel of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli (1440s) offers a glimpse of what Nicholas and Rossellino envisioned: Gothic piers and vaults refined with classical pilasters, impost blocks, and entablatures.

In the 1460s, a Benediction Loggia was erected at the edge of St. Peter’s forecourt, providing a platform from which the pope could address the faithful. Its design drew inspiration from the superimposed classical orders of the Colosseum (c. 75 AD) and the Theatre of Marcellus (13 BC). Although the loggia has been lost along with the old basilica, the surviving façade of San Marco (1465–) displays a similar arrangement of stacked arcades which seems to have been modeled on the Benediction Loggia. Here, Roman architecture begins to re-engage consciously with its own antiquity, marking a shift from classicizing Gothic to deliberate antique revivalism.

Late 15th c. Chapels

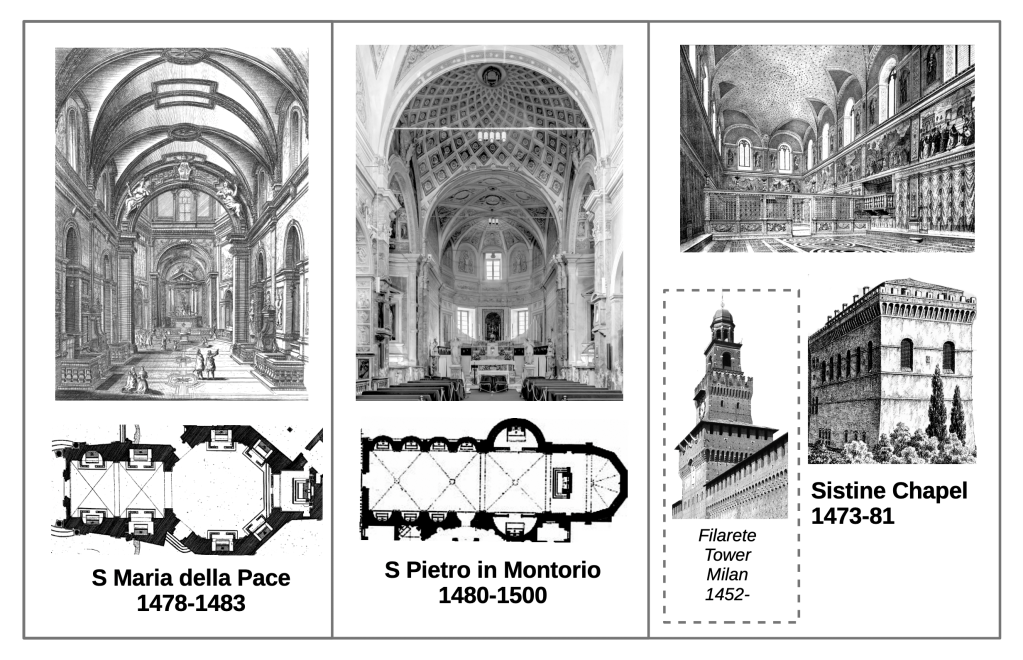

Three smaller, aisle-less churches constructed at the close of the fourteenth century illustrate the experimental nature of late medieval architecture in Rome. Santa Maria della Pace (1478-) was designed as a centrally planned, octagonal memorial church with a short nave attached, serving as a vestibule to the main domed structure. This design became a prototype for countless later variations across Italy. Though the church was extensively restored in the seventeenth century, the drawing in the illustration above shows an earlier iteration.

San Pietro in Montorio (1480-) follows the prototype of the numerous domed churches built during the Renaissance but stands out for the shallowness of its dome, which imparts a striking unity to the interior space.

The Sistine Chapel, by contrast, adopts a simple rectangular plan dictated by its function as a venue for papal and clerical assemblies rather than for public worship. Its brickwork closely resembles that of the contemporary Filarete Tower in Milan (1542–).

15th Century Palazzos

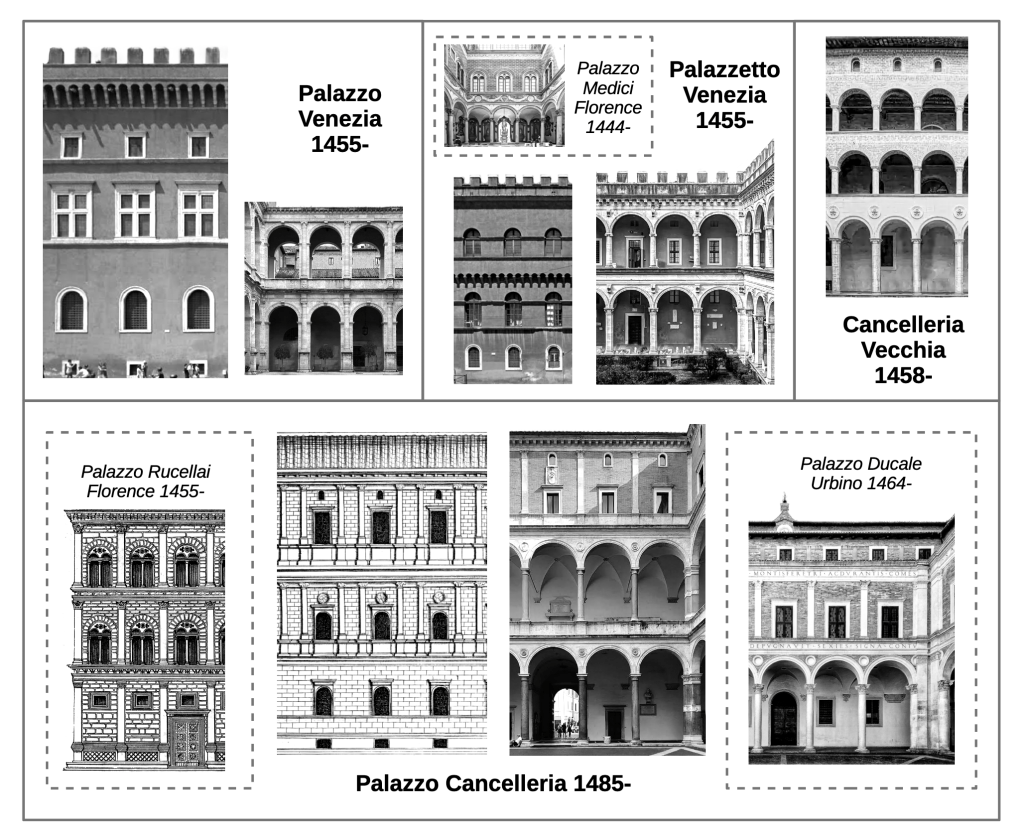

During the Renaissance, architects of palazzos began paying greater attention to the proportions of their facades, adding stringcourses, columns, and moldings to create balanced and harmonious compositions. One of the finest early examples is Leon Battista Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai in Florence (begun 1455). These palazzi included courtyards designed according to the same proportional logic. The most accomplished early example is the courtyard at the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino (1464-).

In Rome, the first successful attempt at the new style was Palazzo Venezia and its smaller attached Palazzetto. Their elevations retain medieval castelations and astylar windows. But the windows have been set within rationally organized stringcourses—an early effort to impose visual order on a traditional form. At the Palazzo Cancelleria (begun 1485), the architect introduced paired columns, the first such arrangement of its kind. These columns were spaced widely apart to evoke the ideal proportions of the so-called golden section, though later architects deemed the spacing excessive and placed their paired columns more closely together.

The courtyard of Palazzo Venezia employs arcades with attached columns as at St. Peter’s Benediction Loggia and the façade of San Marco (figure 2), both ultimately modeled on the elevation of the Colosseum. The courtyard of the adjoining Palazzetto features an arcade similar to that of the Palazzo Medici in Florence (1444–), but with reinforced corner columns that emphasize the shape of the overall courtyard—unlike the Medici Palace, which has undifferentiated, single columns at the corners.

The arcade of the Cancelleria Vecchia (1458-) showcases an early three-story arcade, while the courtyard of the Palazzo Cancelleria (begun 1485) displays a sophisticated interplay of arcades and windows inspired by the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. Yet by having two stories of arcades and using very slender columns, the Cancelleria produces a “top-heavy” effect, lacking the structural equilibrium that makes the Urbino courtyard the finest of the fifteenth century.

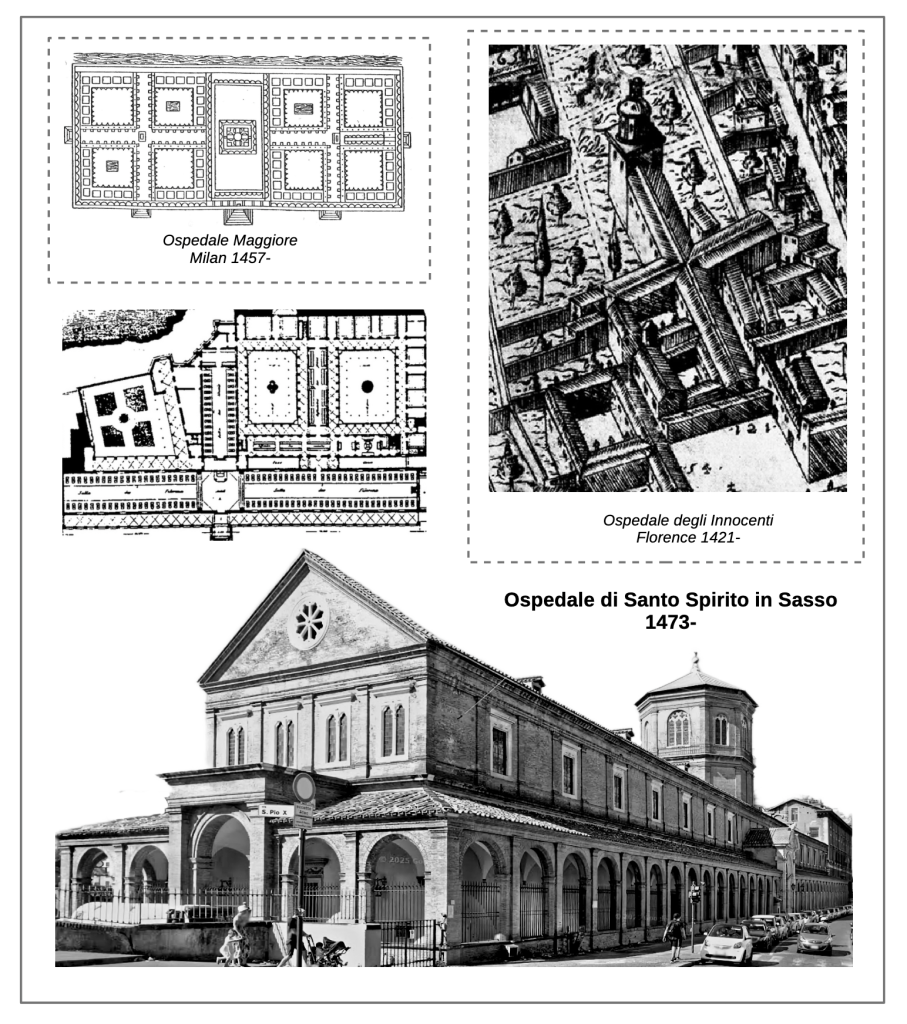

Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sasso

The last major architectural work of the fifteenth century in Rome was the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia (begun 1473). The complex consists of three wards arranged as long halls radiating around a central, octagonal tower. This plan represents a variation on the cross-shaped layout first introduced in Florence with Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti (begun 1421) and later expanded by Filarete in the double-cross plan of Milan’s Ospedale Maggiore (begun 1457). Filarete’s widely read architectural treatise further disseminated his ideas, strongly influencing subsequent hospital design, including this Roman hospital. Its octagonal tower is also Lombard motif, as seen at the Duomo di Pavia (1488), suggesting a further link between Milanese architectural practice and the hospital’s design in Rome.

Mass was celebrated in the central octagon, the altar placed at the intersection of the hospital’s cross-shaped plan so that the wards extended outward like symbolic arms of the cross. From their beds, patients could see and hear the liturgy, experiencing the healing of body and soul as a unified act.

Donato Bramante

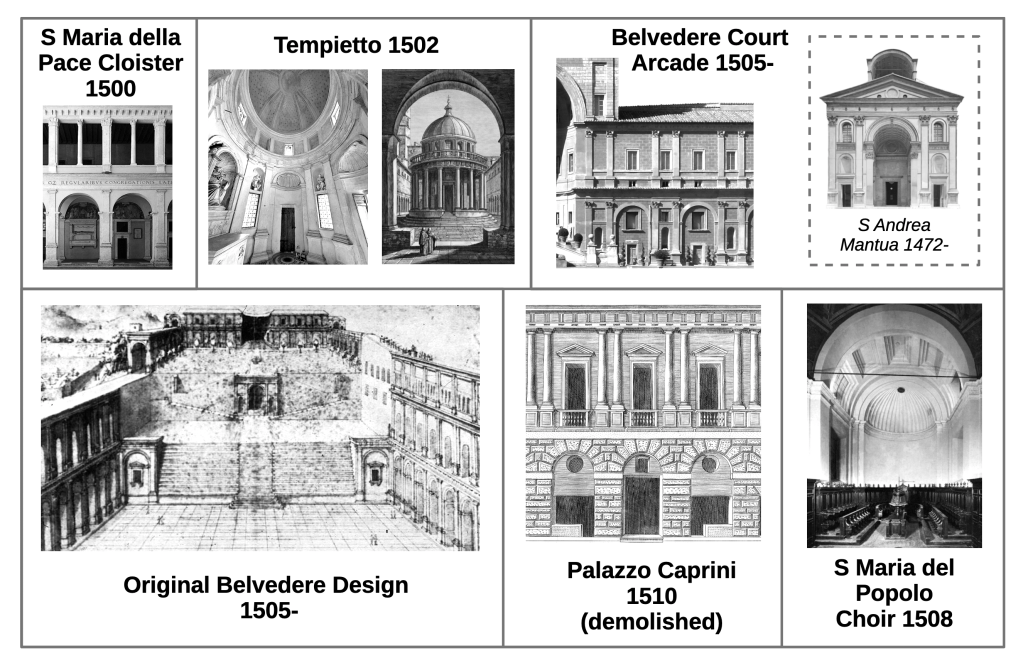

Thus far, I have not mentioned the names of the architects responsible for the buildings of fifteenth-century Rome. This is because most Roman architecture of the period resulted from close collaborations between ecclesiastical patrons and teams of lesser-known designers, unlike the landmark 14th and early 15th century architecture of Florence, which was defined by great artists such as Alberti and Brunelleschi. However, beginning in 1500, the arrival of the great Donato Bramante from Milan inaugurated the High Renaissance in Rome. One of his first commissions was the new cloister of Santa Maria della Pace (1500). For the ground-floor arcade, Bramante employed an arcade similar to the one at Palazzo Venezia—but substituted pilasters for columns. It was a composition that was widely admired for its geometric purity.

Bramante’s masterpiece, the Tempietto (1502), was inspired by circular antique temples such as the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. To this ancient prototype, Bramante added a balustrade and an upper arcade serving as a drum, surmounted by a small dome. The resulting composition embodied an ideal of classical harmony and became the prototype for countless domed buildings throughout Europe. With the Tempietto, Bramante moved beyond the regional Lombard style of his previous Milanese period to achieve a universal expression of classical beauty.

Bramante’s Belvedere Palace at the Vatican (1505-) has been so extensively altered that little of his original conception remains. Nonetheless, the elevation at the east end of the upper courtyard preserves his design. Its triumphal-arch motif, first introduced to Renaissance architecture by Alberti in Sant’Andrea, Mantua (1472-), and its monumental exedra are original to Bramante, although modified by later architects.

His Palazzo Caprini (1510-), though now lost, played a key role in the evolution of the classical urban façade. Bramante refined the balanced proportions seen at Palazzo Cancelleria, pairing columns more closely together in the Doric order and introducing finely rusticated masonry on the ground floor. This arrangement became a model for countless later Renaissance palazzi.

The choir of Santa Maria del Popolo is Bramante’s only surviving ecclesiastical work in Rome apart from the Tempietto. It preserves the purity of his original design, unaltered by later Baroque ornamentation. Bramante’s grandest Roman project—his plan for the new St. Peter’s Basilica—is addressed in Evolution of the Church Floor Plan, Part III, as part of an analysis of the evolution of its design across the 16th and 17th centuries.

Raphael

The great Renaissance painter Raphael made several significant architectural contributions in Rome. His Chigi Chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo (1513-) is essentially a miniature version of Bramante’s design for the crossing of St. Peter’s Basilica. The massive crossing piers at St. Peter’s are all that remain of Bramante’s original 1505 plan. The hemispheric domes of both Raphael and Bramante rest on octagonally arranged piers flanked by fluted pilasters, a motif first introduced at Bramante’s Tempietto (see figure 6), though there employed on a circular rather than an octagonal base.

Raphael’s Palazzo Vidoni–Caffarelli reinterprets the motifs of Bramante’s Palazzo Caprini. The ground story features rusticated stonework that emphasizes strong horizontal lines, while the upper stories employ the Tuscan order in place of Bramante’s Doric.

Raphael’s Villa Madama was unfortunately never completed. Its surviving curved garden loggia, built in the Ionic order, contains a richly decorated interior inspired by the ancient murals newly discovered in Nero’s Domus Aurea (c. 64 AD). The villa’s shallow domes recall the structural systems of the Baths of Diocletian and the Basilica of Maxentius, and also bear a resemblance to the vaulted construction at San Pietro in Montorio (see figure 3).

Early 16th c. Central Plan Churches

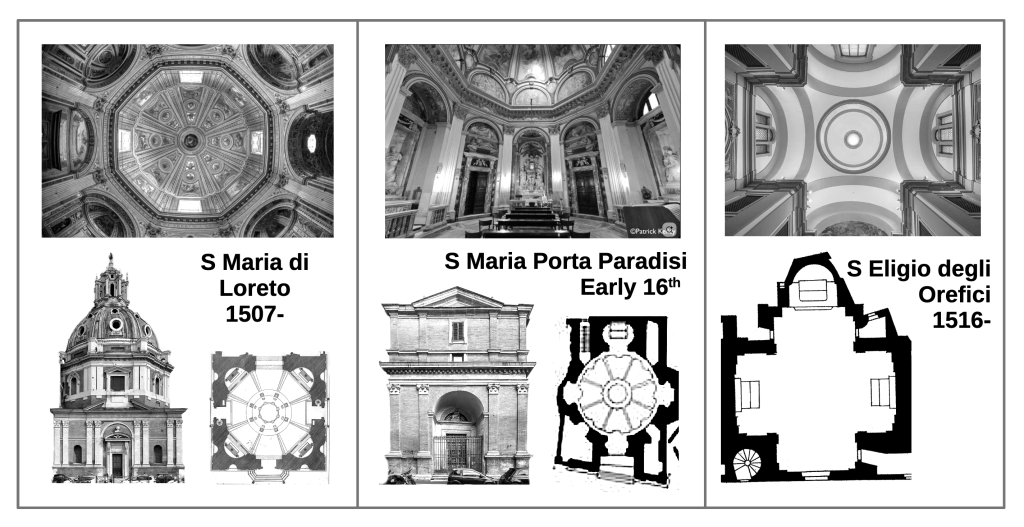

Apart from the great works of Bramante and Raphael, a number of smaller churches were built in Rome during the early sixteenth century, though they have not survived in their original form. The three discussed here reflect the period’s strong preference for centralized plans. Santa Maria di Loreto (begun 1507) and Santa Maria Porta Paradisi (early 16th century) both feature straightforward octagonal domes, inspired by Santa Maria della Pace (1478; see figure 3). Sant’Eligio degli Orefici (begun 1516) introduces a Greek-cross plan with very short arms—a design that became a prototype for many private family chapels later in the century.

Baldassarre Peruzzi

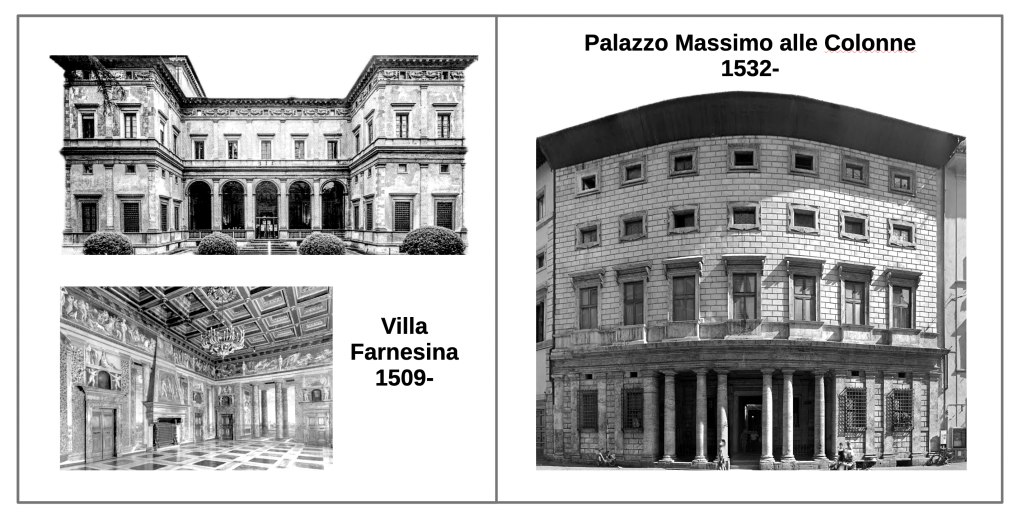

Another great Renaissance painter, Baldassare Peruzzi, made two major contributions to Roman architecture in the early sixteenth century: the Villa Farnesina (1509-) and the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne (1532-). The Villa Farnesina became the prototype for the U-shaped suburban villa, which replaces the traditional inner courtyard with a rear loggia opening directly onto a garden. This model spread throughout Europe through Sebastiano Serlio’s mid-sixteenth-century architectural treatises, which illustrated plans closely resembling that of the Farnesina. The villa’s façade abandons the double-columned arrangement popular in contemporary palazzi and returns to the single-pilaster divisions of Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai (see figure 4).

Peruzzi adorned the Farnesina with extensive mural decoration, including frescoes on its exterior walls which have since been lost. In the celebrated Stanza delle Prospettive, he demonstrates his mastery of linear perspective through an illusionistic painted loggia that opens onto an imagined landscape. This mural reflects Peruzzi’s background as a stage designer and anticipates the later Baroque fascination with optical illusion and spatial ambiguity.

At the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne (1532–), Peruzzi introduced a curved façade, a dramatic departure from the strict geometric order of the High Renaissance. This feature is often cited as an early landmark of Mannerism, which moved away from classical idealism toward more expressive, dynamic compositions. Peruzzi also gave the ground floor its own open loggia and replaced the compartmentalized window aedicules with fanciful frames.

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger

.Antonio da Sangallo the Younger contributed two major palazzi in the first half of the sixteenth century. The Palazzo Zecca (1530) features Bramante’s triumphal-arch motif from the Belvedere Palace (figure 6). This motif spans two stories, which turns its pilasters into a giant order. The scale of these upper stories dwarfs the rusticated ground floor, which is capped by an intermediary section that can be read either as part of the main floor or as the base of the second. The enormous blind arch on the top floors dominates the facade, producing an unbalanced composition. These eccentricities were moderated in Sangallo’s design for the Castro Mint, which achieves a more harmonious relationship between its parts.

Sangallo’s façade for the Palazzo Farnese departs significantly from earlier Renaissance precedents. The three stories are relatively equal in their designs, a marked contrast to the highly differentiated levels of earlier palazzi. As in Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne, the windows are not grouped into vertical bays, and the customary rustication of the ground floor has been eliminated. Variation between floors is limited to the window surrounds, which make generous use of consoles—one of Michelangelo’s favored motifs. The top story and monumental cornice are Michelangelo’s additions. While pronounced cornices had been a hallmark of Renaissance palace design since the fifteenth century, Michelangelo’s projects outward to an unprecedented degree, casting a deep shadow and heightening the building’s sculptural power.

Sangallo’s second-floor windows are framed by alternating segmented and triangular pediments, a motif derived from now-lost portions of the Temple of Jupiter, preserved in Palladio’s illustrations (Book IV, p. 43). In Michelangelo’s upper story, the pediments lack entablatures, and the arches intrude into their fields, a Mannerist touch. The façade’s corners are reinforced by prominent quoins, which became standard practice in classical multi-story architecture going forward.

The facade entrance opens into an impressive vestibule, a long barrel-vaulted corridor flanked by colonnades and side aisles that have been ornately coffered. The vestibule opens onto a courtyard with further architectural innovations. The bottom two floors were built by Sangallo- -the Doric order on the first floor and the Ionic on the second, as standardized by the superimposed orders on the Colosseum. The doubled moldings supporting each arch on the ground floor reflect an adjustment made when the aisle vaults were raised during construction. The windows of the second and the uppermost story are Michelangelo’s, as is the garlanded entablature separating them. The top-story windows feature segmental pediments supported on small brackets, creating the illusion that the pediments float above the frames, another Mannerist effect.

Sangallo also rebuilt the Church of Santo Spirito in Sassia (begun 1538) following its damage during the Sack of Rome (1527). The new design adopts a single-aisled basilican plan, signaling a return to longitudinal church architecture and a departure from the centralized forms favored earlier in the century. The church’s flat wooden ceiling revives the model of the early Christian basilica, an approach explored by Brunelleschi at San Lorenzo (begun 1418) but long resisted in Rome, where medieval vaulting remained the norm (see figure 1). Sangallo introduced barrel-vaulted side chapels in place of aisles—an arrangement employed by Alberti at Sant’Andrea, Mantua (1472-), which was in turn inspired by the barrel vaults at the secular Basilica of Maxentius (308-). Santo Spirito is thus a synthesis of different antique models: a flat-roofed nave recalling the early Christian tradition, and barrel-vaulted chapels derived from imperial Roman architecture—a union of sacred and secular forms.

Michelangelo’s Piazza Campidoglio

Apart from St. Peter’s Basilica, Michelangelo’s most significant architectural contribution in Rome was the redesign of the Piazza del Campidoglio. The original square contained the twelfth-century medieval town hall, the Palazzo Senatorio, and a fifteenth-century arcaded palazzo. Michelangelo reimagined the space by introducing two identical facades flanking the Senatorio, each turned inward at a slight angle to create an enclosed composition. At the center, he placed an oval pavement surrounding the ancient bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, transforming the irregular medieval site into a unified civic stage.

Michelangelo’s new façade for the Palazzo dei Conservatori introduced several important innovations. Most notable is the use of the giant order, with pilasters spanning two stories. The palazzo is also crowned with a balustraded cornice. While balustrades had appeared in the fifteenth century on porches—such as at the Villa di Poggio a Caiano (1480)—and on Bramante’s Tempietto (figure 6), Michelangelo was the first to employ them as rooftop ornamentation, a feature that would become a hallmark of later classical architecture. The ground-floor loggia is trabeated rather than arcuated, a rarity in multi-story Renaissance architecture. Although Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne (1532) also features a trabeated loggia, it only spans part of the facade and supported by tightly paired columns. By contrast, Michelangelo assigned each bay its own pair of columns, flanking every giant-order pilaster. This inventive system gave later Renaissance architects a new structural vocabulary, reused most famously in Maderno’s facade for St. Peter’s Basilica (1607-).

The Palazzo Senatorio was extensively remodeled as part of the same project. Its tower was shifted to the center, and a bifurcated staircase introduced, flanking a two-story porch composed on a triumphal-arch motif. The medieval masonry of the lower story was retained, giving the ground floor a rusticated flavor, while the upper stories were redesigned to match the accompanying palazzi.

Late Michaelangelo

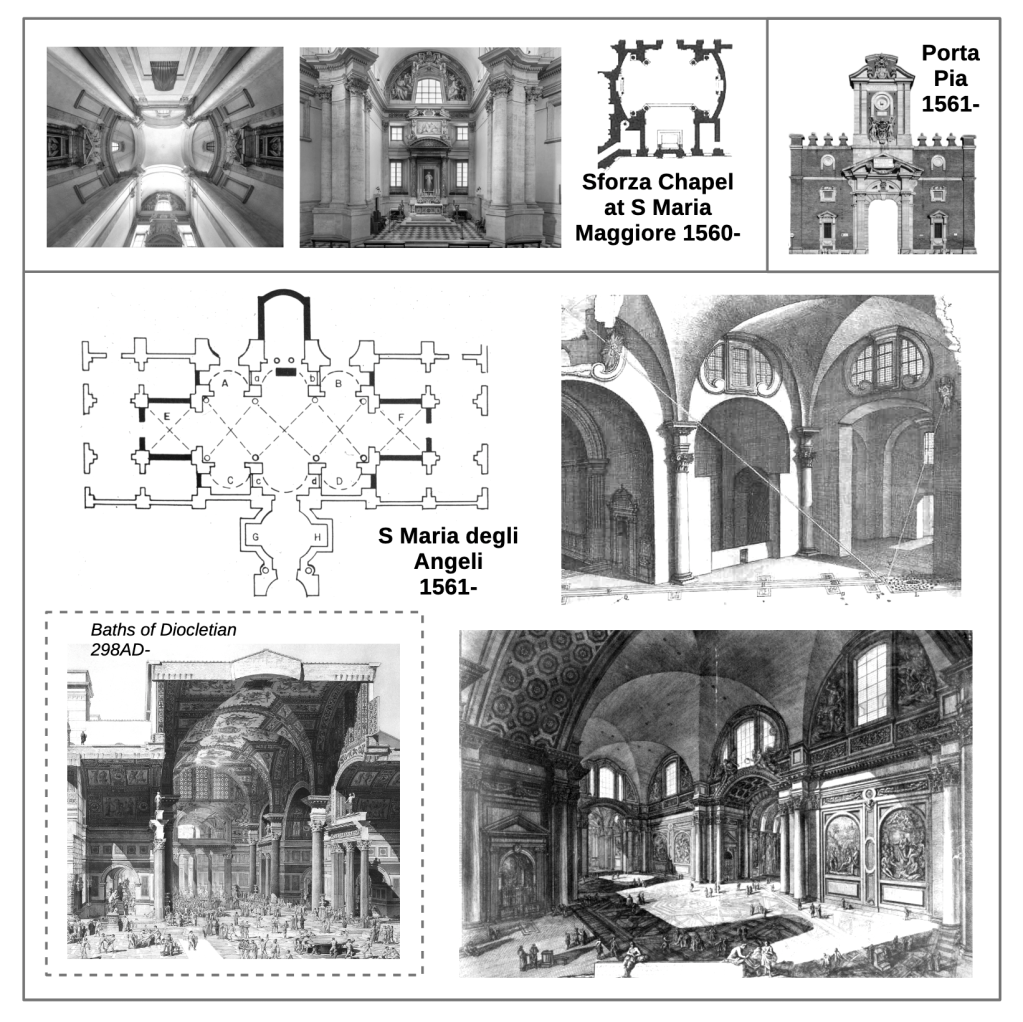

In the Sforza Chapel at Santa Maria Maggiore, Michelangelo departed significantly from the standard chapel prototype. The plan, nominally a Greek Cross, features flattened apsidal transepts flanking a central space. The crossing piers, articulated with enormous ressauts and free-standing columns, appear overly monumental within the enclosed interior. This device—placing free-standing columns adjacent to supporting piers—was one of Michelangelo’s architectural signatures, as seen on the ground floor of the Palazzo dei Conservatori. Abundant light animates the undulating curves of the monochromatic walls, which highlights the chapel’s sculptural qualities.

The Porta Pia (1561-) reveals Michelangelo at his most Mannerist. The portal’s complex composition includes a rusticated jamb surrounded by layered pilasters, an entablature capped by a flattened lunette, and a broken segmental pediment supported by volutes holding a garland—surmounted by yet another pedimented arch framed with consoles. Despite its obvious exuberance, the design was not whimsical; numerous surviving studies attest to Michelangelo’s deliberate compositional process.

Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri was constructed within the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian. The central portion of the Baths consisted of a longitudinal, three-bay vaulted hall known as the frigidarium. The obvious retrofit would have been to align the church’s nave along this central axis. Instead, Michelangelo reinterpreted the frigidarium as an extended transept. Then he built a new chancel projecting out from the center of the frigidarium, as indicated by the black-lined sections of the floor plan illustrated above (figure 12). This reorientation gave the building a more centrally planned character than it would otherwise have possessed.

Michelangelo’s original interior design was monochromatic, adorned only with low-relief classical detailing. As in the Sforza Chapel, this restraint emphasized the structural and sculptural elements of the architecture itself, allowing light and shadow to animate the massive Roman volumes. In the eighteenth century, however, the church was extensively altered: additional columns, sculptural ornament, and polychrome marble were introduced, fundamentally changing its character. Today, the interior resembles the grandeur of an ancient Roman bath more than the austere monument Michelangelo envisioned. His approach at Santa Maria degli Angeli likely reflects the same monochromatic ideal he originally intended for St. Peter’s Basilica—but one which his successors abandoned.

Pirro Ligorio and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola

The sixteenth century also gave birth to the elaborate aristocratic country estate, a building type that would reach its apotheosis in the Palace of Versailles (1623-). Many of the earliest examples have either not survived or have been extensively redesigned, but Rome preserves two outstanding mid-sixteenth-century examples: the Casino di Pio IV and the Villa Giulia.

The Casino di Pio IV was strongly influenced by renewed interest in ancient Roman villas, particularly Hadrian’s Villa (118-), with its intricate composition of landscaped gardens, pools, baths, and fountains. The architect Pirro Ligorio, best known as an architectural decorator specializing in Roman antiquities, belonged to a circle of Renaissance “antiquarians” who consciously revived the decorative vocabulary of ancient Rome. The buildings of the Casino serve primarily as showcases for ornamental richness evoking ancient themes rather than demonstrating the structural rationalism characteristic of earlier Renaissance palazzi.

By contrast, Vignola’s Villa Giulia (begun 1551) is a more architecturally substantial design, filled with Mannerist innovations. The central portion of the main façade is arranged in a triumphal-arch motif: its lower portion is heavily rusticated, while the upper level features apsidioles pierced by windows—an eccentric choice. The contrast between the exuberant central bay and the relatively restrained flanking sections heightens the sense of theatricality. Vingola also tops the upper-story windows with fanciful aedicules, a playful touch.

The triumphal-arch motif continues on the semi-circular rear façade of the main palace, articulated by elongated pilasters. The curved loggia’s ‘annular’ vault recalls those of ancient Roman mausolea such as Santa Costanza (350-).

At the far end of the complex lies the Nymphaeum, whose central section repeats the triumphal-arch motif, incorporating a serliana on the upper level and a curved arrangement of herms or caryatids on the lower. These sculpted figures used as structural supports anticipate a motif that would become a favorite of Baroque architects.

Domenico Fontana and Late Renaissance Architecture

Late sixteenth-century Roman architecture was characterized by both conservatism and eccentricity. The elevations of Domenico Fontana’s Lateran Palace (begun 1586) closely resemble those of the Palazzo Farnese, despite being constructed more than forty years later. By Renaissance standards, such a prestigious commission might have been expected to break new ground, yet Fontana’s design remains firmly traditional. The façade of the Palazzo Borghese continues motifs introduced earlier at Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne, though its courtyard presents a genuine innovation for Rome—the use of paired columns. This feature had long been popular in Lombardy, but it failed to gain traction in central and southern Italy.

Fontana’s ventures into more experimental territory appear in his designs for the Vatican Library and the Sistine Chapel at Santa Maria Maggiore, where the underlying structural clarity becomes obscured by excessive ornamentation.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Renaissance architecture in Rome had reached an impasse. The rational principles of classical design had been codified in treatises such as Vignola’s Five Orders, yet simultaneously complicated by the flood of ancient fragments and details published by antiquarians like Pirro Ligorio. The Renaissance pursuit of a reborn classical age thus revealed an inherent contradiction between idealism and archaeology. It would take the Baroque reawakening of the seventeenth century to resolve that tension and restore new vitality to Roman architecture. That transformation will be the subject of my next post.

Leave a comment