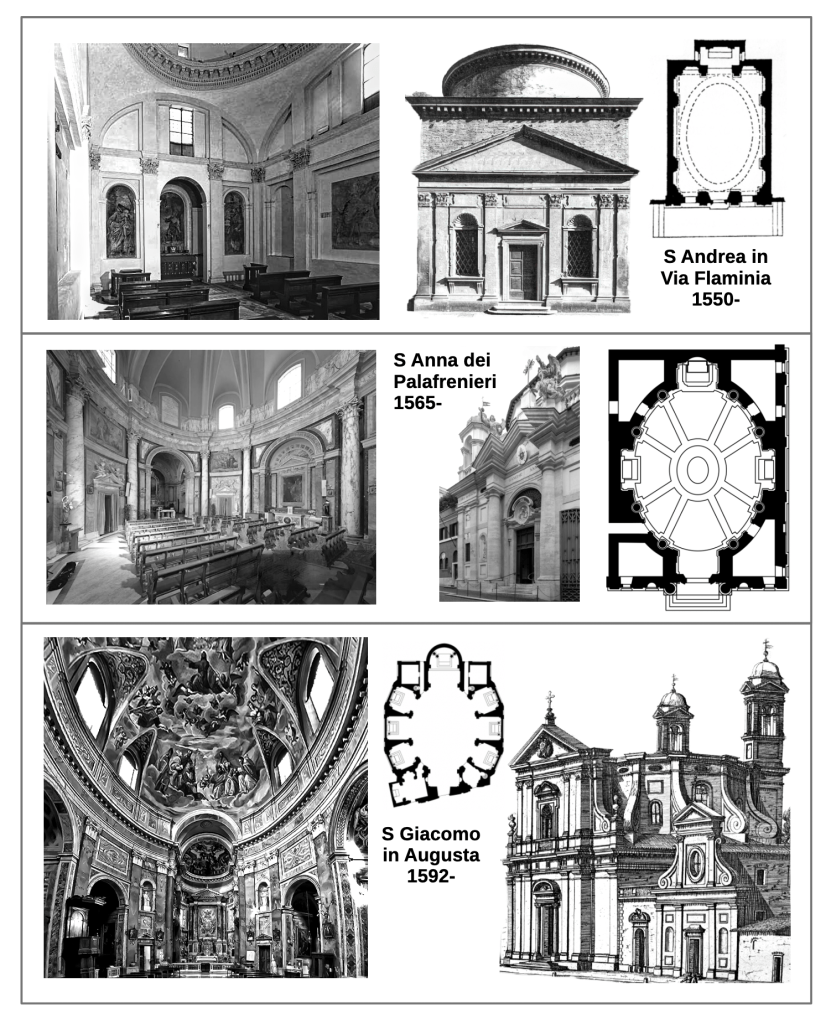

Early Ovals: Vignola and da Volterra

The oval is the central motif of Baroque architecture. Renaissance architects favored the circle, which they saw as the most perfect geometric form. Baroque architects challenged ideals of Platonic perfection and classical harmony, pursuing a theatrical and emotive architectural language grounded in complex geometries. The three churches illustrated above were among the earliest to adopt oval plans during the late Renaissance. Here, the choice of oval likely reflects a compromise between the centralized plans dominant in the early sixteenth century and the longitudinal plans favored later by counter-reformational patrons.

At the church of Sant’Andrea on the Via Flaminia, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola employed an oval floor plan. But apart from this, the church adheres to traditional Renaissance geometry. Its exterior recalls a miniature Pantheon. Vignola’s later Sant’Anna dei Palafrenieri (1565-) also uses an oval plan, but unlike Sant’Andrea, its interior walls follow the curve of the dome. Its vaults spring from eight irregularly spaced columns rather than from four pendentives, as at Sant’Andrea. The façade of Sant’Anna also departs dramatically from the serene classicism of Sant’Andrea, featuring pronounced ressauts and a broken pediment.

Francesco da Volterra’s San Giacomo in Augusta (1592-) adopts an oval plan similar to that of Sant’Anna but adds six regularly spaced, barrel-vaulted chapels around the perimeter and replaces Vignola’s columns with pilasters. Its entablature forms an unbroken oval up to the chancel apse, emphasizing elongated horizontal lines—unlike Vignola’s entablature, which is interrupted by ressauts above each column.

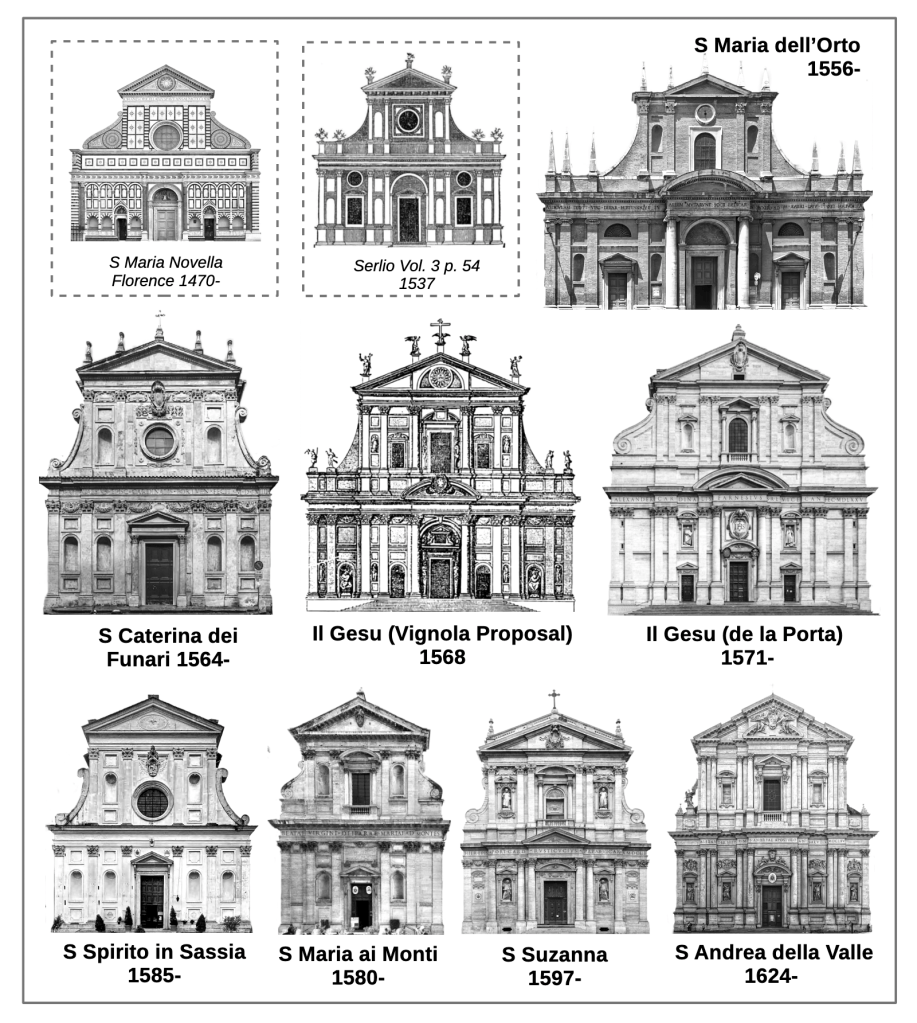

The Il Gesù Facade Type

During the late Renaissance and early Baroque period, a new façade type emerged that would shape Catholic architecture for more than a century. Its key motifs were codified in a façade designed by Giacomo della Porta at the influential Jesuit mother church, Il Gesù (1571-). It featured a two-story composition with large scrolls flanking the upper story, concealing the buttresses that supported the barrel-vaulted nave. The design had precedents in Alberti’s façade for Santa Maria Novella (1470-) and in Sebastiano Serlio’s idealized façade drawing of 1537.

Shortly before della Porta completed Il Gesù, Vignola built the façade of Santa Maria dell’Orto (1556–) and submitted a similar proposal for the Il Gesù façade (1568). These structures drew on Serlio’s model but introduced new variations: they interrupted the entablature with a central, segmentally pedimented portal and eliminated the prominent circular window, replacing it with balanced arrangements of arcades, panels, and aedicules. Around the same time, Guidetto Guidetti designed a similar façade for Santa Caterina dei Funari (1564-). Unlike Vignola’s proposal, Guidetti’s retained the oculus, left the entablature uninterrupted, and incorporated elaborate flanking scrolls. Della Porta’s façade for Il Gesù seems to combine traits from both Vignola’s 1568 proposal and Guidetti’s 1564 façade.

In the century that followed, hundreds of Gesù-like façades were built throughout the Catholic world. Rome alone contains many examples inspired by della Porta’s prototype. Santo Spirito in Sassia’s façade (1585-) revisits Guidetti’s arrangement at Santa Caterina. Della Porta’s Santa Maria ai Monti (1580-) offers a simplified and narrower version of Il Gesù, with an unbroken entablature. At Santa Susanna (1597), the architect Carlo Maderno introduced a more compact version of Il Gesù, using columns in place of pilasters on the lower story to create a more dynamic effect.

Sant’Andrea della Valle, begun in 1624 to a plan by Maderno but completed by Carlo Rainaldi in 1667, represents an even more richly articulated design than Santa Susanna. Its façade incorporates multiple projecting and receding planes and several sets of paired columns. A comparison with Rainaldi’s façade for Santa Maria in Campitelli (1659, figure 13) shows that at Sant’Andrea della Valle he moderated the sharply angular, boldly projecting vocabulary of his High Baroque style to reflect the spirit of Maderno’s Early Baroque plan. The result is a façade that blends Maderno’s earlier lyrical classicism with Rainaldi’s later, more theatrical High Baroque sensibility.

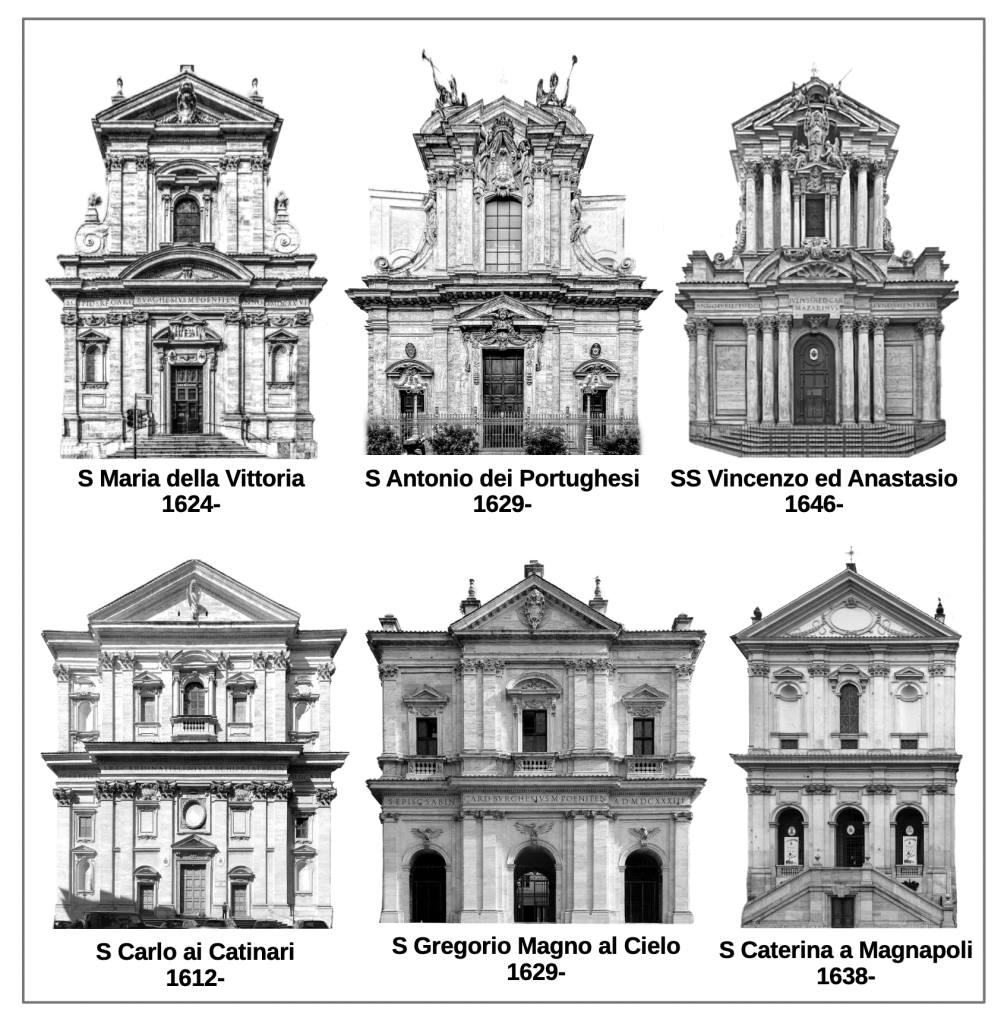

Further Development of the Il Gesù Facade Type

In the early seventeenth century, other Gesù-style façades also began to undergo Baroque transformations. Santa Maria della Vittoria (1624-), designed by Giovanni Battista Soria, adheres closely to the Gesù prototype and shows a particular affinity with Santa Susanna. Its main innovation is the use of a broken pediment on the lower story, a motif derived from Vignola’s unbuilt 1568 proposal for Il Gesù.

With Sant’Antonio dei Portoghesi, however, Martino Longhi the Younger radically reimagined the Gesù model. Although the façade retains the basic Gesù motifs, Longhi layers pilasters and their entablatures in mounting tiers, creating an intensely dramatic effect. This dynamism is heightened by the prominent sculptural program, especially the trumpeting angels crowning the façade. At Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio, Longhi produced a comparable design but replaced the pilasters with free-standing columns, amplifying the sense of movement and depth even further.

By contrast, the early seventeenth-century façades of Giovanni Battista Soria are more conservative and employ another established façade type: two stories of equal width surmounted by a pediment. Like the Gesù prototype, these façades typically consist of three to five bays arranged hierarchically around a dominant central bay, but they maintain a more restrained architectural language.

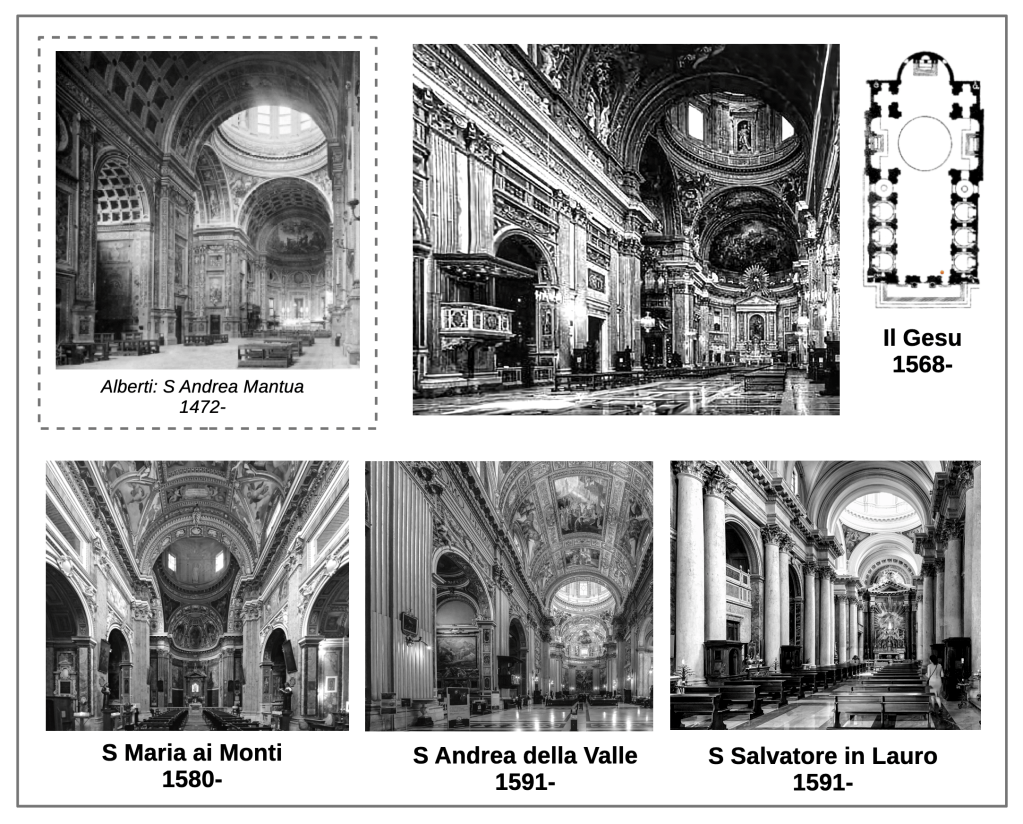

The Il Gesù Interior

Before moving further into the High Baroque era, let’s examine the development of the interiors of late sixteenth-century churches. Vignola’s interior of Il Gesù conformed closely to the new standards outlined by the counter-reformational Council of Trent (1545-63), including a return to longitudinal plans with wide, aisle-less naves flanked by compartmentalized chapels. This plan shifted the emphasis toward preaching to large congregations. Il Gesù’s transepts were shortened, and a circulation path around the central crossing allowed visitors to access the surrounding chapels without disrupting ongoing masses. Architecturally, the church was heavily modeled on Alberti’s Sant’Andrea in Mantua (1472-). However, Vignola introduced several innovations: lunette windows were added to the nave to admit more light, and the arches opening into the chapels were lowered. The chapels’ barrel vaults were also replaced with individual domes, which improved acoustics.

Other late sixteenth-century churches followed this general pattern with their own subtle variations. Santa Maria ai Monti (1580-) and Sant’Andrea della Valle (1591-) both broke up the long, uninterrupted horizontals of Il Gesù’s nave entablature by introducing a series of projecting ressauts of varying complexity, helping to establish a more regular architectural rhythm throughout the nave. San Salvatore in Lauro (1591-) replaced pilasters with pairs of free-standing columns—a trend also seen on the façade of Santa Susanna (1597; see figure 2). This arrangement had earlier been explored in Michelangelo’s remodeling of Santa Maria degli Angeli (1561-), and it would become increasingly common in the decades to follow.

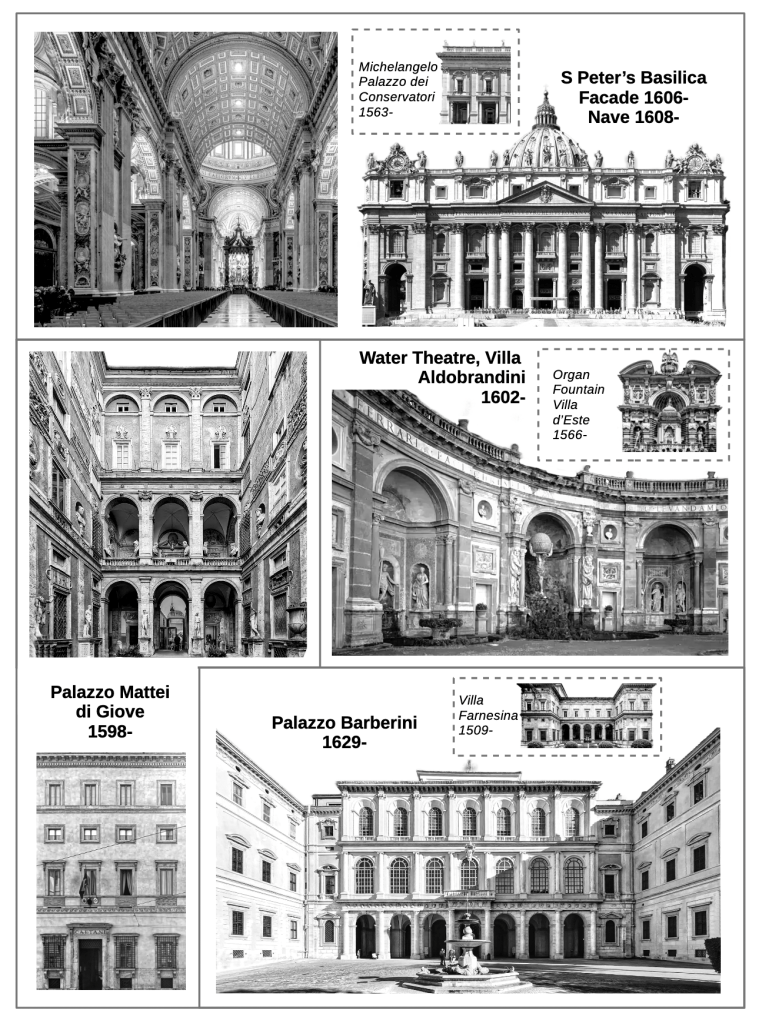

Carlo Maderno

Carlo Maderno is often viewed as the last major architect of the Late Renaissance and an important transitional figure leading to the High Baroque era of the early and mid 17th century. In 1606 he began completing the façade and nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. The nave elevation follows the pattern established at Santa Maria ai Monti but on a much larger scale. His façade replicates the design language developed by Michelangelo for the exterior of the rest of the basilica: giant orders topped by an attic story and balustrade. Maderno also flanked the entrance doors with smaller sets of columns, a compositional feature introduced by Michelangelo at the Palazzo dei Conservatori (1563).

Maderno’s secular works highlight a trend away from the Mannerist eccentricities of the late Renaissance, toward the more historically informed classicism of the early Baroque. The exterior of the Palazzo Mattei di Giove (1598– ) reflects the conservative character of the period, with simple astylar windows arranged in a manner similar to the Palazzo Farnese of the 1540s. Inside, the courtyard uses arcuated piers based on Bramante’s cloister at Santa Maria della Pace (1500), though with more decorative sculpture. His Water Theatre at the Villa Aldobrandini (begun 1602) follows Mannerist precedents such as the herms at the Villa d’Este’s Organ Fountain (1566), but Maderno softens the Mannerist elements with his more restrained classicism. His Palazzo Barberini (1629– ) adapts the U-shaped garden villa type, first used at the Villa Farnese (1509– ), to an urban setting.

After Maderno, architectural practice in Rome changed significantly. In the seventeenth century, a new kind of architecture emerged, shaped by strong individual artistic personalities. This shift was supported by the popes of the period: Urban VIII (1623–44) and Innocent X (1644–55) allowed greater freedom of expression than the more conservative, Counter-Reformation stance of Paul V (1605–21). Centralized church plans became common again, and architects adopted more theatrical approaches to space and decoration. These conditions allowed the major Baroque architects—such as Borromini, Bernini and Cortona—to develop the distinct styles that defined the High Baroque.

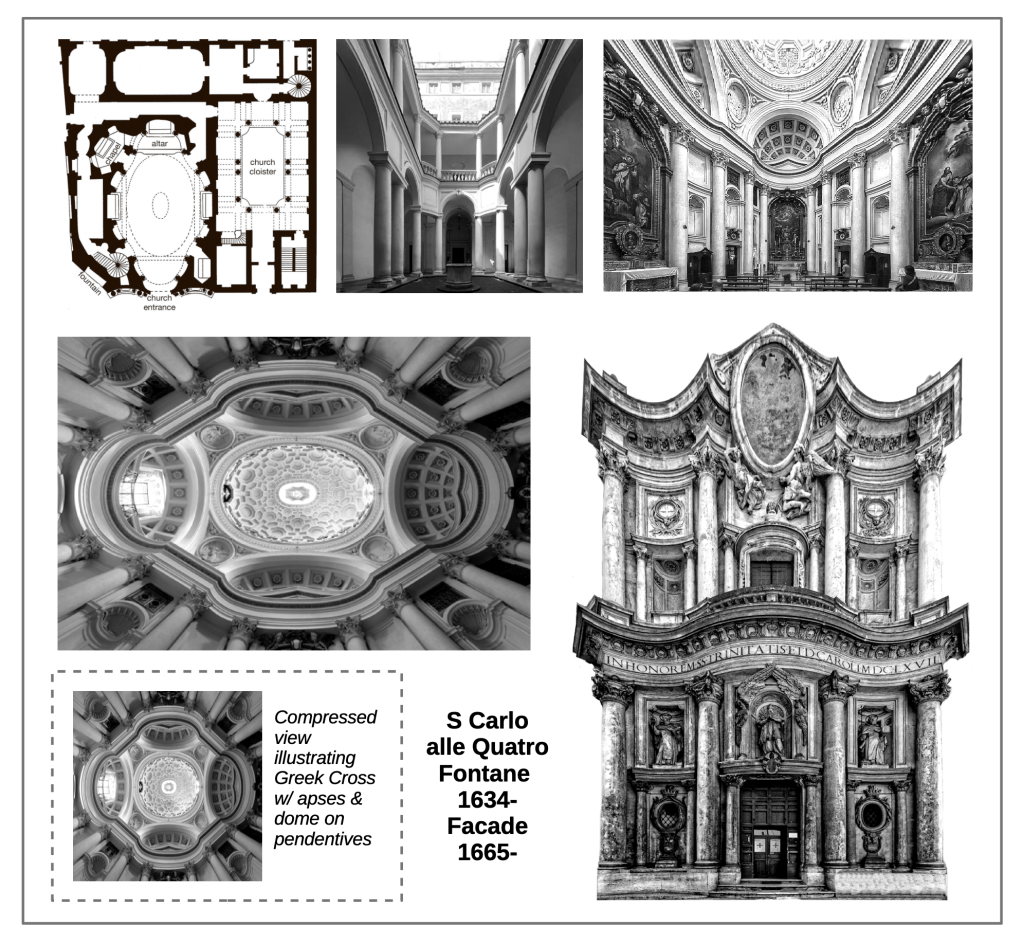

Francesco Borromini’s St. Carlo alle Quatro Fontane

Borromini was the most innovative and unconventional of the early Baroque architects. One of his first major commissions was the courtyard for the convent of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. Its unexpected design—an elongated octagon with arcades carried on paired columns—was so successful that the convent asked him to design a new church as well, which was to become one of the defining works of Baroque architecture.

The interior features a groundbreaking composition of interlocking convex and concave forms that can be difficult to interpret at first glance. However, when the dome is visually “compressed” back into a circle (as shown in the figure above), the underlying geometry becomes clear: a simple Greek cross with shallow apses and a dome on pendentives. Borromini elongated the cross and stretched its edges so thoroughly that the conventional form disappears, producing a space that feels entirely new. The façade is equally original. Its wall surface follows a wave pattern, and the two stories break from their traditional alignments: the lower story is convex at the center, while the upper story is concave.

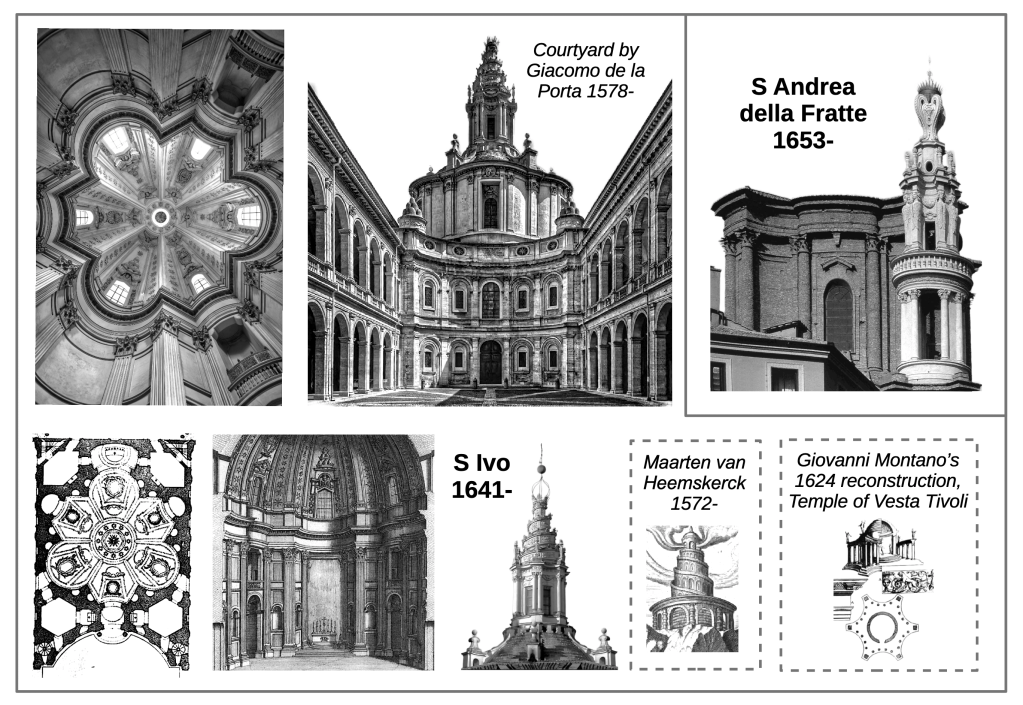

Borromini’s St. Ivo

At Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, Borromini used a central hexagon, with each of the six sides modified in an alternating arrangement of convex and concave forms. Some historians argue that Borromini’s choice of the hexagon was inspired by the shape of the Barbarini bee, the emblem of the family for whom he built the chapel. The end result of this compositional choice is a bewildering array of complex spacial forms on the interior of the chapel. The exterior is also unusual. Instead of highlighting the dome, Borromini concealed it beneath a tower. Centralized structures with concealed domes were common in Lombard architecture, such as Bramante’s Sacello at Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan (1476– ), but rare in Rome. Borromini modeled his tower on ancient Roman central-plan temples, which he knew from Giovanni Battista Montano’s 1624 reconstruction of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. Montano’s drawings include hexagonal, concave recesses that may have inspired the overall hexagonal plan of Sant’Ivo. Borromini topped his tower with a spiral, an effect he repeated at the church of St. Andrea della Fratte (1653-). The inspiration for this spiral form may have come from fanciful early modern illustrations of ancient ziggurats, such as Maarten van Heemskerck’s 1572 engraving of the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

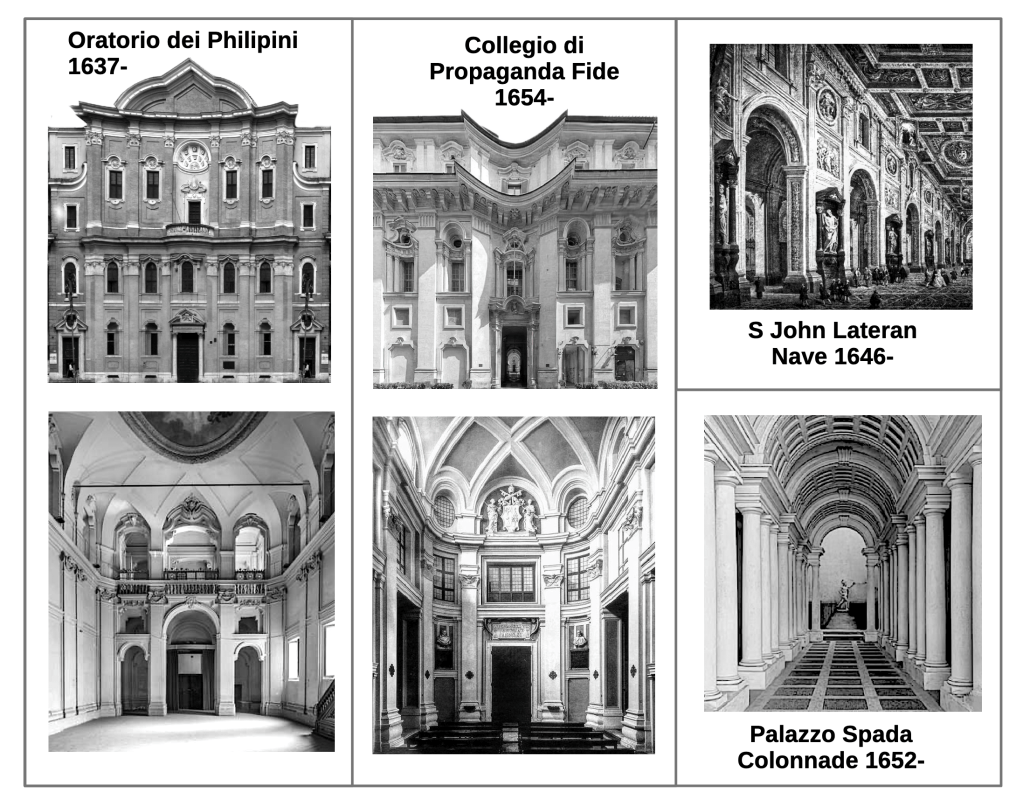

More Borromini

Borromini also designed two rectangular chapels: the Oratorio dei Filippini (1637– ) and the Collegio di Propaganda Fide (1654– ). In both, pilasters rise from the floor, continue through a giant order, and extend onto the ceiling as decorative bands. At the Collegio, these bands form a continuous framework with very little intervening wall surface, recalling Gothic structural principles. The building also uses Michelangelo’s combination of giant and secondary orders, first developed at the Palazzo dei Conservatori.

The façade of the Oratorio employs convex and concave lines similar to San Carlo, but distributed more subtly across seven bays instead of three. It is topped by a distinctive pediment that mixes curved and straight lines and includes smaller subsidiary pediments. The façade of the Collegio shares its broad, multi-bay arrangement, reflecting its dual function as both church and palazzo entrance. Here Borromini abandons many classical conventions: the capitals of the giant pilasters are reduced to simple notched blocks, the cornice projects sharply but lacks a full entablature, and the second-floor windows have concave entablatures that echo the concavity of the central bay. As one of Borromini’s last works, it shows his shift away from sculptural ornament toward bold massing and striking contrasts.

Borromini’s redesign of the nave of San Giovanni in Laterano (1646– ) addressed the structural failure of the ancient basilica. Because Innocent X insisted on preserving the old church, Borromini encased each pair of existing nave columns within a long rectangular pier flanked by giant pilasters. He intended to replace the ceiling with a barrel vault, but the cost proved too high; Daniele da Volterra’s Renaissance ceiling of 1564 was left in place.

At Palazzo Spada (1652), Borromini was commissioned to design a colonnade that would appear much longer than it actually was. He achieved this effect by gradually narrowing the passageway and reducing the height of the columns, creating a powerful forced-perspective illusion. Similar optical experiments appear in his dome designs. At San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, for example, the coffers decrease in size as they rise toward the apex, making the dome seem taller than it is. These techniques anticipated the optical illusions Bernini would later employ at the Vatican.

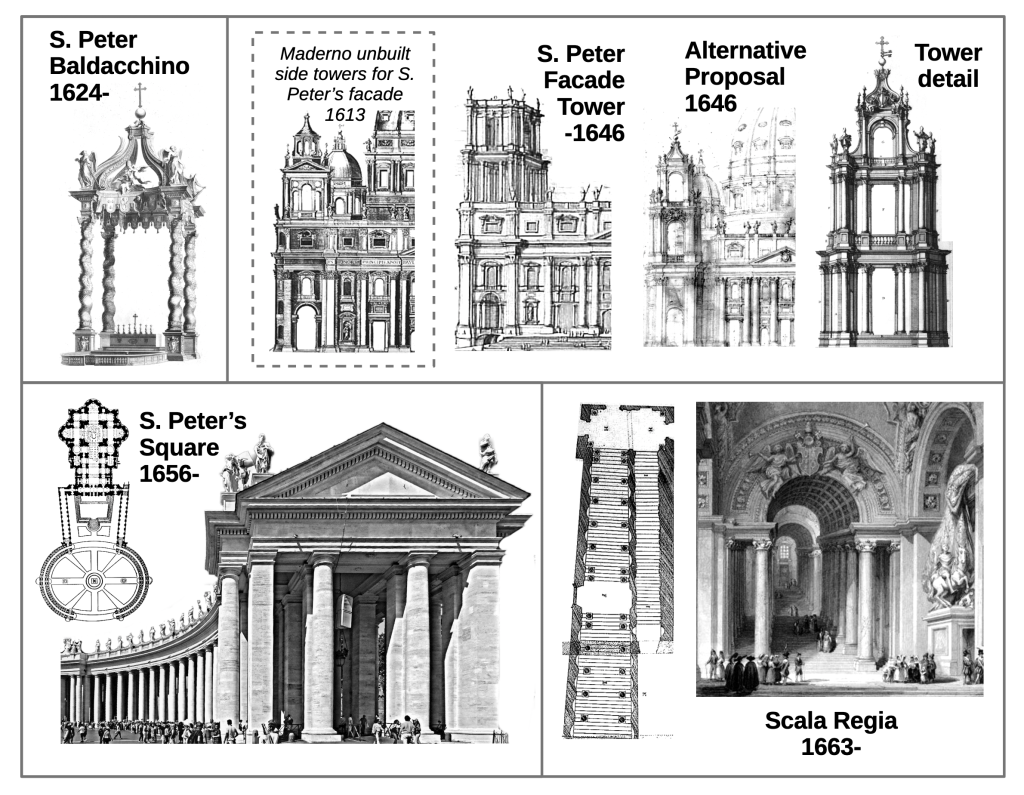

Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Works at the Vatican

Gian Lorenzo Bernini is best known as a sculptor, and he brought a sculptor’s approach to his architectural work. One of his first major projects was the Baldacchino at St. Peter’s Basilica (1624– ), a highly ornate canopy that stands as one of the great decorative achievements of the Baroque. Maderno’s 1613 façade for St. Peter’s had been designed with platforms for two towers. Without the towers, the façade appeared excessively wide in relation to the dome behind it. Bernini designed an elegant three-tiered tower for each side, but construction stopped at the second tier when structural weaknesses were discovered. He then proposed placing towers in front of the façade, but this plan was also abandoned. The result was a façade that was too long, and also seemed to dwarf the dome.

To address this imbalance, Bernini designed the great piazza in front of St. Peter’s, using an elliptical colonnade to frame the viewer’s perspective. The piazza encourages visitors to stand at a distance from which the dome can be properly appreciated. Like Borromini, Bernini employed tapering in parts of the colonnade to increase the perceived depth. He used a similar technique in the Scala Regia at the Vatican, where the staircase narrows as it rises to enhance the illusion of length.

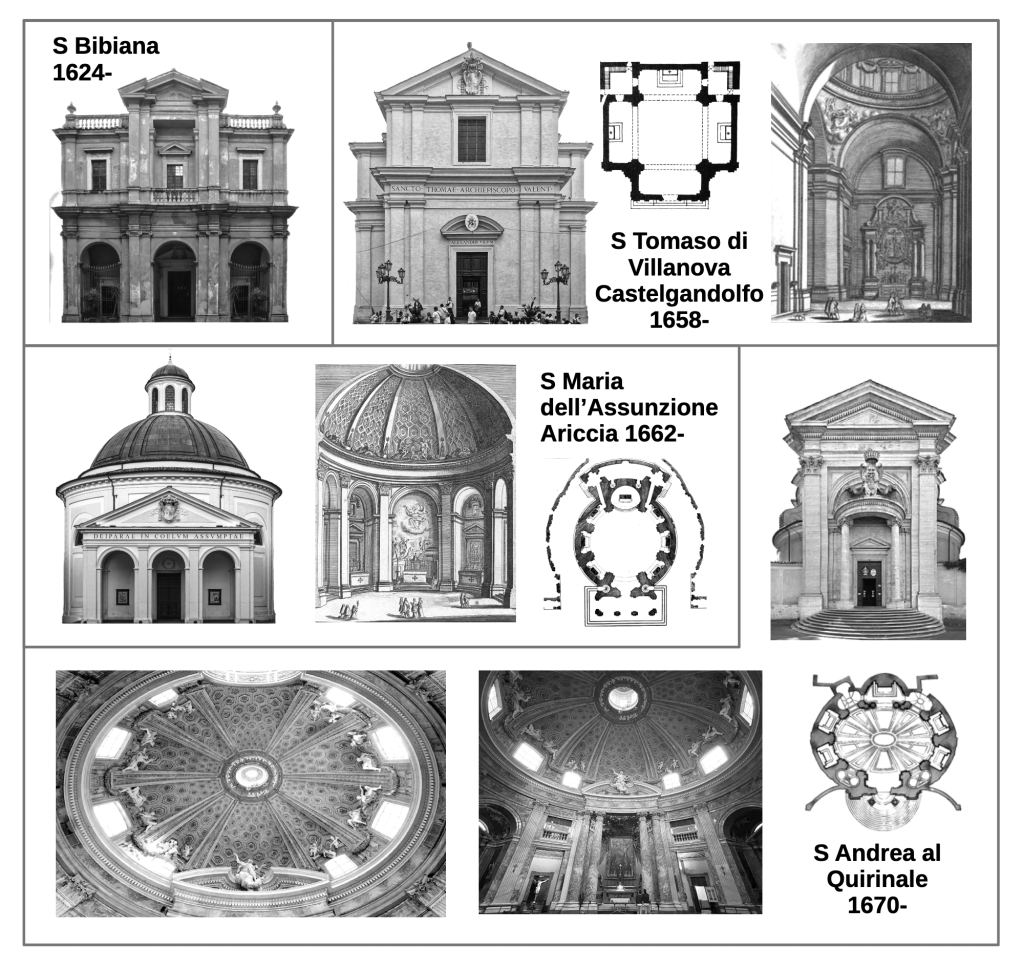

Bernini’s Churches

Bernini’s church façades tend to be more conservative than Borromini’s. The façades of Santa Bibiana (1624– ) and San Tommaso di Villanova (1658– ) follow a straightforward classical approach similar to Soria’s San Gregorio Magno al Celio (1629). Even so, Bernini introduced distinctive elements. At Santa Bibiana, a large central aedicule is placed above the main entablature, giving added emphasis to the center. At San Tommaso, Bernini revived the early sixteenth-century two-story Greek-cross type used in Renaissance buildings such as San Eligio degli Orefici (1516– ). Its façade also resembles earlier like Santa Maria Porta Paradisi (see Evolution of Renaissance Architecture in Rome, figure 8).

Santa Maria dell’Assunzione (1662– ) was designed during a period when Bernini was working on proposals to restore the Pantheon. He believed that the original Pantheon consisted of a simple domed cylinder with a pedimented portico, and he used this idea as a model for Santa Maria. A comparison with Vignola’s Sant’Andrea on the Via Flaminia—also inspired by the Pantheon—illustrates how differently each architect interpreted the ancient monument (see figure 1). The interior of Santa Maria consists of eight nearly identical bays, minimizing emphasis on the main altar, a choice reflecting Bernini’s assumption that the Pantheon had originally been articulated in a uniform way.

Bernini also experimented with an oval plan at Sant’Andrea al Quirinale. In this case, the oval is placed along the transverse axis rather than the longitudinal one, due to site restrictions. Bernini kept the visual focus on the main altar by minimizing the transverse axis with a central pilaster rather than a full chapel. The chapels beside the main altar receive less natural light, further emphasizing the central aedicule. This aedicule is given additional weight through paired free-standing columns, and the sculpture of St. Andrew appears to break through its pediment into the dome above. The dome itself is low, but Bernini disguised this by using ribs and coffers that are illusionistically foreshortened. Although ribs and coffers traditionally served structural purposes and were not used together, Pietro da Cortona combined them earlier at Santi Martina e Luca (1635), a precedent discussed later in this article.

The façade of Sant’Andrea is built around a single large aedicule that encloses a smaller rounded portico. Its convex form echoes both the interior dome and the curved staircase beneath the church. The result is a composition that is simply organized, yet surprisingly innovative.

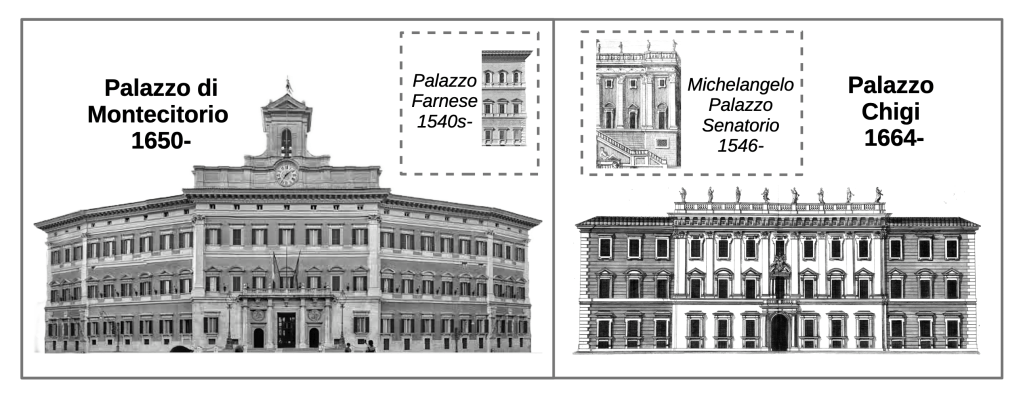

Bernini’s Palazzi

Bernini also designed two important palaces: Palazzo Montecitorio (1650– ) and Palazzo Chigi (1664– ). Palazzo Montecitorio follows the simple elevations established at the Palazzo Farnese in the 1540s, but adapts them to the curvature of the street in a series of five angled planes. The central tower was added later by Carlo Fontana. At Palazzo Chigi, Bernini derived the central bays from Michelangelo’s Palazzo Senatorio, while the side bays follow the Farnese pattern, complete with side quoins.

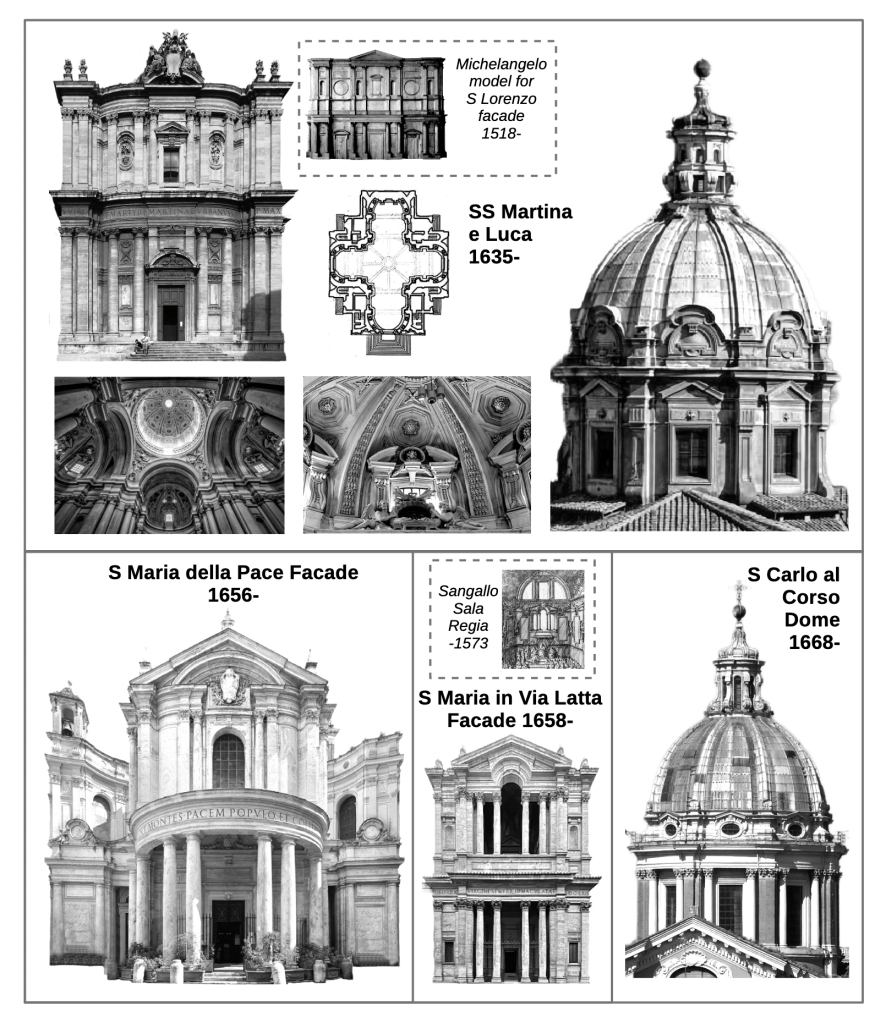

Pietro da Cortona

Pietro da Cortona was the third major architect of the High Baroque period and also one of Rome’s most influential painters. His first significant architectural work was Santi Martina e Luca (1635– ). The church uses a Greek-cross plan, and its interior walls are densely organized with columns and pilasters, leaving little room for additional decoration. Each of the many columns has an Ionic capital, creating a repeated scroll motif that functions almost like a continuous decorative band. Although the lower level is relatively plain, the upper portions contain a wide range of Mannerist decorative elements in the Florentine style—little actual sculpture, but numerous varied motifs ranging from angular to rounded forms. The dome of SS. Martina e Luca was the first to combine coffers with ribs, a hybrid system that later appears in Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (1670– figure 10).

The façade of SS. Martina e Luca combines sharp, angular shapes with softer, rounded ones. The central bays project gently outward, while the outer bays hold the façade within a rigid rectangular frame. The façade is also disproportionately large compared to the entrance arm it fronts. Michelangelo’s unbuilt façade design for San Lorenzo in Florence (1518– ) shared this characteristic; both works treat the façade as an architectural statement within the wider urban context rather than as a direct reflection of the building behind it.

At Santa Maria della Pace (1656– ), Cortona repeated the convex motif of SS. Martina e Luca in the upper story, crowning it with an angular pediment enclosing a segmental one—a Mannerist device with Michelangelesque origins but rare in Rome at the time. The lower level features a projecting semicircular portico, a motif later used by Bernini at Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (1670– ) and by Christopher Wren at St. Paul’s Cathedral (1675– ) It later became a popular neoclassical motif. The convex center is flanked by concave wings, an interplay of forms also used extensively by Borromini at San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1665– ). Cortona designed the adjacent palazzi as well, transforming the square into an urban theatrical setting focused on the church façade.

At Santa Maria in Via Lata, Cortona returned to the two-story arrangement used at SS. Martina e Luca, but without the curved forms. Here, the outer panels recede rather than project, likely due to the constraints of the narrow street. He also set aside many of his earlier Mannerist tendencies, using a simple columned portico on the ground floor and a loggia with a Serliana (Palladian) motif on the upper story. The Serliana is crowned by a pediment, a form with precedents in both ancient architecture and Renaissance works, such as Sangallo’s Sala Regia (-1573).

Cortona’s last major architectural work, the dome of San Carlo al Corso (1668– ), shows a further move away from Mannerism toward a more restrained classicism. This can be seen by comparing it with the earlier dome of SS. Martina e Luca. Although more classical in tone, the dome still contains important innovations, especially in the drum: eight large brick pilasters are paired with two smaller marble columns, creating a harmonious polychromatic effect. The attic above the drum includes more ornament, but it is restrained compared to the exuberant decoration of his earlier work.

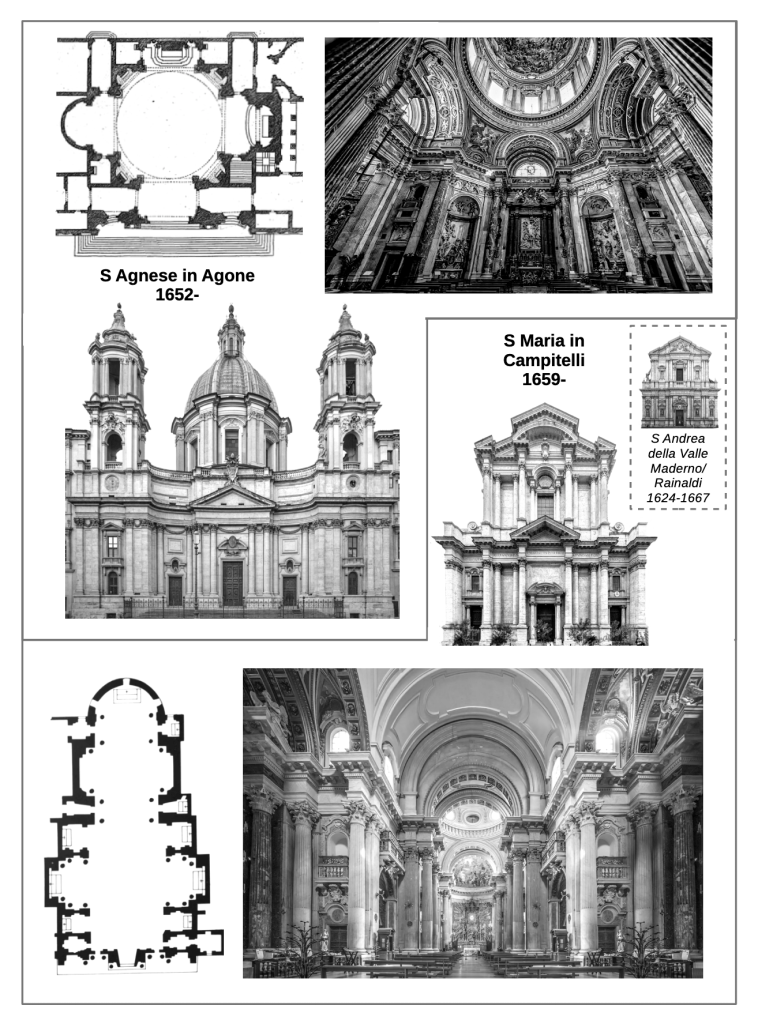

Carlo Rainaldi and Sant’Agnese in Agone

Sant’Agnese in Agone (1653–72) was designed by several major architects, including Borromini, Bernini, and Carlo Rainaldi. Rather than separating their contributions, it is most useful to view the church as a collaborative project that reflects the artistic values of the High Baroque. Like many important Baroque churches, it is based on a centralized plan—in this case, a Greek cross. The transept apses, however, are longer than the chancel apse, giving the floorplan a slight oval orientation.

Sant’Agnese can be interpreted as a response to shortcomings at St. Peter’s Basilica. At St. Peter’s, Maderno’s large façade and extended nave obscure the dome when viewed from the piazza. His plan originally included two towers that would have visually framed the dome, but these were never completed. At Sant’Agnese, the façade stands directly in front of the Greek-cross plan, leaving the dome clearly visible. The façade curves outward where it meets the two towers, which effectively draw attention to the central dome—achieving what Maderno intended at St. Peter’s. Both the dome and towers feature prominent ressauts that reinforce one another and contribute to the unity of the exterior.

Inside, the church has a strong sense of verticality. The height of the interior is much greater than its width, and the tall drum with large windows further emphasizes the upward direction of the space.

Sant’Agnese became one of the most influential churches of the period, helping popularize the two-towered Baroque façade in German-speaking regions. Christopher Wren modeled the towers of St. Paul’s Cathedral on those of Sant’Agnese, and this feature later became a hallmark of the Edwardian revival of Wren’s work, often called the “Wrenaissance.”

Carlo Rainaldi’s other major church was Santa Maria in Campitelli (1659– ). Rainaldi’s initial plan called for an enormous oval that would span the entire length of the church, but the difficulty of vaulting such a space led him to revise it. The final design uses a long nave with broad oval proportions, defined by expanding sets of chapels on each side. This unique plan risked drawing attention away from the high altar and toward the side chapels. Rainaldi countered this by flooding the chancel with light and by using two dozen large free-standing columns arranged in such a ways as to direct the focus toward the altar. His use of free-standing columns builds on earlier precedents, such as San Salvatore in Lauro (1591, figure 4) and Michelangelo’s transformation of the Baths of Diocletian into Santa Maria degli Angeli (1561).

For the façade, Rainaldi returned to the Il Gesù prototype, which was well-suited to fronting longitudinal churches with side chapels. The overall proportions resemble those of Santa Susanna and related models (figure 2), but the experience is transformed by Rainaldi’s sharply projecting ressauts. Unlike the curving forms used by many High Baroque architects, Rainaldi relied on strong, angular projections. His approach can be compared with Sant’Andrea della Valle (figure 2). That façade was begun by Maderno in the Il Gesù style (1624– ) and completed by Rainaldi. When compared with Santa Maria in Campitelli, Sant’Andrea’s ressauts appear much softer. The abrupt projections at Campitelli were softened at Sant’Andrea by layering the consecutive sets of pilasters.

Rainaldi’s Later Works

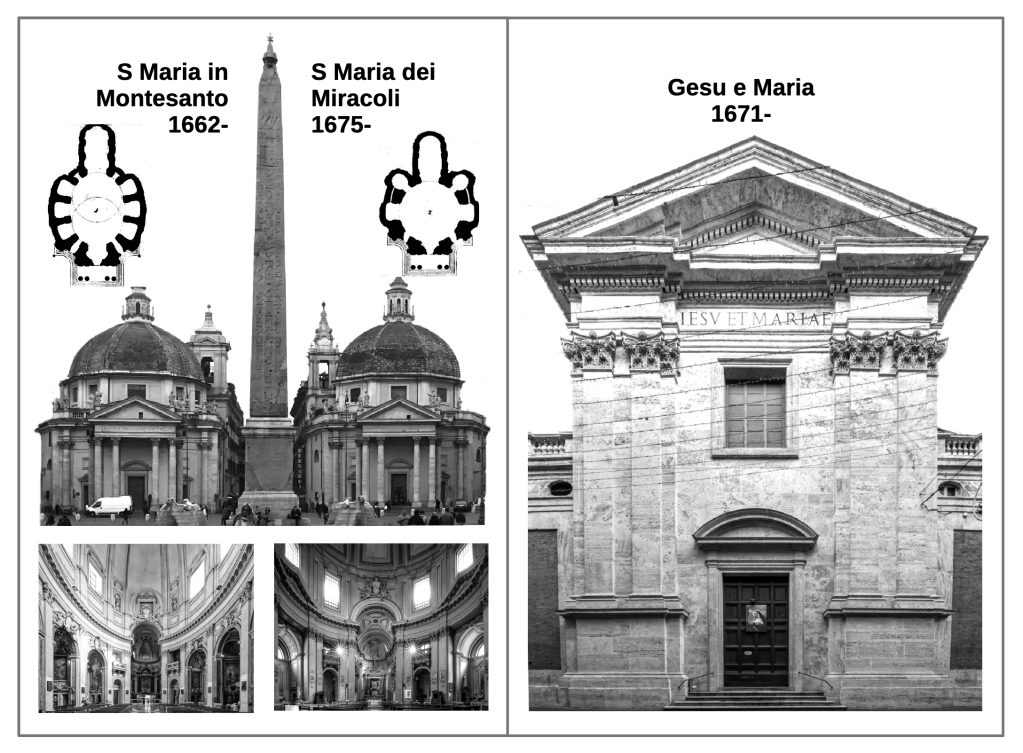

In 1662, Rainaldi designed two symmetrical churches to stand behind the obelisk in Piazza del Popolo. Because the surrounding streets prevented a perfect symmetry, Santa Maria in Montesanto was built on an oval plan and Santa Maria dei Miracoli on a circular plan, a strategy meant to disguise the differing site conditions. Rainaldi worked with Bernini and Carlo Fontana to complete the two churches. Bernini’s influence is visible in the classical temple fronts—the first true temple fronts built in Rome since antiquity. Because the papacy was facing financial difficulty during construction, plans for interior free-standing columns were replaced with pilasters.

The financial austerity of the later seventeenth century is also reflected in one of Rainaldi’s final façades, Gesù e Maria (1671– ). Its simplicity corresponds not only to economic constraints but also to broader stylistic shifts toward the more restrained classicism of the period. Just as Cortona’s later works abandoned Mannerist energy for calmer classical forms, Rainaldi’s later buildings display a similar move toward balance and simplicity. The idea of using a single large aedicule to frame an entire façade may have been inspired by Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (1670), which uses the same device.

Giovan Antonio de’ Rossi

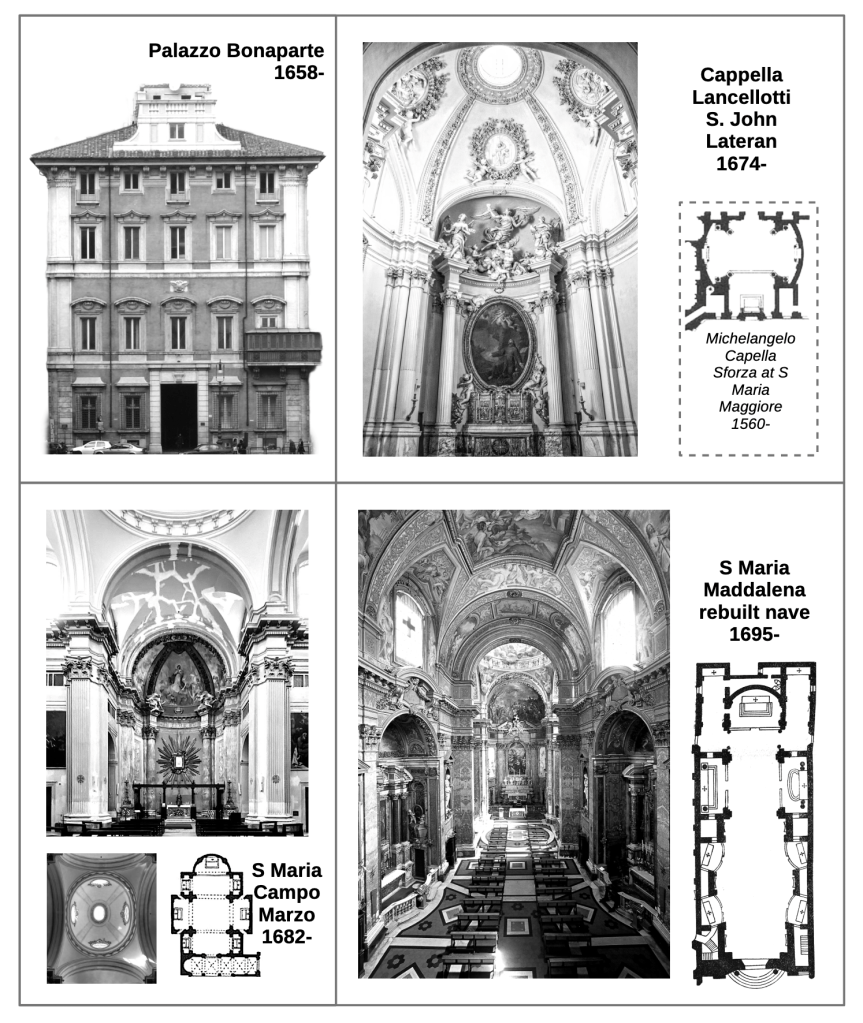

Giovan Antonio de’ Rossi’s Palazzo D’Aste–Bonaparte appears at first glance to be a typical conservative palace in the Farnese tradition. However, its sequence of gently curving window pediments gives the façade a lighter and more graceful character that anticipates the Rococo style of the eighteenth century.

De’ Rossi’s Cappella Lancellotti and Santa Maria in Campo Marzio belong more clearly to the High Baroque. The Cappella Lancellotti can be understood as a Baroque reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s Cappella Sforza (1560-), especially in its use of flattened transepts. Like Bernini’s San Tommaso (see figure 10), Santa Maria in Campo Marzio returns to the early Renaissance Greek-cross plan but places an oval dome above it. Instead of allowing the oval form to shape the interior walls, however, de’ Rossi maintains a strict rectilinear classicism below the dome.

In his remodeling of Santa Maria Maddalena, de’ Rossi experimented more boldly by designing an oval nave topped with a polygonal roof—an arrangement comparable to Rainaldi’s Santa Maria in Campitelli (see figure 13). But unlike Rainaldi, de’ Rossi did not extend the bulging nave with protruding side chapels. This results in a tightly integrated plan that anticipates the compact, unified church layouts of the eighteenth-century German Baroque (see Evolution of the Church Floorplan, Part 3, figure 8).

Carlo Fontana

Carlo Fontana has already appeared in connection with Rainaldi’s twin churches at Piazza del Popolo. In addition to that collaboration, he designed two notable façades in the late seventeenth century.

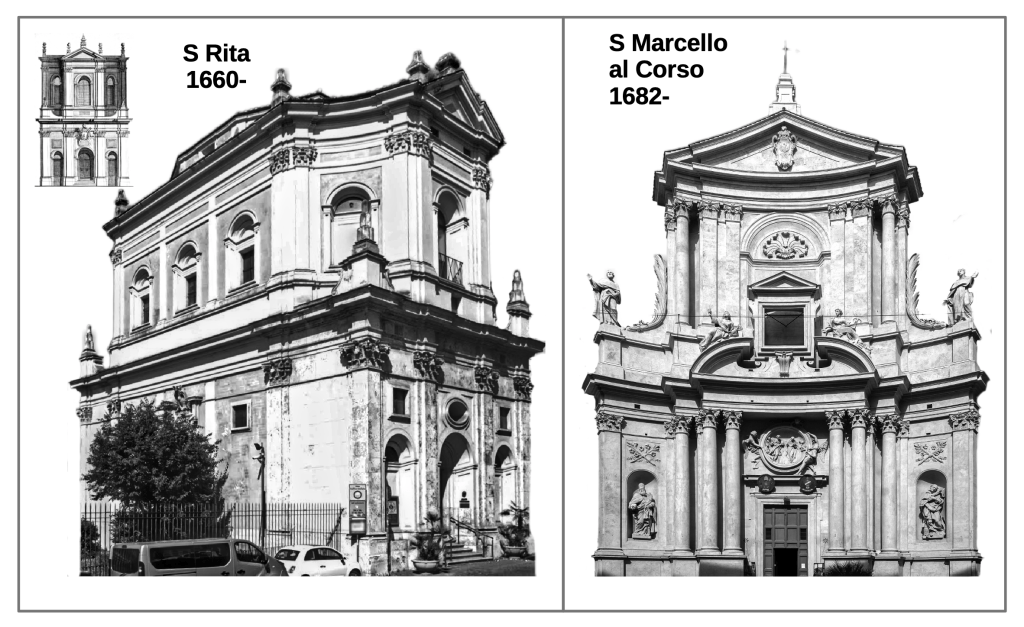

Santa Rita (1660– ) appears to have been modeled on Bernini’s façade for Santa Bibiana (see figure 10). Its arches are deeply recessed and slightly slanted to enhance the illusion of depth, echoing another Berninian device found on the upper story of Maderno’s Palazzo Barberini (see figure 5), which had been designed by Bernini. The concave side bays of the upper story wrap around the sides of the church—a practical choice given the narrow street frontage, allowing the façade to be better viewed from an oblique angle.

At San Marcello al Corso (1682– ), Fontana reintroduced free-standing columns at a time when most churches relied on simpler pedimented compositions due to limited budgets. Their use gives the façade a distinctly High Baroque character, even as most contemporary buildings were moving away from the more elaborate forms of earlier decades. The façade is gently concave, and Fontana reverses the arrangement of pilasters and columns between the lower and upper stories, producing a balanced and harmonious composition. This emphasis on balance reflects the growing classicism of the late seventeenth century, even as the building retains elements of earlier Baroque vocabulary.

Fontana also added a prominent central aedicule between the broken pediment—apparently intended to house a sculpture that was never executed. This aedicule stands in front of a window preserved from the earlier façade, resulting in an unusual but characteristic late-Baroque layering of forms.

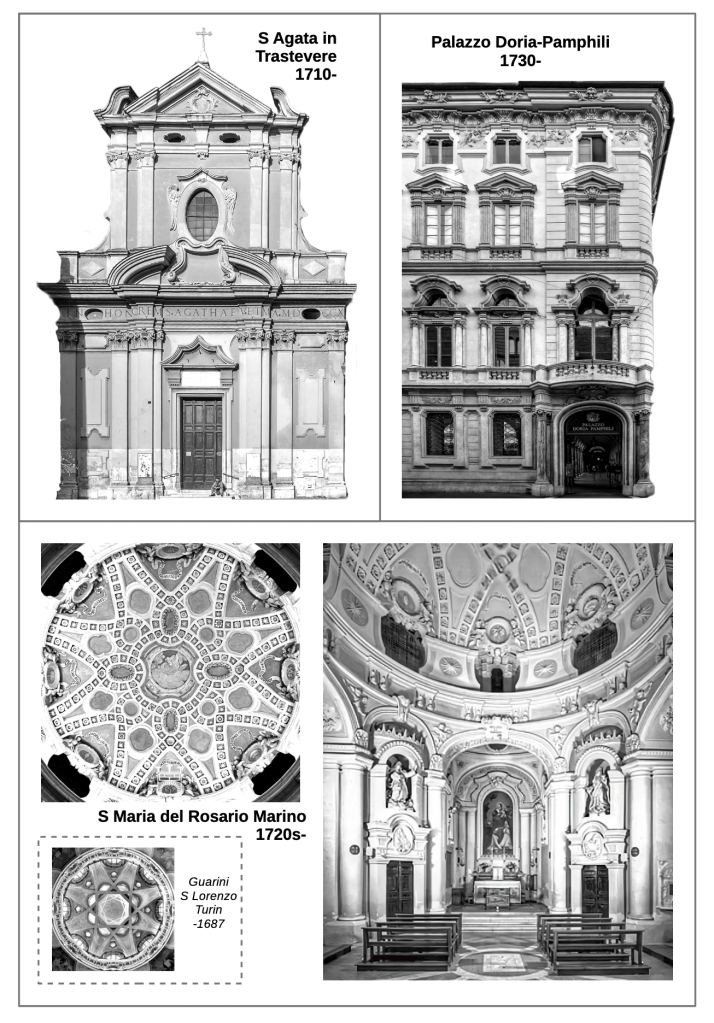

Rococo: Recalcati and Sarde

The Rococo style came to Rome with the façade of Sant’Agata in Trastevere (1710– ), designed by Giacomo Onorato Recalcati. It is a familiar Il Gesù type façade, but covered with ornamental motifs that bear little structural relationship to the underlying architecture. These decorations ultimately derive from the richly inventive vocabulary of Borromini, but they lack Borromini’s structural discipline and geometric rigor.

The nearby Rococo church of Santa Maria del Rosario (1720s) in Marino shows a different approach. Here, architect Giuseppe Sardi drew inspiration from both early Baroque ornament and Baroque structural techniques. The abundant stars and rosettes reflect the decorative vocabulary of Borromini, while the interlocking ribs and perforated vault of the dome recall the dome of Guarino Guarini’s San Lorenzo in Turin.

The Palazzo Doria-Pamphili (1730– ) provides another example of Rococo architects looking back to Borromini. In particular, the façade shows clear echoes of Borromini’s Collegio di Propaganda Fide, especially in the dramatically projecting window frames. Architect Gabriele Valvassori departed significantly from the conservative Farnese-type façade by enlarging and elaborating the window surrounds and reducing the amount of wall surface between them. This creates a far more energetic and restless façade than those of the High Baroque, marking a clear shift toward the livelier surfaces characteristic of the Rococo.

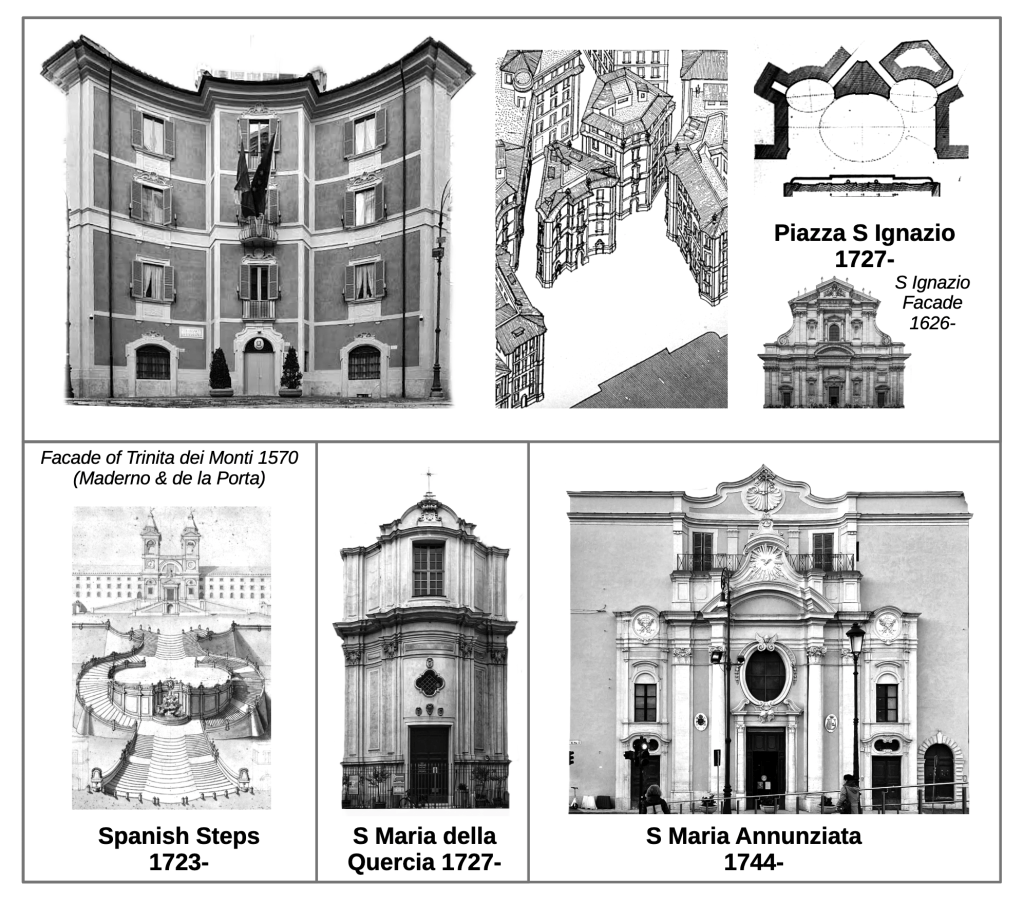

Rococo: Filippo Raguzzini and Others

The redesign of Piazza Sant’Ignazio in 1727 reflects the changing priorities of the Rococo period. The square had long been dominated by the large, early Baroque façade of Sant’Ignazio (1626– ), a traditional Il Gesù–type composition that by the eighteenth century appeared outdated. The architect Filippo Raguzzini transformed the entire piazza by adding a set of gently convex palazzi arranged to allow entrance from six different points. This curvilinear, stage-like setting shifts visual emphasis away from the church and toward the surrounding architecture—reversing the hierarchy seen at Santa Maria della Pace (see figure 12), where the palazzi were designed to direct attention toward the church façade.

Raguzzini’s façade for Santa Maria della Quercia (1727-) is equally unconventional. Although it adopts curving lines reminiscent of Borromini, the pilaster moldings are understated, and the main doorway and central window are left unadorned, without pediments or entablatures. The result is a strikingly modern reinterpretation of the traditional two-story church façade.

A similar Rococo spirit appears in Pietro Passalacqua’s small chapel of Santa Maria Annunziata (1744– ). Like Sant’Agata in Trastevere, it playfully reworks the Gesù façade type. Structurally, it is also unconventional. The facade is placed on top of a much wider wall surface. But on the lower level, the façade projects outward in front of the wall, while on the upper level it recedes behind the wall, creating a whimsical spatial effect.

One of the most ambitious urban projects of the early eighteenth century was the construction of the Spanish Steps (1723– ) by Francesco de Sanctis. Their overall arrangement recalls the monumental public works of the High Baroque—such as Bernini’s colonnade at St. Peter’s or the terraced gardens of Baroque palaces—yet the subtle curvature and fluid detailing of the steps reflect the lighter, more decorative spirit of the Rococo.

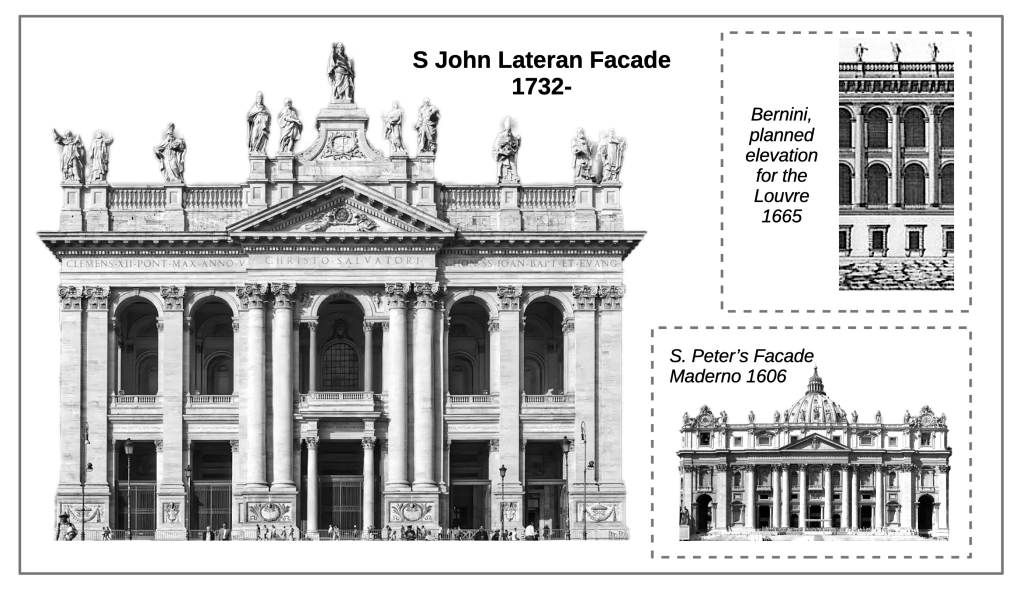

The Lateran Facade and the Return to Classicism

In 1732, a competition was held for a new façade for St. John Lateran. The winning design, submitted by Alessandro Galilei, was strikingly austere and classical—especially when compared with the Rococo-inspired proposals of his competitors. Galilei’s façade was criticized at the time for resembling the garden loggias of palace architecture, and it does show the influence of Bernini’s unrealized designs for the Louvre (1665). This criticism underscores a broader paradox of the Baroque era: the most exuberant and experimental forms were often reserved for churches, while palace architecture tended to remain more conservative and classical.

Galilei’s design also draws a deliberate connection to Maderno’s façade of St. Peter’s. Like St. Peter’s, the Lateran façade employs a giant order of columns, an attic with a balustrade and statuary, and a prominent temple pediment. The ground-floor loggia features subsidiary columns within each bay, a motif ultimately derived from Michelangelo’s Palazzo dei Conservatori (1563).

One of the façade’s most notable features is the exceptional height of the pedestals. Combined with the strong attic and entablature, they form a well-proportioned architectural frame. The result is a far more balanced composition than the unusually elongated façade at St. Peter’s.

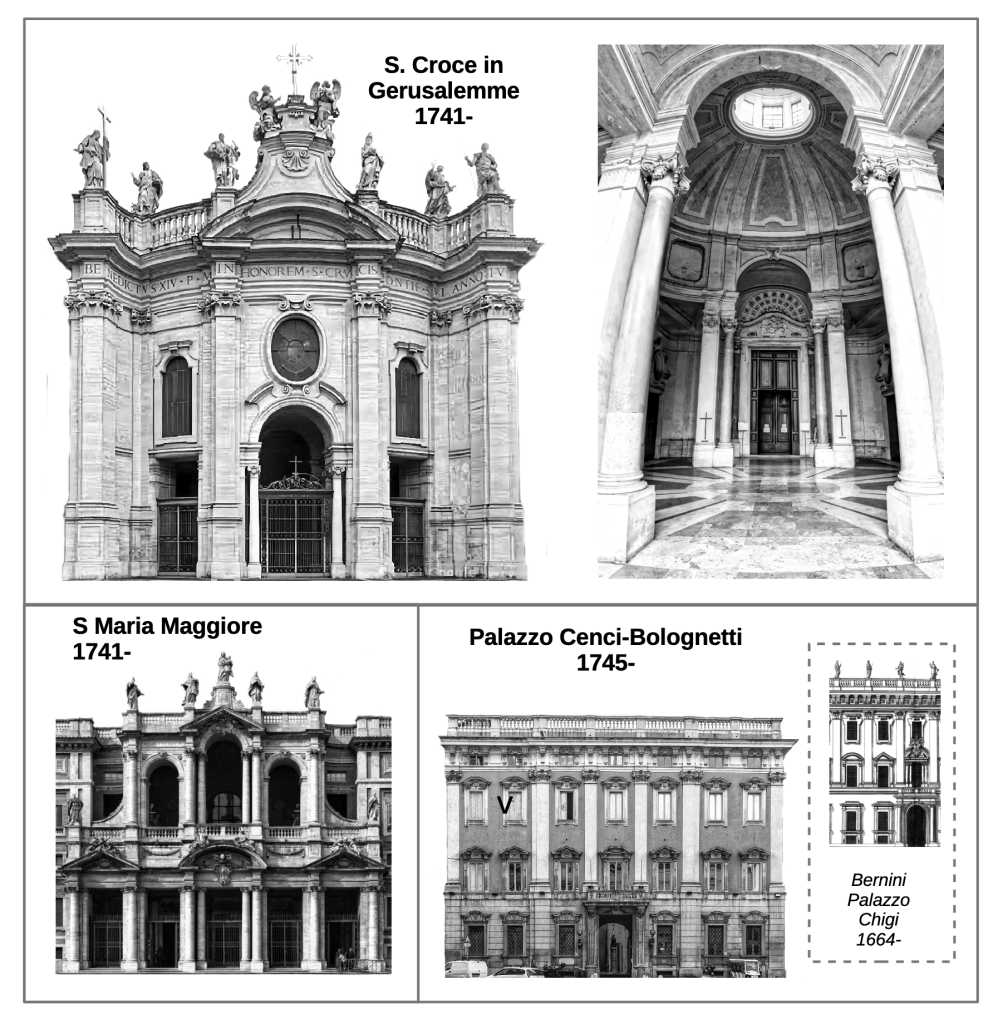

Later Rococo Classicism influenced by the Lateran Facade

After the completion of St. John Lateran, major church commissions in Rome adopted a new, austere sense of grandeur. The façade of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (1741– ) incorporates Baroque and Rococo touches—such as the oval window, the crown above the central pediment, and the gently curved façade—but like the Lateran, it is framed by large pediments with broad, open voids. The church also features a unique oval narthex.

At Santa Maria Maggiore, Ferdinando Fuga repeated the Lateran’s open two-story loggia, though he omitted the giant order and classical temple pediment. Instead, he retained the Il Gesu arrangement of three upper bays over five lower bays, which keeps the façade within the Baroque tradition. Fuga’s preference for restrained classicism is even more apparent in his Palazzo Cenci-Bolognetti (1745– ), whose design draws on the sober precedent of Bernini’s Palazzo Chigi (1664– ).

The End of the Baroque Age

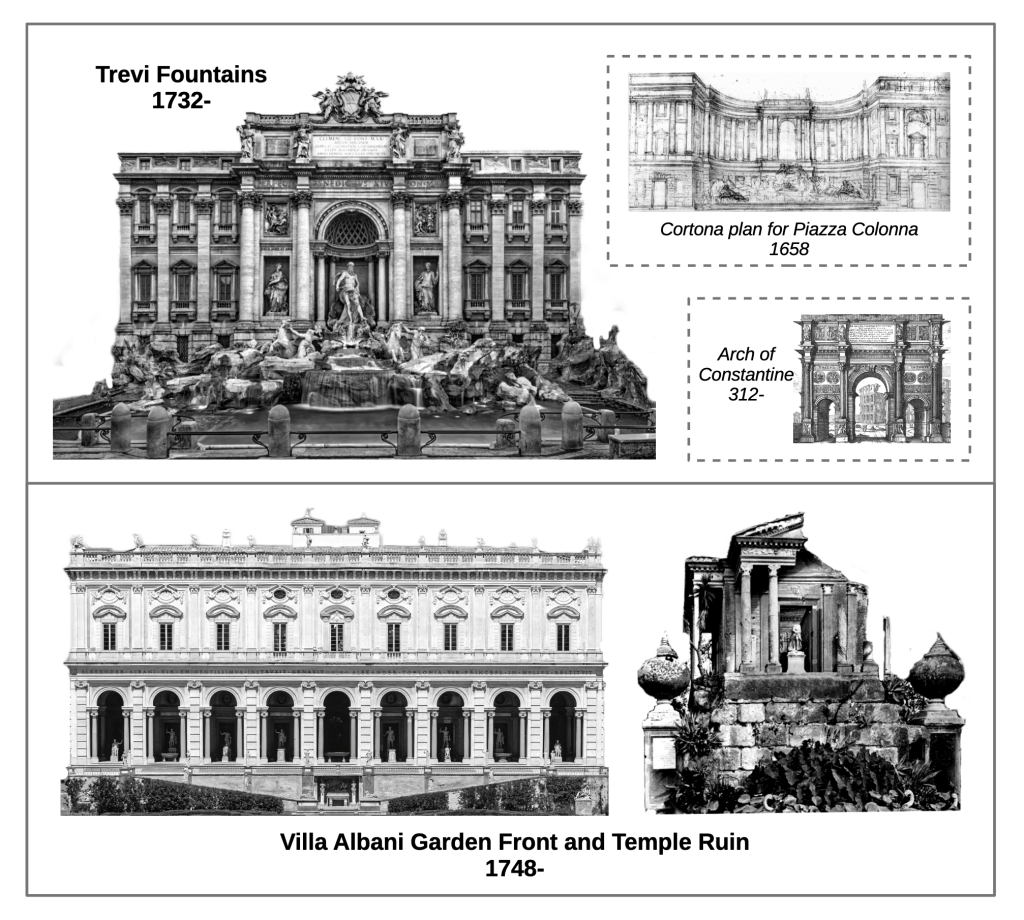

The Trevi Fountains (1732– ) are even further removed from traditional Baroque forms. Its architectural backdrop is closely modeled on the Arch of Constantine (312), a reference to Roman antiquity that anticipates later historicism. However, the overall design retains the theatrical scale and dramatic staging of Baroque architecture. Pietro da Cortona had drawn a similar fountain in his 1658 fountain design for Piazza Colonna. Nicola Salvi borrowed Cortona’s hierarchical layout while abandoning the Baroque preference for curving façades.

The last major Baroque architect in Rome was Carlo Marchionni. At the garden front of Villa Albani, Marchionni looked back to the Late Renaissance Mannerism, using strongly rusticated columns on the lower loggia. The upper story features aedicules and window surrounds treated in a more refined Rococo manner. Unlike Baroque architects, Marchionni deliberately avoided emphasizing the central bays, abandoning the hierarchical emphasis that defined Baroque façades. Instead, he adopted the neoclassical preference for repeated bays and evenly distributed proportions.

Villa Albani housed an important collection of ancient art curated by Johann Joachim Winckelmann, one of the founding figures of neoclassicism. Winckelmann collaborated with Marchionni on the design of three small garden temples at Villa Albain, including a faux Greek ruin. Although garden follies of this kind were common in eighteenth-century English landscapes, they were unusual in Italy. Their appearance in Rome signaled that the Baroque era was drawing to a close and that a new neoclassical age—grounded in archaeological study and admiration for ancient Greece—was beginning.

Leave a comment