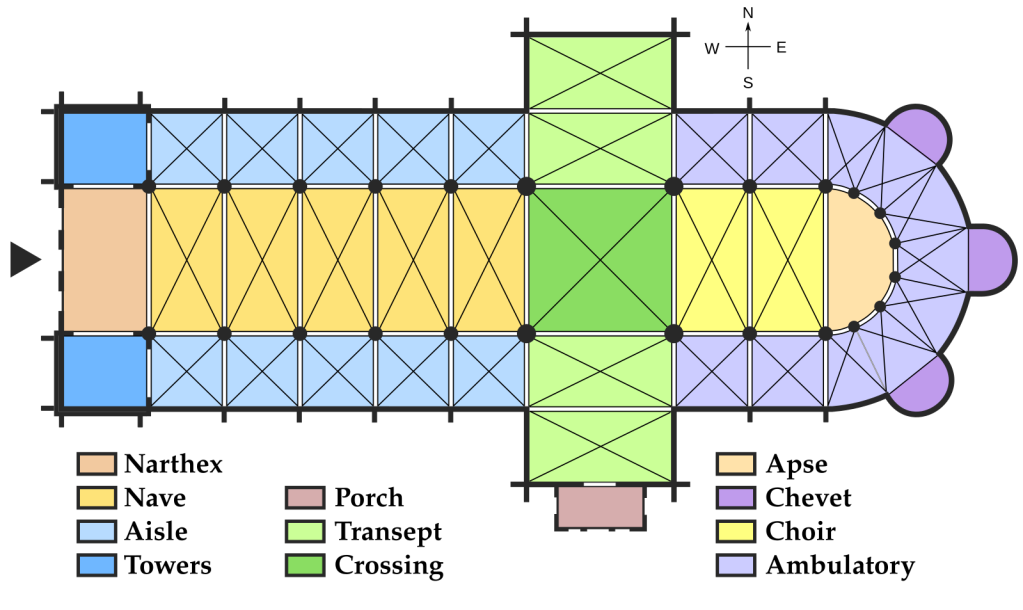

The archetypal cathedral is a cruciform structure oriented from west to east with a towered west entrance (narthex) and a rounded east end (apse). This formal structure has its origins in the ancient Roman basilica.

Early Christians opted to worship in Roman basilicas rather than Roman temples in part because basilicas were secular structures unassociated with paganism. With their wooden roofs, they were also cheaper to build. Banks of clerestory windows ensured that the structures were filled with light, an important symbol for Christians. The rectangular orientation of basilicas was also well suited to the processionals associated with Christian worship.

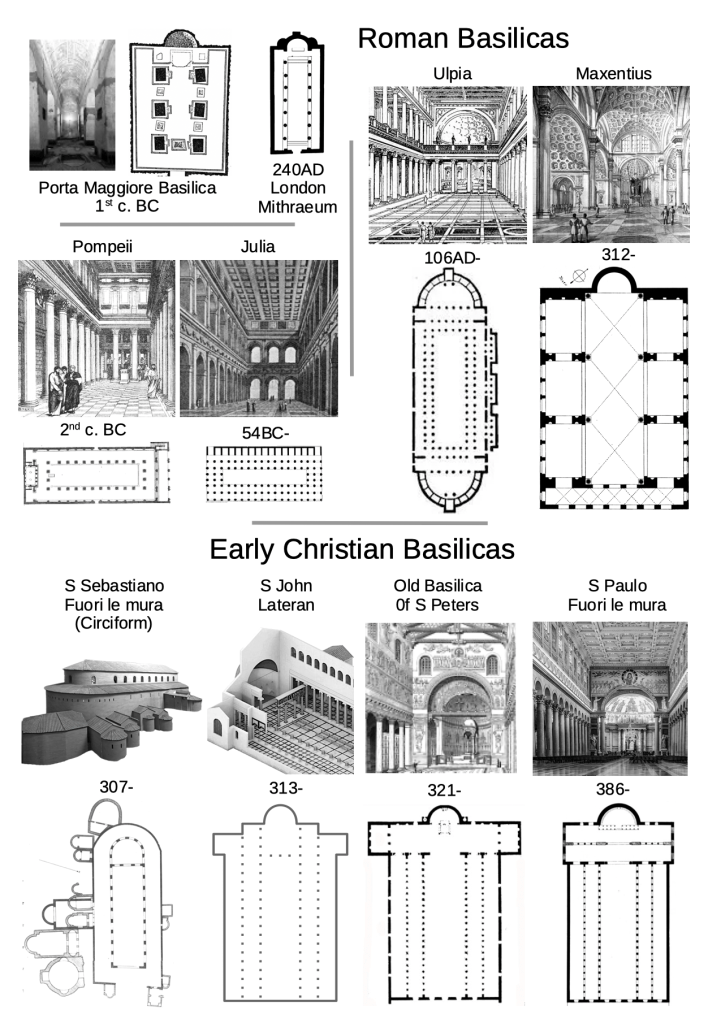

The prototypical Roman basilica was a rectangular shed with an inner colonnade, a high central nave, and a bank of clerestory windows (see Pompeii 2nd c. BC). Julius Caesar’s double aisled Basilica Julia had two banks of clerestory wwindows. In 106AD, Basilica Ulpia repeated the double aisled format of Julia and added two massive apses on both ends. Basilica Maxentius (312-) utilized a smaller apse at one end, sometimes called an exedra. This basilica was also notable for the massive stone vault over its nave, which would prove to be an inspiration to architects of stone vaulted churches in later centuries (most other basilicas had wooden roofs). Underground mini-basilicas were also built for mystery cults such as Porta Maggiore (1st c. BC) and the London Mithraeum (2nd c. AD).

There were two basic kinds of early Christian rituals: funerary celebrations and eucharistic masses. One of the first Christian basilicas ever built, S. Sebastiano Fuori le Mura (307-), was associated with funerary celebrations. It is sometimes called a “circiform” basilica, because its aisles wrapped around the structure, similar to a Roman circus built for chariot racing. Its rounded aisle contained tombs and smaller mausoleums attached to it. Visitors could walk through the aisle around the entire length of the basilica, making it the first ambulatory.

The first major basilica built for the Christian eucharist was S. John Lateran (313). Reproductions of the original structure, like the one done by historians at Cambridge University (shown above), show waist-high structural barriers delineating pathways along the nave (called solea or schola), and a colonnade separating the altar from the nave (called a fastigium). Solea disappeared from the ritual structure of christian worship, but fastigium can be seen into the middle ages (for example, S Miguel de Escalada 913).1 A structure similar to the fastigium can be seen at Basilica Ulpia centuries earlier, where the peripteral colonnade cuts off direct access to the apse. S. John Lateran also contained a “proto-transept” consisting of spaces attached to the altar area and set apart with colonnades. No one knows exactly what function this transept might have served.

The first proper transept was built at S. Peter’s Basilica (321-), where it served as a space for the masses to worship at the shrine of S. Peter who was buried in a crypt directly underneath. S. Peter’s was originally a funerary basilica like S. Sebastian. Over time, the figure of S. Peter became associated with the central authority of the church in Rome, so the basilica took on much greater importance, eventually becoming the mother church of all Christendom. Later medieval basilicas included S. Peter-style transepts to emphasize their allegiance to the church in Rome (figure 3). The transept also gave the church a cruciform structure, a symbolic aspect that may or may not have been intended by the architects who designed the original S. Peter’s.

Unfortunately, all three of these early Christian basilicas have been lost. S. Paulo Fuori le Mura (386-) is the closest we can get to experiencing a great 4th century Christian church. Although it was destroyed in a fire in 1832, S. Paulo was rebuilt according to its original double-aisled floor plan. The archway framing the apse at S Paulo resembles a triumphal arch, a practice that would be carried on in later centuries.

Late Antiquity into the Dark Ages

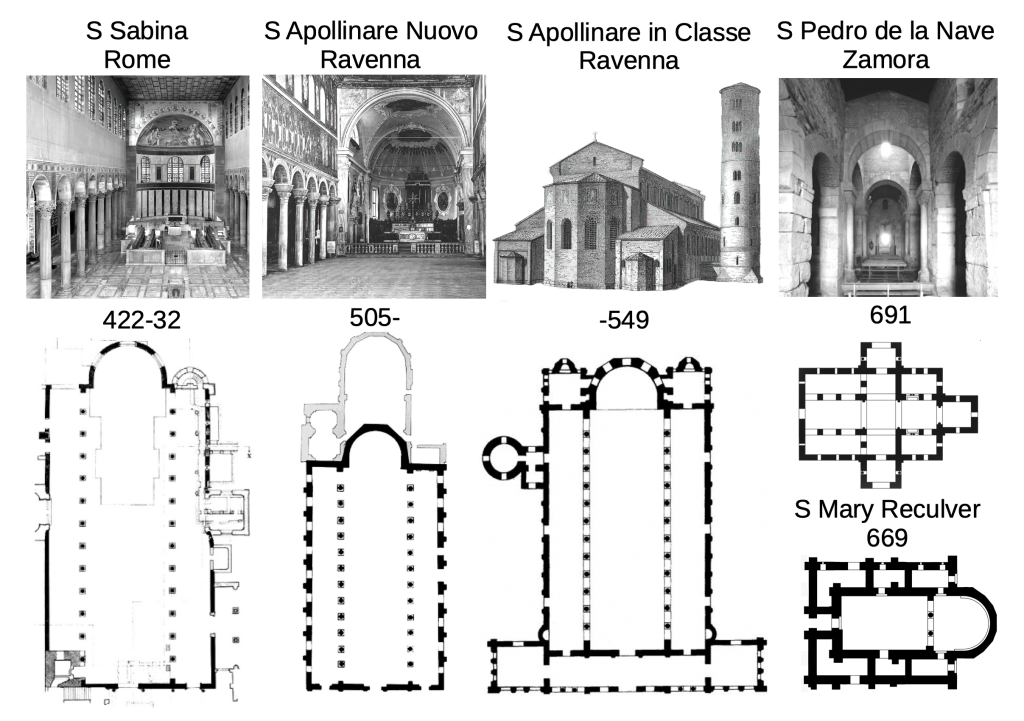

S. Sabina, built during the early 5th century, still retains much of its original appearance. It even contains a conjectural solea, designed in 1936 as an attempt to reimagine the lost ritual traditions associated with it.

In the late 5th century, the western half of the Roman empire collapsed, causing a catastrophic decline in urban life and architecture. Power gravitated to barbarian tribes outside of Rome, notably the Ostrogothic kingdom based in the city of Ravenna. This city contains two important basilicas, both built in the single-aisled format of S. Sabina. They are celebrated for their stunning mosaics and sophisticated sculptural ornamentation.

Elsewhere in Europe, small rural congregations replaced large urban ones. A notable miniature basilica survives from Visigothic Spain – S. Pedro de la Nave. It features a nave, aisles, transept, and a square apse. Unlike earlier basilicas, the various sections of S. Pedro are separated from each other by large piers, walls, and narrow passageways.2 Similar delineations can be seen in the 7th century Anglo-Saxon floor plan at Reculver in Kent, England, which still exists as a ruin.3

The Carolingian Renaissance

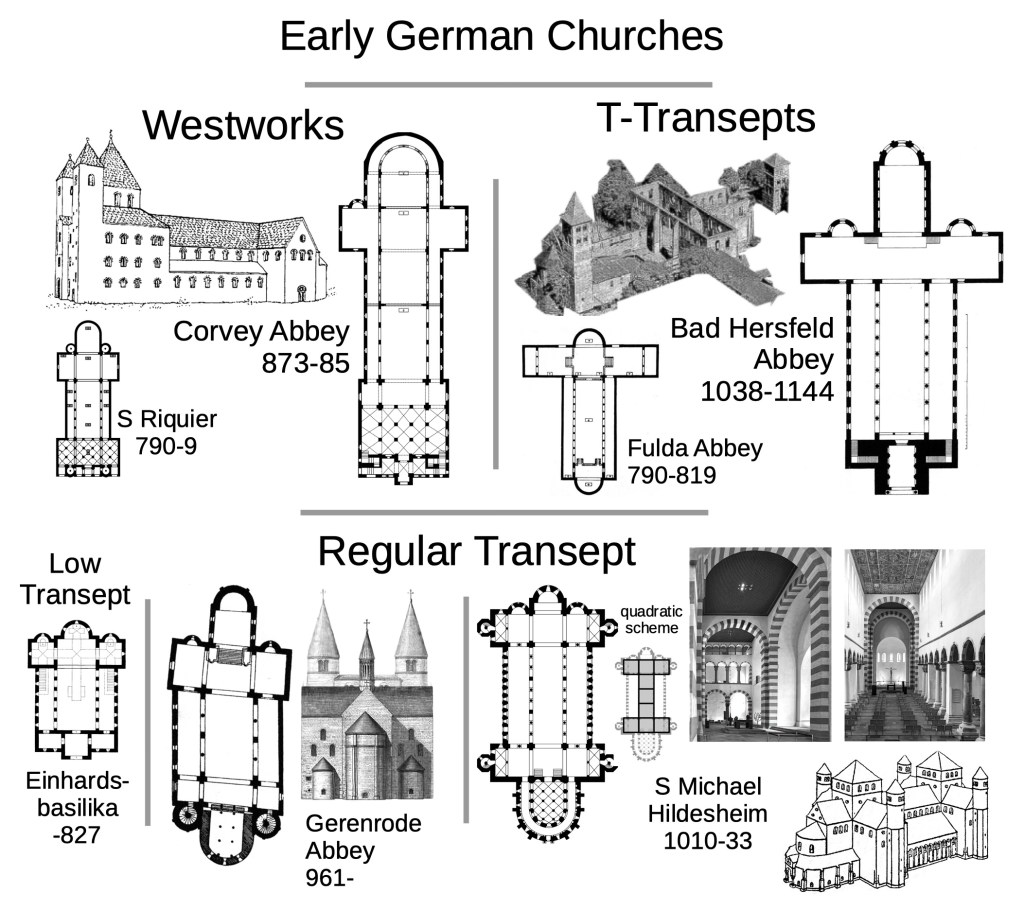

The conquests of Charlemange (748-814) brought greater stability to Europe and increased church patronage. Monasteries expanded in size and opulence. This period is often called “early Romanesque” because architects used ancient Roman building techniques and styles in Roman-like ways. But Carolingian architects also created structures that departed significantly Roman precedents.

Westworks were an important innovation (which I cover more extensively in Evolution of the Church Facade). The floor plans for S. Riquier and Corvey demonstrate that westworks were more than simple facades. They comprised a significant portion of the overall church floor plan (the westwork is the square portion of the building opposite the rounded apse).

Transepts were also regularized during this period. They can be classified in three types. T-transepts, seen at Fulda (demolished) and Bad Hersfeld (now a ruin), are patterned after the long transept at S. Peter’s basilica. Low transepts, like the one at Einhardsbasilika, are separate rooms with ceilings lower than the nave. Their floor plans resemble the rudimentary structures built during the dark ages (fig. 2).

The “regular transept” is the third type of transept dating from this period. A transept is said to be regular when it extends out from a square crossing.4 (A crossing is the area of intersection between the transept and the nave vessel). In a square crossing, each of the four sides contain archways of equal size. Gerenrode Abbey was an imperfect attempt to build a regular transept, but S. Michael’s Hildesheim represents the ideal. Renowned for its structural harmony, S. Michael is designed around a series of squares. In the nave vessel, three squares are articulated by sets of large alternating piers. The three-square pattern is repeated in the transept as well as the westwork. S. Michael also contains a square tower over its crossing, a device popularized during the Carolingian period.5

At their eastern ends, each of the churches in figure 3 contain a large apse flanked by two smaller apses (apart from Corvey Abbey with its single apse). When multiple apses all face the same direction they are said to be “in echelon.” Fulda, Gerenrode, and S. Michael also contain apses on their west ends, a variation found in many German churches during this period.

Cluniac Romanesque

During the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Viking raiders wrecked havoc on the European continent, setting back the progress attained under Charlemagne. The exception was Burgundy, where the great warlord Richard the Justiciar successfully repelled Viking incursions. Embattled monastic communities flocked to Burgundy. At the same time, the church in Rome was mired in scandal (the so-called “rule of harlots”). This meant that patronage shifted from Rome to the monasteries in Burgundy, most notably, the Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910.

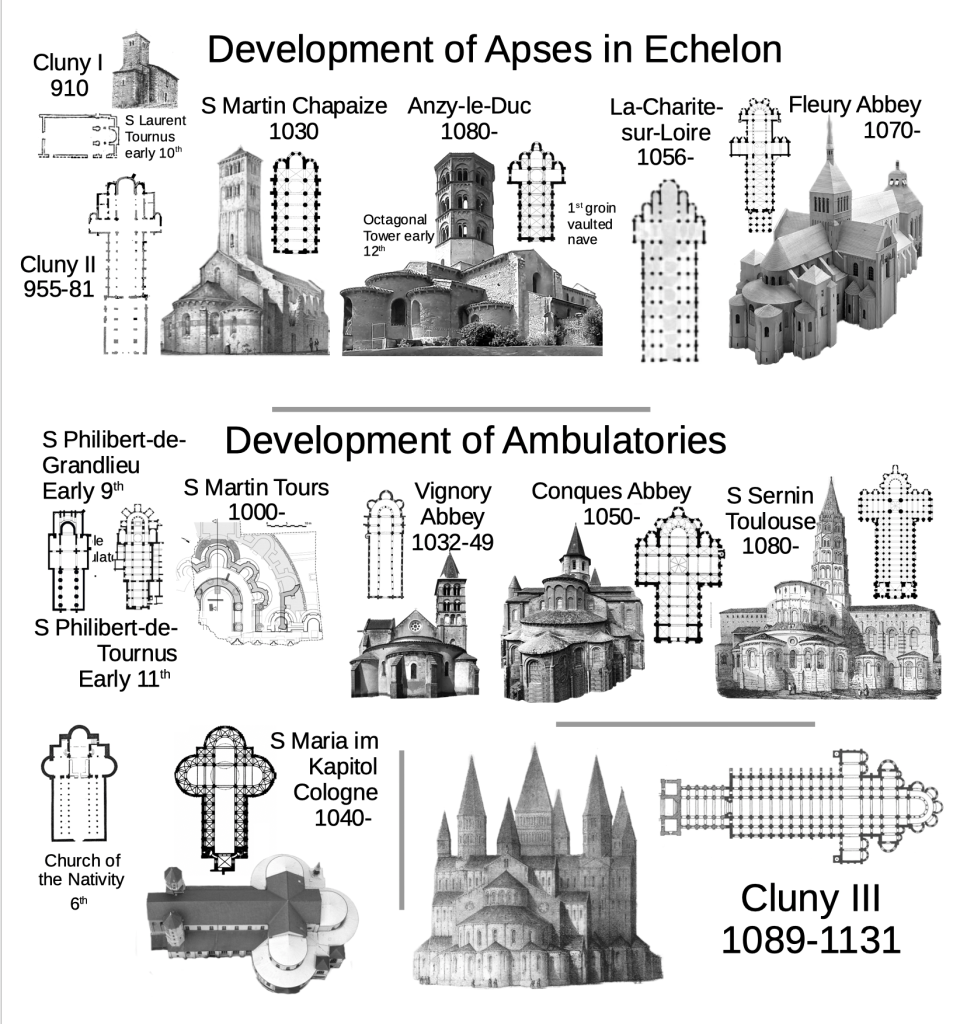

The abbey’s first church (Cluny I) was a small, aisle-less structure with a single apse. It probably looked much like the surviving S. Laurent chapel in Tournus, also built in the early 10th century. A few decades later, the Cluniacs began constructing an ambitious new church (Cluny II) with seven apses in echelon and the first barrel vaulted nave.

Cluny II no longer exists, but we can get a sense of what it looked like by examining some of the extant churches inspired by Cluny II. S. Martin Chapaize (1032-) is a less ambitious version of Cluny II with three chapels in echelon, Anzy-le-Duc (1080-) has five chapels in echelon. It also contains an octagonal tower added in the 12th century, which was to become a popular Burgundian Romanesque motif.

Like Cluny II, Cluny III (1089-) was destroyed in the French Revolution. However, we can study the precedents that inspired its grand design. This includes La-Charite-sur-Loire (1056-), one of the first double aisled basilicas to be constructed since the 4th century (fig. 1).6 It was built under the direction of the powerful Abbot Hugo who would go on to design Cluny III. Hugo was also involved in the design of Flury Abbey (1070-) which contains the first double transept, an innovation also adopted at Cluny III. With a double-aisled and a double-transepted church under his belt, Hugo was ready to embark on Cluny III in 1089.

Cluny III featured an ambulatory with radial chapels. This ambulatory allowed pilgrims to visit shrines and reliquaries in the chapels without disturbing the masses taking place in the choir throughout the day. Ambulatories were rare before the 11th century. An early square ambulatory survives at the 9th century abbey of S. Philibert-de-Grandlieu. S. Philbert-de-Tournous (early 11th) contains the first surviving ambulatory with square radial chapels. The first proper ambulatory with rounded apses was built at S. Martin in Tours circa 1000. It was enormously influential given the importance of the cult of S. Martin. In the 13th century S. Martin was expanded to include a double ambulatory, making it one of the great pilgrimage churches of the age. (Unfortunately it was also destroyed in the French Revolution.)

One of the earliest surviving ambulatories with circular radial apses is found at Vignory Abbey (1032-), albeit without transepts. In 1050, Conques Abbey was built on the S. Martin model. Conques was located along the popular pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. Its aisles formed a continuous route along the nave, around the transept, and into the ambulatory, facilitating the visits of vast numbers of pilgrims. S. Sernin Toulouse, also built along the pilgrimage route to Santiago, is an even larger version of Conques, with two additional chapels as well as a double aisled nave.7

S. Maria im Kapitol Cologne (1040-) features a particularly unique ambulatory. It wraps seamlessly around both the transepts and the choir, as at Conques. But at S. Maria, the transepts are rounded, creating a trefoil design. This was likely inspired by the 6th century Church of the Nativity in Jerusalem which also had rounded transepts.

French Gothic Consolidation

During the French Early and High Gothic periods, the sprawling Romanesque layouts exemplified by Cluny III were consolidated into compact floor plans. Transept lengths were reduced and moved to the center of the church. Nave widths were expanded and protruding apses were brought more closely into the arc of the choir, creating unified interiors.

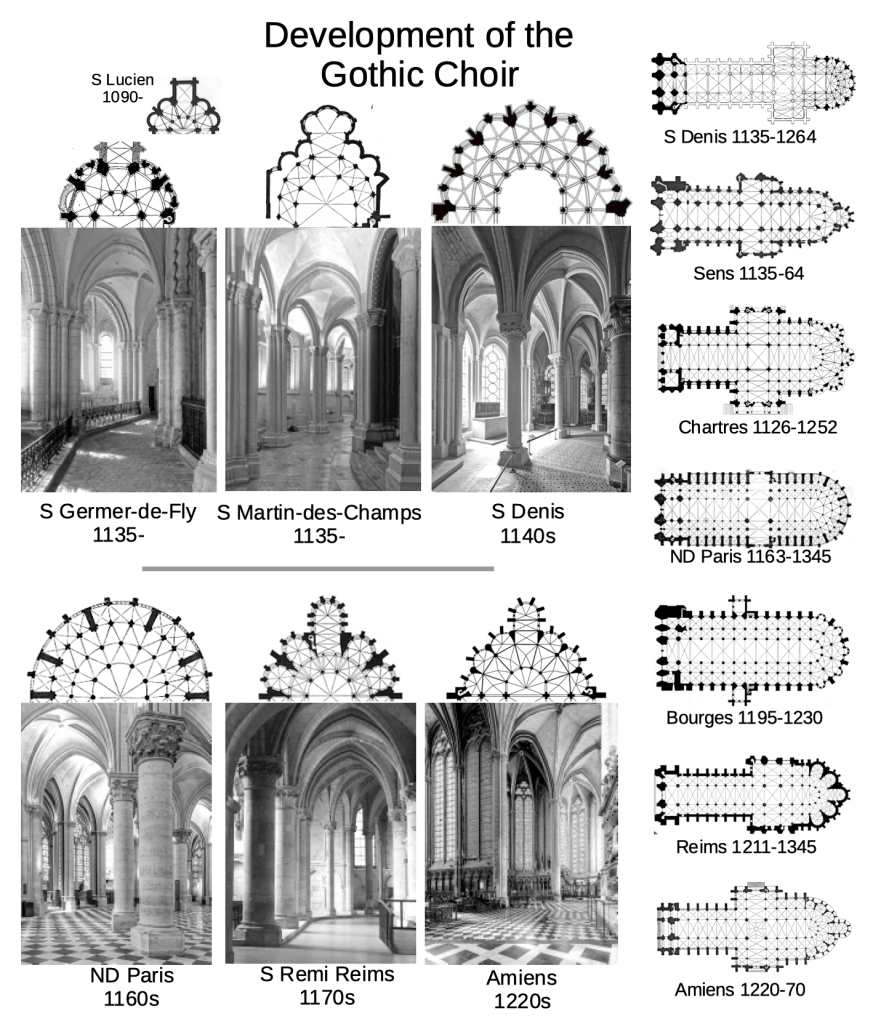

The process of consolidating apses into the choir began at the Romanesque church of S. Lucien (1090-), which had short apses protruding out of each bay of the choir, rather than more pronounced apses protruding from alternating bays, which had been the traditional Romanesque layout for radial apses. S. Lucien was destroyed in the French Revolution, but the surviving S. Germer-de-Fly (1135-) was built on a similar scheme.

The choir at S. Martin-des-Champs (1135-) also has apses protruding from each bay. However, there is a gap between the outer piers and the apses, which reduces the sense that the apse is a separate space. Rather than a set of radial chapels, we have the beginnings of a double ambulatory. Additionally, each apse has two large windows, bringing in light and further unifying the space. This scheme was perfected at S. Denis (1140-), widely considered to be the first gothic building. The columns articulating the double ambulatory are thin, enhancing the feeling of openness already being promoted by the double-windowed apses.

Notre Dame Paris is built on a similar scheme, but eliminates the apses entirely, creating an even more expansive sense of space that could almost be read as a triple ambulatory. S. Remi Reims takes the opposite approach. It articulates each individual apse with walls projecting diagonally toward the choir, cutting off what would have been the outer aisle of a double ambulatory. This particular scheme was repeated many times, including at the cathedral of Amiens, albeit with walls that were much thinner and lined with delicate tracery.

These gothic choirs clearly derive from the romanesque precedent of radial chapels built at pilgrimage churches. However, by bringing the apses within the arc of the choir, thinning the walls, and expanding the window area, gothic architects created unified interiors filled with light. For medieval pilgrims accustomed to dark, labyrinthine interiors, the effect must have been revelatory.

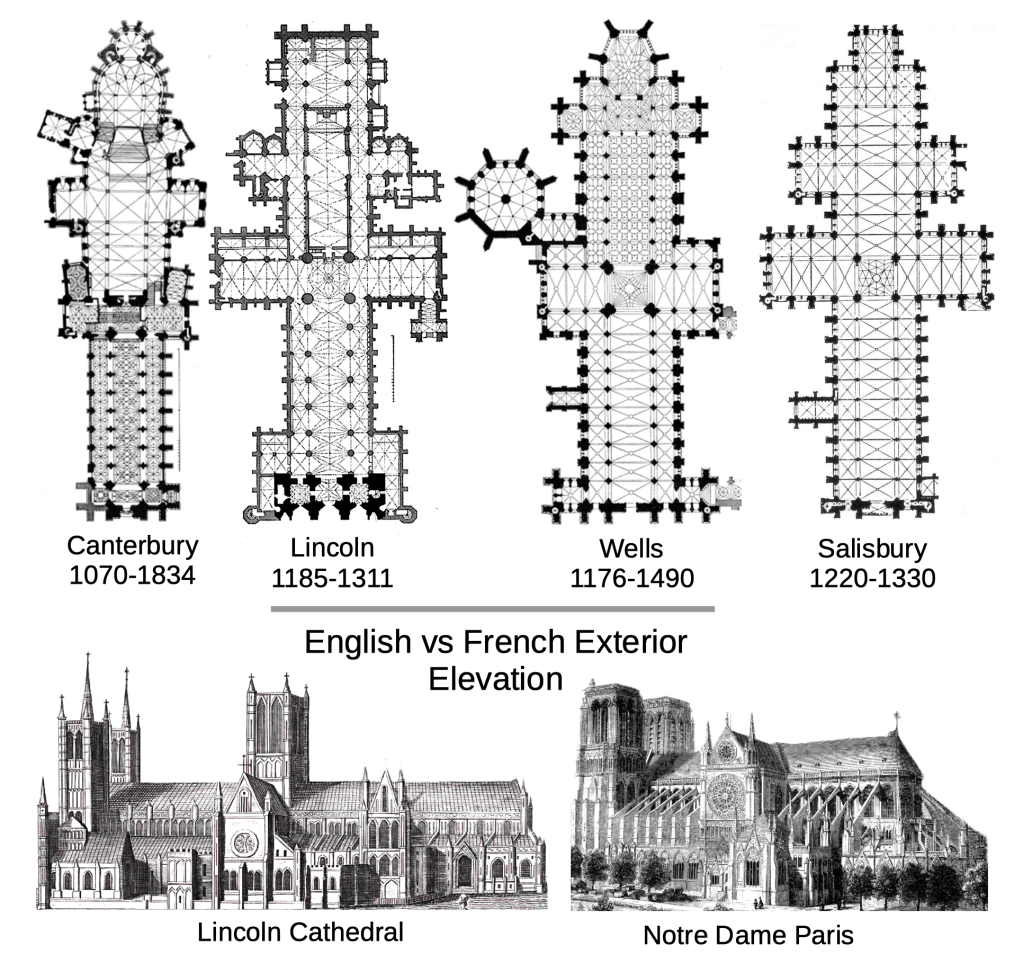

English Gothic Floor Plans

English Gothic cathedrals remained wedded to the compartmentalized character of earlier Romanesque floor plans. They preferred lower elevations with minimal flying buttresses and Cluny-style double transepts. Some of this was due to the fact that English Gothic Cathedrals kept the dimensions of the previous structures they were built to replace. But even entirely new gothic structures such as Salisbury Cathedral were built using the old Romanesque-style floor plans. English cathedral planners were also happy to add new additions without regard to the unity of structure as a whole. This is best exemplified in the disjointed floor plan at Canterbury Cathedral. All of this gave English gothic cathedrals a much different character than French gothic cathedrals. A cursory comparison between the exterior of Lincoln Cathedral and that of Notre Dame bears this out. Where Notre Dame is compact and uniform in its height, Lincoln is spread out and compartmentalized.

Later Gothic Floor Plans

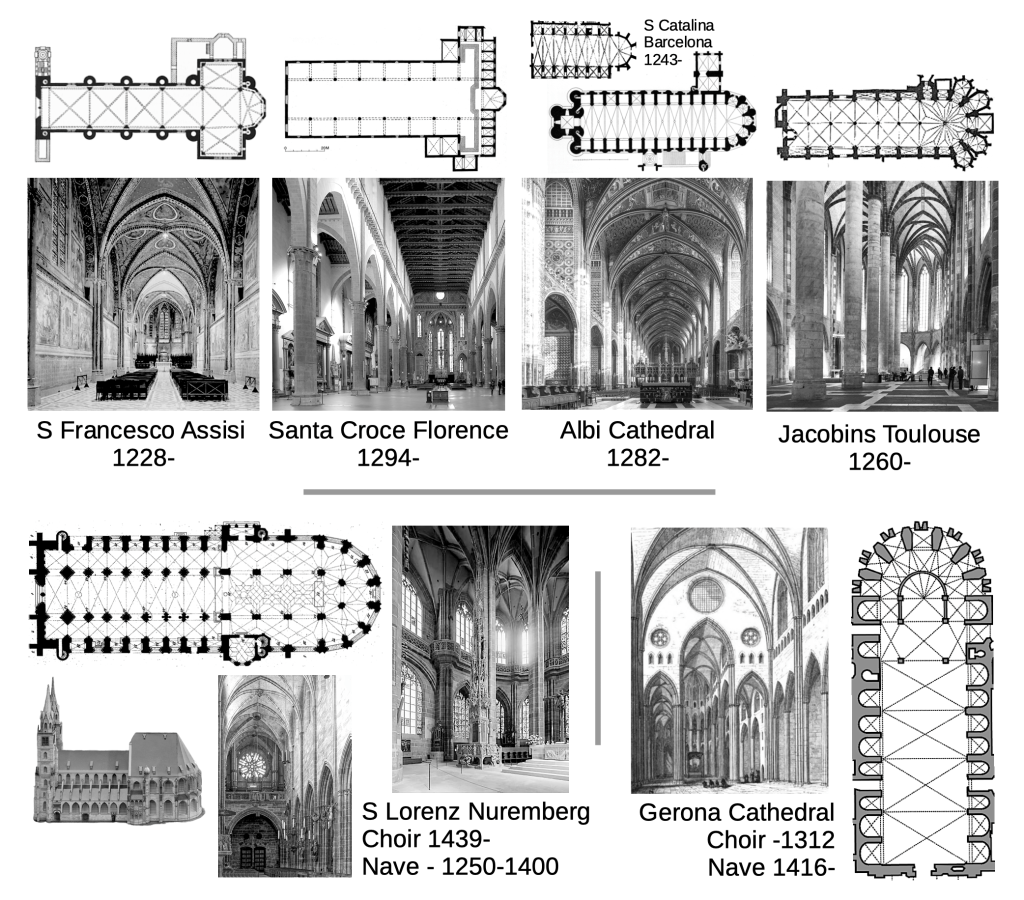

The era of High Gothic French cathedrals began to wane by the end of the 13th century. Popular new mendicant orders like the Dominicans and Franciscans emphasized simpler, more functional church plans designed for preaching to large congregations. Churches like S. Francesco in Assisi (1228-) featured broad, open naves without aisles which helped keep the focus on the preacher. When aisles were included, as at S. Croce in Florence (1294-), they were built with tall, wide arcades that lacked clerestories, creating a unified interior space.

The Dominican convent of S. Catalina in Barcelona (1243-) replaced the usual aisles with a series of separate chapels. This innovation was widely adopted in Spain and even influenced Southern France, where it can be seen at Albi Cathedral (1282-) and the Couvent des Jacobins in Toulouse (1260-). The church in Toulouse featured a particularly unconventional design choice: a colonnade running down the center of the nave.

Simplified, mendicant-style floor plans became increasingly common throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, reflecting the Late Gothic emphasis on spatial unity. S Lorenz Nuremberg, built in two separate stages, exemplifies this shift. Its nave was started in 1250 and includes a clerestory with separate, lower aisles typical of the High Gothic period. The choir, started in 1439 during the Late Gothic period, abandons the clerestory, making the aisles and nave the same height. It also widens the arcades and simplifies the columns, which rise seamlessly from the ground, branching into the high vaults like trees. These columns have no horizontal bands or capitals, which creates a greater sense of verticality and enhances the organic sense of unity from floor to ceiling.

Gerona Cathedral also illustrates Late Gothic trends, but in the opposite direction. Its choir, completed in 1312, adheres to earlier High Gothic traditions: an aisled ambulatory with radial chapels. The nave, begun in 1416, abruptly discontinues the aisles from the choir, creating a large aisle-less nave. It was a radical choice to make, for the resulting nave became the widest in all of Gothic architecture. Its remarkable width was further augmented by a series of chapels flanking the nave, a remnant of the design innovation first noted at S. Catalina .

Part 2 traces the evolution of centralized floor plans deriving from Roman mausoleums and Christian baptistries. Renaissance and Baroque architects adopted centralized schemes, often combining them with rectangular basilican formats. Since then, church architects have routinely utilized both basilican and central plans, or a combination of both.

- A notable solea can be seen at the Basilica of S. Clemente in Rome (1108-23) ↩︎

- San Juan de Banos (Palencia) c. 611 is another notable Visigothic survivor ↩︎

- S. Lawrence in Bradford-on-Avon is the best preserved Anglo-Saxon chapel in England. However it contains a much simpler floor plan than the ruin at Reculver. ↩︎

- The one of the earliest regular transepts is Seligenstadt Basilica (830-), which was modeled partially on the unbuilt S. Gallen Monastery Plan (820), an idealized layout based on a quadratic scheme, but only perfected at S. Michael Hildesheim (1010). See also Justinuskirche Höchst (830-) ↩︎

- One of the earliest crossing towers is the Carolingian Oratory of Germany-des-Pres (803-), built not on a basilica plan, but a central Greek cross plan. ↩︎

- The double aisles of La-Charite-sur-Loire were consolidated into a single aisle in later centuries. Only the 11th century transepts have been retained. ↩︎

- Along with Conques and Toulouse, Santiago de Compostela is the third great pilgrimage church. It was built starting in 1075 and features a similar floor plan to Toulouse, albeit without the double aisled nave. ↩︎

Leave a reply to NateBergin Cancel reply