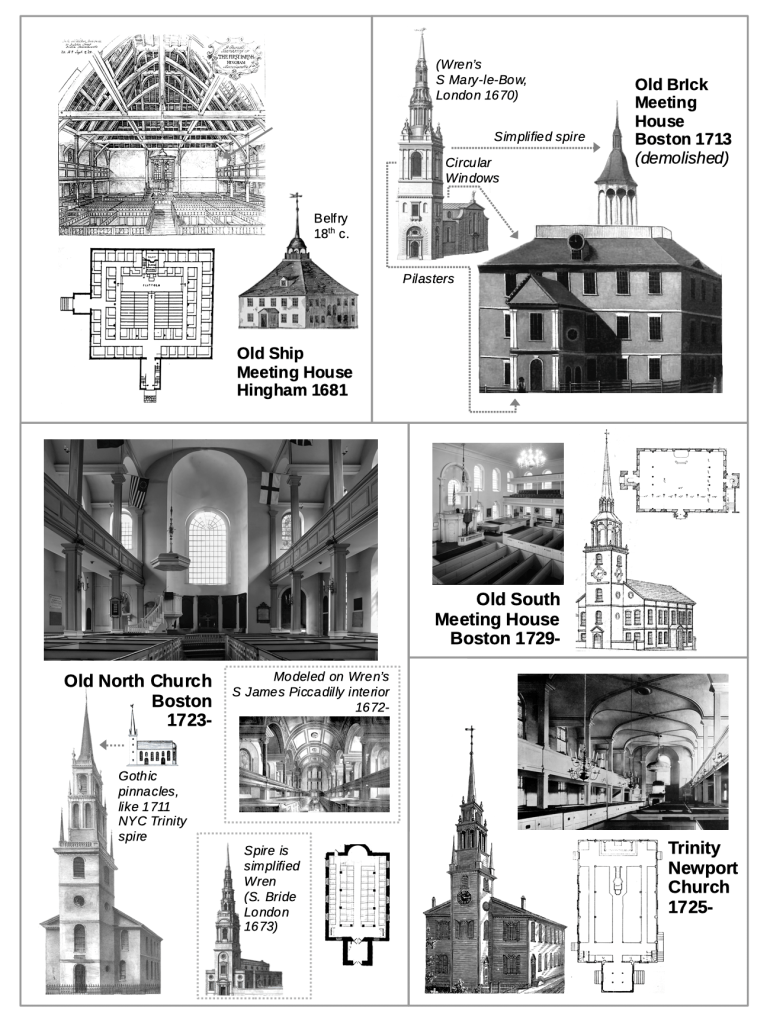

The puritans of New England rejected any architectural motifs that might have Catholic or Anglican associations, including naves, altars, and steeples. They even rejected the word “church,” opting to worship in what they called “meeting houses.” The oldest surviving meeting house in New England is Old Ship Meeting House in Hingham, MA, built in 1681. It was constructed on a square two story plan topped with a hipped roof. Inside, galleries flanked three of its sides with a pulpit at the center of the fourth side. In the 18th century a steeple was added, reflecting the shift away from the 17th century’s iconoclastic puritanism toward the more theologically moderate congregationalism of the 18th century.

Classical architectural details started emerging in New England in the early 18th century. Boston’s Old Brick Meetinghouse, built in 1730, included superimposed classical pilasters, small circular windows, and a simple octagonal spire. These details were inspired by the classical architecture of Christopher Wren, who had built 51 churches in and around London after the great fire of 1666.

An Anglican congregation reintroduced the traditional rectangular church format at Boston’s Old North Church in 1723. It looks like a simplified version of Wren’s S. Bride Church of 1673 with its tall, tiered spire. Old North also contained gothic pinnacles surrounding its spire, a feature seen in the spire of a now lost predecessor to Holy Trinity in New York City, built in 1711. The interior of Old North was modeled closely on Wren’s S. James Piccadilly of 1672, with a barrel vaulted nave and transverse vaults between the piers.

Two years after construction on Old North began, an Anglican congregation in Newport built Trinity Church. It was closely modeled on Old North, but built in wood rather than stone. Its spire was even more elaborate than Old North’s. The interior also adhered to Old North’s model, but substituted the barrel vaulted nave for a shallow groin-vault.

In 1729, Congregationalists in Boston built Old South Meeting House. It kept the traditional New England meeting house plan, but added a large spire onto one of its sides. The result was a towered entrance opening onto an interior with pews facing the left-side wall where the pulpit was placed, rather than having the pulpit opposite the towered entrance. Hybrid plans combing spires with meeting houses were used by non-Anglican protestant denominations throughout the 18th century before gradually falling out of use in the 19th.

The Influence of James Gibbs

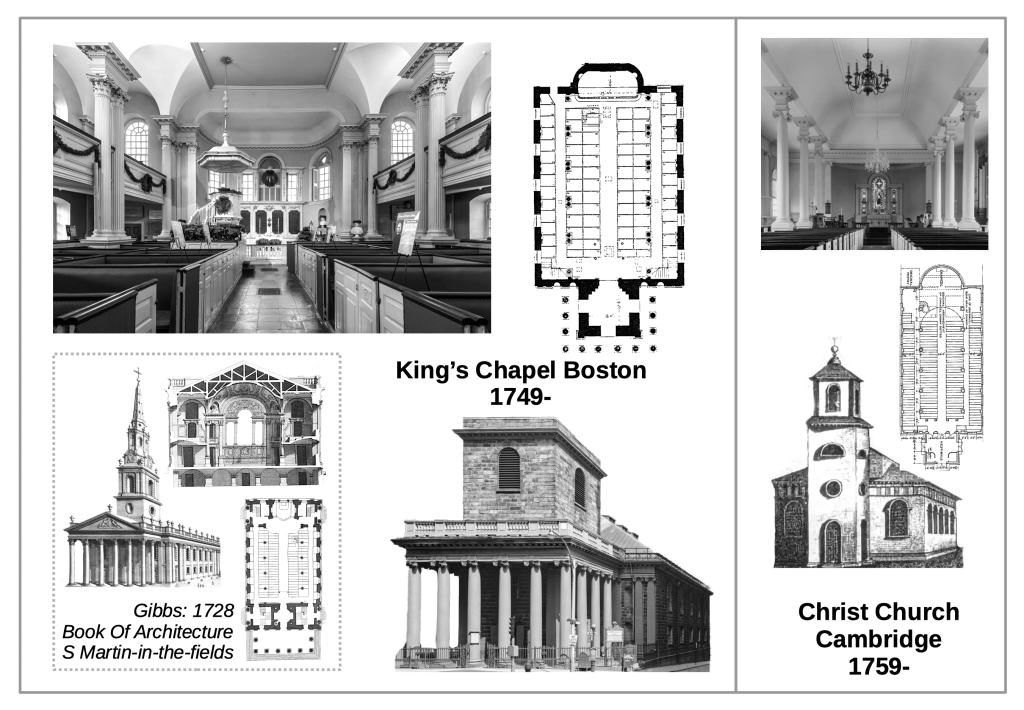

Drawings of James Gibb’s famous church of S. Martin-in-the-Fields in London were first published in 1728 and became an important influence on American church architecture. Peter Harrison attempted to build a modified version of S. Martin-in-the-Fields at King’s Chapel in Boston in 1749. Unfortunately, the spire was never completed, and the portico, which Harrison wanted built in stone, was instead built of wood. However, the interior was the finest that had been built in New England up to that point. It adheres to the basic plan of Old North, but its pairs of giant columns give the interior an added monumentality and unity.

Harrison also designed Christ Church in Cambridge in 1759, a modest but interesting structure, featuring a dramatic set of interior columns perched on high pedestals. Much of Christ Church’s unique character derives from the fact that its columns are far too elaborate for the relative modesty of the structure. Like King’s Chapel, Christ Church was left incomplete, without the tall spire Harrison intended for it. These deficiencies highlight the tension between New England’s growing artistic ambitions, and the technical and financial means available to meet those ambitions.

Late 18th c. Provincial Meeting House Types

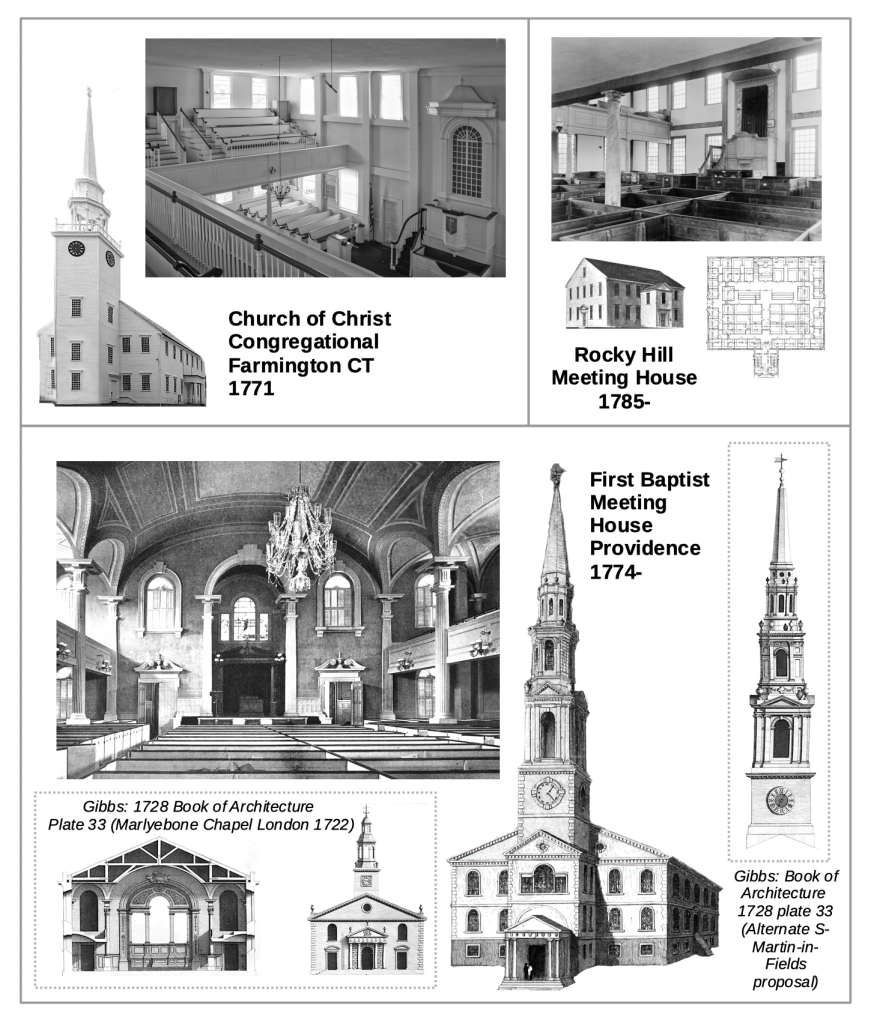

Outside of Boston, square meeting houses continued to be built throughout the 18th century. Architectural historian William Pierson categorizes these meeting houses into three basic types. The first type is represented by Rocky Hill Meeting House, built in 1785. Like its 17th century predecessors, it was built on a square plan without a spire, but adopts basic classical details including pediments, columns, dentils and wall panelling.

For congregations with more means, a tower could be added to the meeting house like the one at Old South Meeting House in Boston. A good representation of this type is the Congregational Church in Farmington Connecticut, built in 1771. Its octagonal tower was admired and copied at many other rural meeting houses.

The third type of meeting house is represented by the First Baptist Meeting House in Providence. At first glance, its interior looks more like an Anglican-style church than a traditional New England meeting house. However, it is much wider than a typical anglican church and is squarish in plan. Additionally, it has no central aisle, making an Anglican or Catholic processional unthinkable.

The architect of First Baptist borrowed heavily from James Gibb’s drawings of his Marylebone Church in London. Like Marylebone, First Baptist contains a classical portico flanked by paired columns. Its vaulting also takes its inspiration from Gibb’s drawing of Marylebone’s interior. The steeple, one of the finest in New England, was drawn directly from an alternative model Gibbs had designed for S. Martin-in-the Fields.

The Federal Style

Architectural historians generally classify pre-Revolutionary New England architecture as “Georgian,” and post Revolutionary architecture as “Federal.” However, the two styles are similar and sometimes hard to distinguish. The churches illustrated above are classified as Federal, but they look similar to those discussed earlier in this post.

There are however a few key architectural motifs that distinguish the Federal style from the Georgian. These motifs were borrowed from a prominent English architect named Robert Adam, whose drawings were published and widely studied in America. Adam’s architectural innovations include windows set within wall arches, fanlights over doors, and a feature called “Palladian-window-in-blind-arch.” Windows set in wall arches can be seen at Charles Street Meeting House and Center Church in New Haven. Fanlights are found over doors at Charles Street, Old Bennington, and Old Lyme. The Palladian-in-blind-arch motif can be seen over the pulpit at Center Church in New Haven.

Of the five churches illustrated in figure 3, architect Asher Benjamin designed three of them: Charles Street Meeting House, Old West Methodist, and the Center Church in New Haven. Benjamin also published popular architectural pattern books that were used throughout the 19th century. The church of Old Bennington in Vermont was based on one of Benjamin’s drawings.

Benjamin’s Center Church in New Haven of 1812 was based on Gibb’s S. Martin-in-the-Fields, but contained some subtle improvements in the overall proportions. S. Martin’s facade was essentially a classical Roman temple topped by a massive steeple, creating a somewhat incongruous and top-heavy effect. Center Church fixes this problem by creating three separate, receding planes in the church facade. The foremost plane of Center Church consists of the temple portico, which has been reduced in size, compared to S. Martin. Directly behind this plane, is the plane of tower, followed by the plane of the church itself. This three-tiered plane can also be seen in the facades at Old Bennington and Old Lyme. Thanks to this planar arrangement, each of these churches has a more pleasing sense of proportion than the unwieldy composition at S. Martin-in-the-fields.

Old Lyme’s First Congregationalist Church (1816-) is based on Benjamin’s Center Church, but was built in wood rather than brick. In terms of affordability and beauty of proportion, it is perhaps the finest church in New England. Its gabled pediment is echoed by the pediment of its portico. Compared to the lavish ornamentation at Center Church, Old Lyme’s ornamentation is restrained, almost severe, which is in keeping with the puritan heritage of its congregationalist community.

Thomas Bulfinch’s Neoclassicism and the Greek Revival

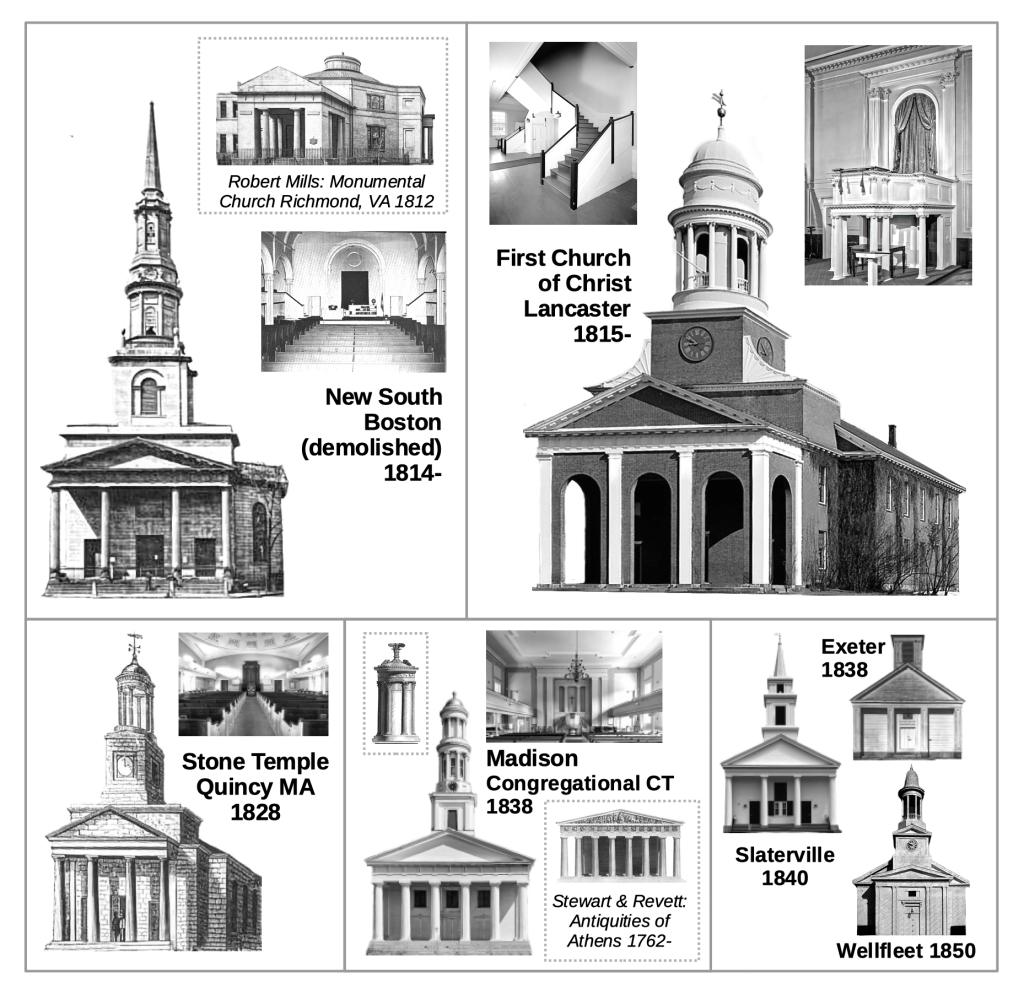

Architects in the early 19th century began experimenting with a monumental form of classicism sometimes called “neoclassical.” The Monumental Church in Richmond, built in 1812 is an extreme example of this type: an octagonal floor plan with no steeple. Its facade included massive side piers with broad flat planes and little ornamentation. New England was far too conservative for this sort of architecture, but Thomas Bulfinch’s New South Church of 1814 in Boston adopted aspects of the neoclassical style. Like the Monumental Church, it was built on an octagonal plan. It also contained a bold, sturdy platform upon which the spire was built. However, it retains a traditional federal-style front portico. Its thin, widely spaced columns look somewhat out of place with the bold architectural forms behind it.

Bulfinch’s church in Lancaster, designed a year later, represents a marked improvement on the New South design. Like New South, Lancaster’s steeple is placed on a massive platform housing an interior vestibule. However, unlike New South, Lancaster’s steeple is much shorter and thicker, and its brick portico is far more monumental, with bold brick arches replacing the traditional columns. The composition is tied neatly together with sloping “fans” connecting the vestibule to the steeple, a faint echo of Italian mannerist architecture which utilized similar motifs to unify church facades (see Il Gesu, Rome 1580). Lancaster’s interior is also noteworthy for the minimalist design of the vestibule’s staircase, anticipating both mid-19th century Shaker and early 20th century Bauhaus design.

The Stone Temple in Quincy of 1828 also builds on Bullfinch’s New South model, simplifying the steeple, lengthening the portico, and reducing the space between the columns, creating more pleasing set of proportions. The Stone Temple was also influenced by the emerging “Greek Revival,” inspired by archeological drawings that had been published in Stuart and Revett’s “Antiquities of Athens” from 1762. These publications were slowly disseminated in the United States in the early 19th century and provided an alternative, “democratic” heritage stemming from ancient Greece, as opposed to a classical tradition mediated through England and its monarchy.

One of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in New England is the Congregational Church in Madison, CT built in 1838. The architect made a careful study of the Athenian Parthenon for the portico, and modeled the steeple on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates. Additionally, the tower contains a decorative, tapered doorway inspired by a concurrent Egyptian Revival.

The Greek Revival also influenced provincial New England church architecture of the period. The examples shown from Exeter, Slatersville, and Wellfleet are not archeologically correct examples of ancient Greek architecture, but in their simple, bright clarity, they reflect the spirit of the style.

Colonial Revival

New England church architecture in the 18th century was shaped by the merger of the puritan meeting house plan with the Wren/Gibbs steeple style. During the course of the 19th century, this unique style gradually fell out of favor, replaced by a broader national obsession with Gothic and Romanesque Revivals. A Colonial Revival emerged in the latter half of the 19th century as post-Civil War Americans sought a unifying architectural style derived from the period of the republic’s founding. Additionally, the United States’ rapid industrialization had awakened nostalgia for simpler times. Initially the Colonial Revival was a domestic architectural phenomenon, but by the early 20th century, it was being used for civic and religious buildings as well.

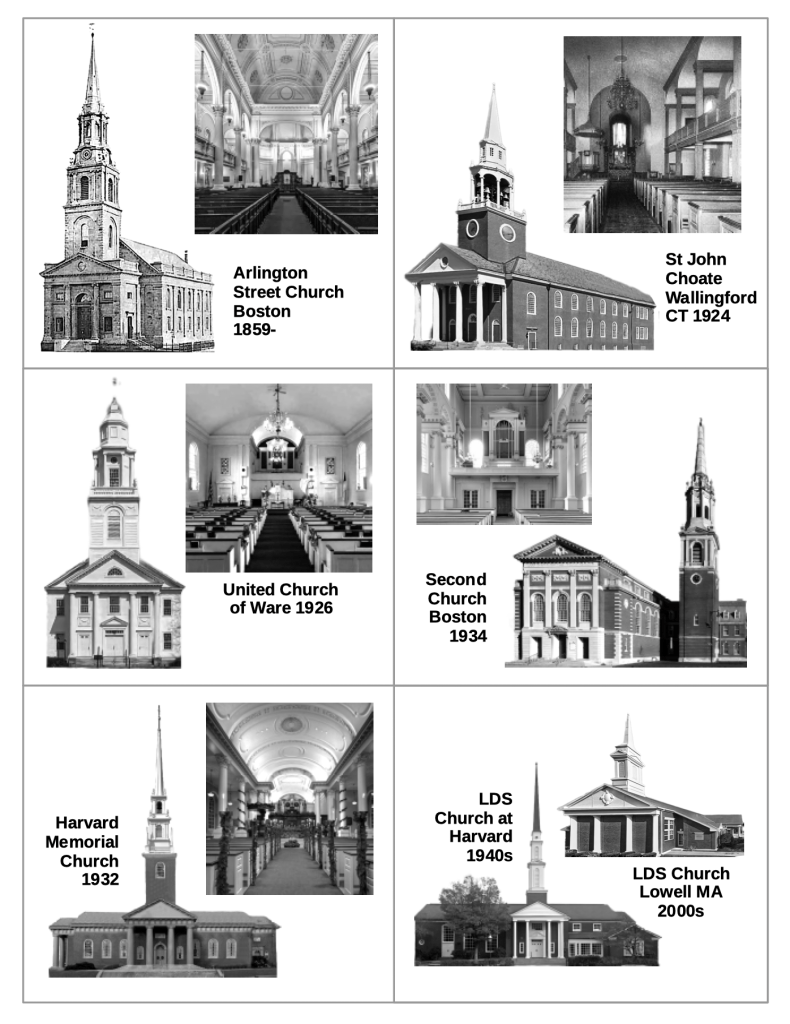

Boston’s Arlington Street Church of 1859 predates the Colonial Revival, but is nevertheless an important precursor. The architect Arthur Gilman worked in grand Victorian styles like “second empire,” but for Arlington Street Church he returned to the English Baroque of Wren and Gibbs. Additionally, the influence of the Greek Revival can be seen in the portico, which is built “in antis,” meaning that the columns in the center are framed by outer pilasters, a popular device in ancient Greek architecture. The interior diverges from Wren and Gibbs by including a columned arcade dividing the galleried aisles from the nave, which was more common in Gothic or Romanesque architecture.

Some of the finest Colonial Revival churches were built by Ralph Adams Cram and his associates. While Cram was primarily known for his Gothic Revival work, the church of S. John at Choate School shows his familiarity with Wren’s church of S. James Piccadilly with it’s barrel vaulted nave and transverse vaulted aisles (figure 1). The exterior was built in Asher Benjamin’s style, which was perfected at Center Church in New Haven (figure 4).

Philip H. Frohman, an associate of Cram, also turned to Asher Benjamin for inspiration in his United Church of Ware. He also included a set of giant attached columns framing the two floors of the facade, reflecting Palladian styles that had been popular in the American south during the colonial period.

Cram’s Second Church of Boston (now Ruggles Baptist Church) is an interesting hybrid. Its steeple is detached, a common arrangement in Italian medieval architecture. However the steeple itself is pure Wren/Gibbs. The facade also departs from the Colonial style, embracing Beaux Arts monumentality.

Harvard Memorial Church is built in the colonial style, but places the steeple in the center of the church, rather than the front, an arrangement usually reserved for gothic or romanesque crossing towers. The interior takes its cue from Peter Harrison’s Christ Church Cambridge (figure 2), with its massive Corinthian columns perched on high pedestals.

Apart from these important commissions, the Colonial Revival style remains popular choice for smaller, more modest churches like the hundreds of LDS chapels built across the United States. The LDS chapel at Harvard, built in the 1940s seems to have been inspired by the Harvard Memorial Chapel built a few years earlier. LDS chapels built in the 21st century also feature colonial motifs, like the one pictured from Lowell, MA. Mormonism’s founder Joseph Smith was born in Vermont, and the LDS church’s New England heritage has become an important aspect of its architectural identity.

Conclusion

As 21st century mainstream religious participation declines, there are fewer opportunities to build new churches. Growing evangelical congregations often prefer to meet in buildings that don’t look like churches, such as warehouses or arenas. Today, the challenge is the restoration and retention of existing churches. Understanding the historical development of the New England style is more important than ever as congregations and preservation groups struggle to raise money to keep the heritage alive. Thanks for reading.

Leave a reply to Nate Cancel reply